What to Know Today

How police violence contributes to community mistrust. A new working paper offers one potential contributing factor to the ongoing homicide surge: the decline in civilian reporting to — and engagement with — police after officer violence. In the eight cities the researchers surveyed, the number of 911 calls per gunshot (as detected by ShotSpotter) dropped by more than half in the week after George Floyd’s death in May 2020 — from 207 in the seven days before to less than 90 after. The significantly lower rates remained consistent through the rest of the year; declines were also consistent in Black, Hispanic, and white neighborhoods. Moreover, the authors found that that Derek Chauvin’s conviction for Floyd’s murder didn’t reverse the declines, indicating the difficulty of restoring community trust in law enforcement. “Our results suggest high-profile acts of police violence can inflict lasting damage to civilian trust, a key input into law enforcement’s ability to solve crimes and maintain public safety,” tweeted lead author Desmond Ang, an economist and assistant professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.

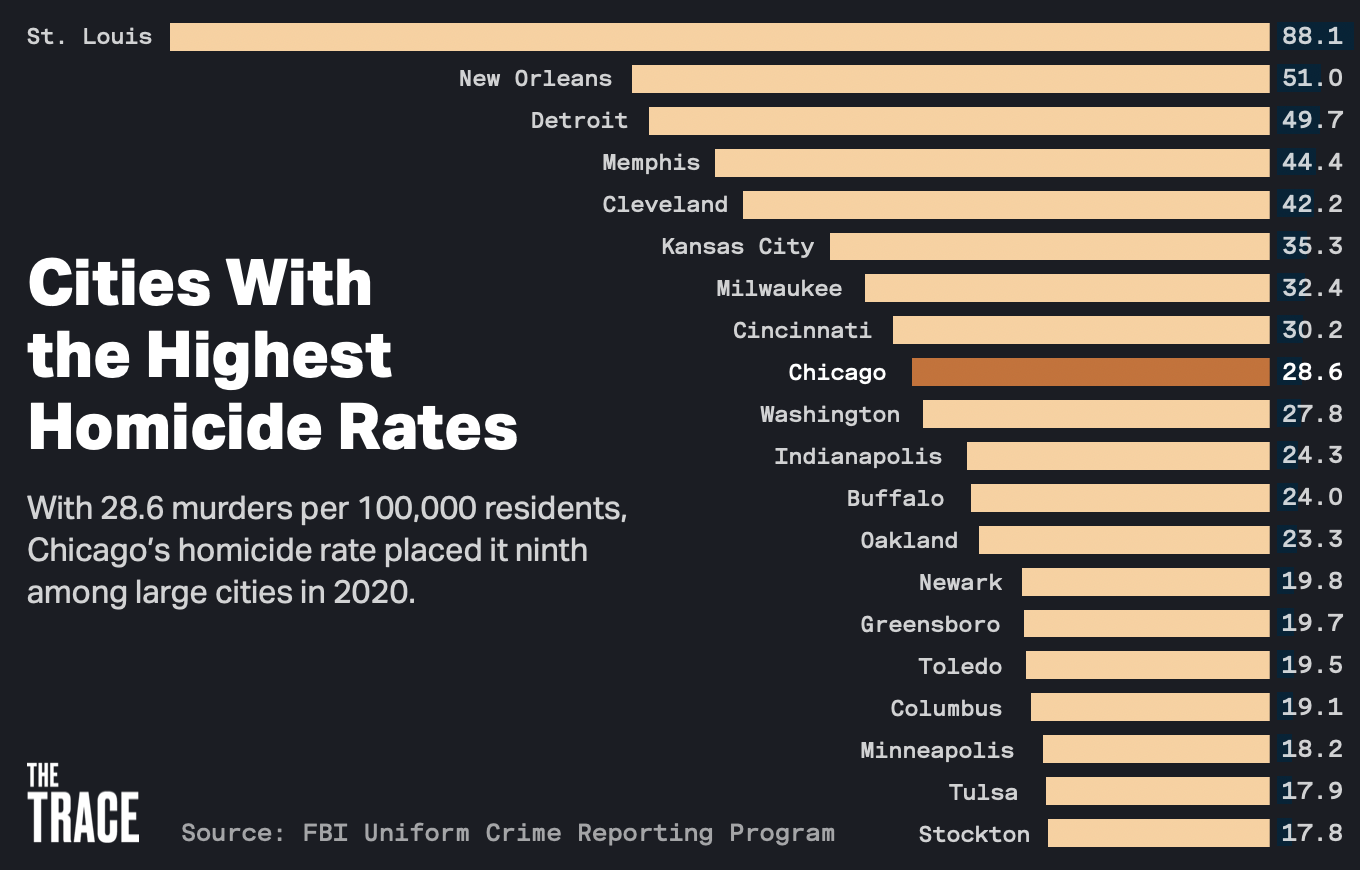

Murder rates in U.S. cities, ranked. Daniel Nass updated our 2018 article with the FBI’s final numbers for 2020. The long-term trend is clear: America is a much less murderous place than it once was. But it didn’t seem that way in 2020, when a wave of gun violence began in tandem with the coronavirus pandemic. The murder rate now stands at 6.4 murders per 100,000 people, the highest rate since 1998. In cities with more than 250,000 residents, the rate rose by 33 percent to 12.8 — a level not seen since 2006.

“It feels like we’re losing ground”: A murder crisis in the Bay Area. Homicides rose in nine out of 12 counties that constituted the greater San Francisco Bay Area in 2020, according to an analysis by The Guardian. That amounted to a 25 percent rise overall and 114 more homicides than in 2019. But the rise was not evenly distributed, with Oakland, Vallejo, and Stockton bearing the brunt, while the more affluent and suburban regions were largely unscathed. As happened nationwide, the vast majority of victims were Black and Hispanic. The surge came after more than a decade of large and steady declines in gun violence. “It feels like we’re losing ground,” said Sonya Mitchell, whose son was fatally shot last year.

Capital Gazette shooter sentenced to six consecutive life terms. The perpetrator of the attack previously pleaded guilty to the 2018 mass shooting that took the lives of five employees of the newspaper — Gerald Fischman, Rob Hiaasen, John McNamara, Rebecca Smith and Wendi Winters. “The impact of this case is simply immense,” the judge said before he handed out the sentence. “To say the defendant showed a callous and cruel disregard for the sanctity of human life is simply an understatement.”

How gentrification exacerbates gun violence. A new working paper from Zachary Porreca, a professor of economics at West Virginia University, posits that as gentrification reduces the viable space for the illegal drug market, it prompts more turf wars and more violence. In Philadelphia, he finds that 21 percent of shootings in the last decade — 5,800 incidents in total — were the result of this process. Moreover, he finds that link is greatly magnified when a high drug crime block is gentrifying.

Data Point

45 percent — the number of unhoused and unstably housed women who had been attacked with a firearm as an adult, according to a study of such women in San Francisco. The survey, which also looked at a history of violence during childhood, found that women who had been injured by kicking or hitting when they were young were 70 percent more likely to be attacked with a gun as an adult. [Injury Epidemiology]