Devon Little was shot for the first time as he was heading home from a cookout in West Baltimore.

The assault happened around midnight in June of 2015. It wasn’t until sunrise that a security guard stumbled across him in a deserted parking lot. Little’s cellphone was gone, he would later say, along with his brand-new Nikes and the gold fronts from his teeth. Blood pooled from wounds to his head and shoulder as he lay splayed on the pavement in his white socks.

Little, then 25, woke from a coma in a hospital a week later with a bullet fragment still lodged behind his left sinus. Doctors had temporarily removed part of his skull to relieve pressure on his brain caused by the swelling.

He had survived the shooting. But his exposure to the lawless violence that ravages swaths of cities across America was not over.

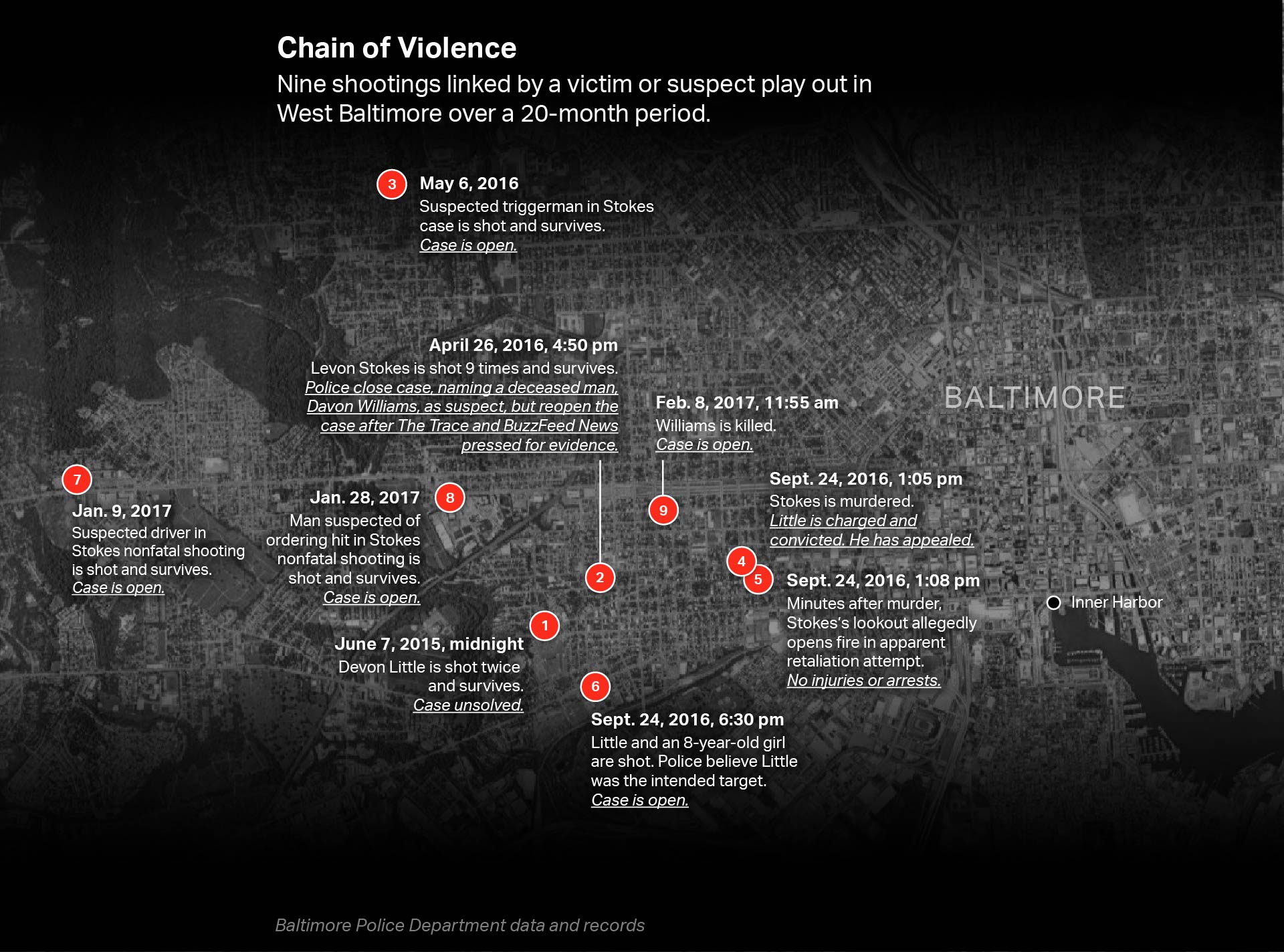

Discharged from the hospital badly injured and with his shooter still at large, Little became part of a cluster of nine shootings, all linked by a shared victim or suspect, that would leave at least seven victims over the next 20 months, some of them shot multiple times. Among the wounded was an 8-year-old girl, hit in the crossfire as she played in the street. A toddler narrowly escaped becoming another casualty; her grandmother found a bullet in her shoe.

As the spiral intensified, Little would be shot a second time. He would also become the only person arrested and prosecuted for any one of the shootings — a conviction he is appealing, insisting that he was railroaded by detectives’ perfunctory investigation. Another shooting in the string was quietly closed by naming a dead man as the perpetrator — then reopened after The Trace and BuzzFeed News pressed the Baltimore police for the supporting evidence.

The spate of Baltimore shootings illustrates a deadly problem in cities across the country: Systemic failure to solve gun crimes fuels widening cycles of violence, leaving shooters free to strike again, eroding trust in the police, and driving some victims to seek their own justice.

A yearlong investigation by The Trace and BuzzFeed News, based on data obtained from 22 cities, has found that:

- In cities from coast to coast, the odds that police will solve a shooting are abysmally low and dropping. Homicides and assaults carried out with guns lead to arrests about half as often as when the same crimes are committed using other weapons or physical force.

- The odds of an arrest are particularly low when victims survive, in part because those crimes tend to be assigned to detectives whose caseloads are exponentially higher compared to their colleagues in the homicide department, who are often overburdened themselves.

- The chances are even lower if the victims, like Little, are people of color. When a black or Hispanic person is fatally shot, the likelihood that local detectives will catch the culprit is 35 percent — 18 percentage points fewer than when the victim is white. For gun assaults, the arrest rate is 21 percent if the victim is black or Hispanic, versus 37 percent for white victims.

By failing to solve so many shootings, police are “missing a potential opportunity to stop cascades of gun violence,” said Andrew Papachristos, a professor of sociology at Northwestern University.

Over the past three decades, the percentage of shooters who escape justice has soared — even as the nation’s overall violent crime rate has plummeted and advances in forensic technology have given investigators powerful new tools.

The crisis of unsolved shootings isn’t confined to cash-strapped cities like Baltimore, but also hits some of America’s most affluent metropolises. In 2016, Los Angeles made arrests for just 17 percent of gun assaults, and Chicago for less than 12 percent. The same year, San Francisco managed to make arrests in just 15 percent of the city’s nonfatal shootings. In Boston, the figure was just 10 percent.

A case is closed, or cleared, when a suspect is arrested, or, for reasons beyond the police department’s control, cannot be arrested. The lower the clearance rate, the higher the number of shooters walking the streets who have gotten away with their crime.

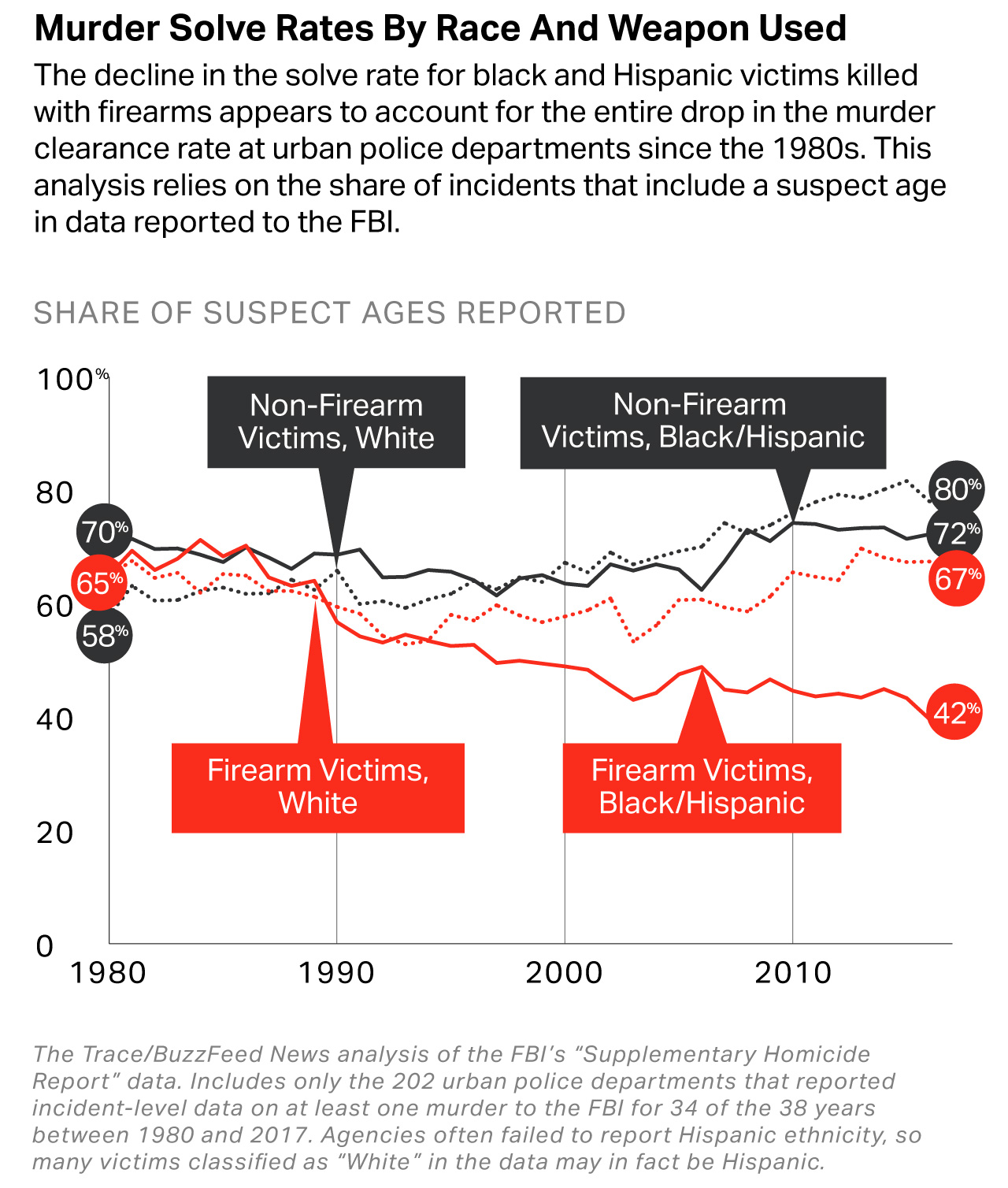

The burden of unsolved shootings falls disproportionately on minority communities. Eighty percent of gun murder victims in American cities are black or Hispanic. (Government agencies often use “Hispanic” in statistical breakdowns, though in many cases “Latino” may be more accurate.) A drop of more than 20 points in the solve rate for these victims appears to account for the entire decline in murder clearance rates since the 1980s, according to an exclusive analysis of FBI data by The Trace and BuzzFeed News.

“They don’t go after the murderers in the cities, the ones that kill our sons,” said Daphne Alston, founder of the Baltimore group Mothers of Murdered Sons and Daughters United, and whose own son’s murder has gone unsolved for more than a decade. “People have no hope. They feel like the police don’t love them; they feel like they’re nothing to nobody because they’re a young black male in trouble in the street.”

There’s no analogous historical data available for nonfatal shootings, but present-day data collected from individual cities suggest that those cases are also solved at lower rates when the victim is black or Hispanic.

Police say they investigate all cases with equal vigor, and are often hindered by external factors, such as witnesses and victims who refuse to talk — out of fear of retaliation, to hide their own criminal activity, or because of a distrust in law enforcement. But members of black and Hispanic communities in cities across the country have said detectives don’t seem to work as hard for them.

Three former top officials with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division told The Trace and BuzzFeed News that officials have frequently heard such complaints when they assessed allegations of racially biased policing. The perception itself often makes the community less willing to share information with the police, several of the division’s reports have noted.

Angela Brown, a longtime Baltimorean, said it’s no wonder witnesses don’t talk to detectives. “Mind your own business, and stay alive,” she said, speaking from her front porch, not far from the spot where a few months earlier two women had been shot, one fatally. “The police aren’t going to do nothing about it anyway, so why should I say anything?”

Beneath the systemic failure to solve gun crime is a lack of police resources. Nonfatal shootings are at least as difficult to investigate as fatal ones, detectives say, yet across the country, city leaders invest far less in solving them. In 2017, Baltimore had 57 homicide detectives assigned to 483 cases. The Citywide Shooting Unit had just 26 detectives for 703 cases, according to a recent staffing report.

Some police departments are so understaffed that a large share of shooting cases receive only a cursory effort, or don’t get passed to a detective at all. In Oakland’s Felony Assault Unit, more than 40 percent of cases were not assigned to an investigator in 2017. Portland, Oregon, did not assign 38 percent of its felony assaults that year.

In Flint, Michigan, a 2013 audit found just 14 detectives were each juggling an average of 927 cases, including homicides and other violent crimes, a number, auditors wrote, that was “almost beyond comprehension.” A spokesperson declined to release current caseloads, citing “safety reasons.”

In Houston, the police department cut detectives even after auditors warned in 2014 that an “excessively high” number of cases with workable leads were not being investigated. This included more than 3,000 serious assaults in the previous year alone.

But the department was also under pressure to improve response times to 911 calls, said then-police chief Charles McClelland in March 2018. In 2016, under an interim chief, the department actually cut its investigative capacity by redeploying 70 detectives to work patrol. The city’s closure rate for gun assaults tumbled from 20 percent that year to a meager 9 percent during the first half of 2018. Houston has recently quadrupled the number of detectives handling nonfatal shootings.

The effect of understaffing detective divisions is shifting the burden of solving shootings from police to victims. In cases “where the person said, ‘Well I don’t know who shot me,’ well then we would just send them a letter stating, ‘If you would like, if you have other evidence or more information, you can contact us for an investigation,’” said Lieutenant Ed Siska of the Houston Police Department’s Major Assaults Unit.

“If the victim wouldn’t cooperate, even if we had some leads, we would suspend the case.”

Detectives working outsize caseloads must move on if leads don’t come together quickly enough. And that sends a message to the small networks of people where a disproportionate share of gun violence plays out. In Chicago, a 2018 study found just 10 percent of young adults in high-violence neighborhoods who have carried a gun believed they would get caught if they shot at someone.

The problem is starkly illustrated in Baltimore, where neighborhoods already disadvantaged by extreme poverty and disinvestment are scarred by extraordinary levels of violence.

The Trace and BuzzFeed News analyzed nearly 3,500 shootings — both fatal and nonfatal — recorded in Baltimore from 2012 to mid-2017. The results showed how violence ripped through the community, fueled by a failure by the city to hold shooters accountable.

More than 200 people who were named as a victim in one case were also named as a suspect in another. More than 170 people were shot, as Little was, on more than one occasion. And 87 people were listed as suspects in more than one shooting, including one man believed to have been involved in eight shootings that left nine people dead and three wounded before he was finally arrested in 2016.

By analyzing both the Baltimore Police database and internal police records, The Trace and BuzzFeed News were able to identify the shooting of Devon Little as the first in a series of nine gun assaults and homicides — connecting the dots between victims who went on to be shot again or to become suspects in other crimes, or suspects who were later shot themselves.

The analysis itself reveals the shortcomings of the city’s efforts to catch those responsible for gun crime.

Altogether, The Trace and BuzzFeed News linked 826 of the shootings in the Baltimore Police database to at least one other shooting through a shared victim or suspect. But the true number of connected cases is certainly much higher — just one-third of the shootings in the database name a suspect.

Only five of the shootings in the series that started with Little are connected in the city’s database. The Trace and BuzzFeed News linked another four by studying detective case files and court transcripts. Because those records were only available for the two cases that police managed to close, it’s possible that the string of shootings is even larger.

All of the victims in the series of shootings, like the vast majority of gun violence victims in Baltimore, are black. The police department believes some of the shootings had connections to the Black Guerilla Family gang, whose terrorizing hold on many neighborhoods in West Baltimore has made witnesses reluctant to talk to police. In other cases, witnesses who have cooperated have been murdered in broad daylight or had their houses firebombed.

While the detectives investigating this cluster of Baltimore shootings confronted unique local challenges, the cases illustrate many of the problems facing cities around the country. Investigators were stretched so thin that they were frequently ineffective. Promising leads weren’t followed. And each unsolved gun crime had devastating ramifications for the families affected, even as it escaped attention from the public at large.

Little’s recovery was rocky. Medical records show he had severe migraines, seizures, memory loss, and difficulty controlling his movements. He began to make mistakes at his job with Meals on Wheels and had trouble keeping track of his daughter’s school schedule. He told The Trace and BuzzFeed News that he also used street drugs, such as marijuana and pain pills, to tame his headaches.

In the absence of answers from police, Little began investigating his own case. He roamed his neighborhood in a daze, he says, with his feeding tube tied off with a knot and his hat cocked sideways, revealing his now-lopsided skull, asking people if they knew who had shot him.

He feared the answer was common knowledge. But nobody would tell him.

He grew increasingly paranoid. The shooter could be anywhere. Every smile seemed potentially sinister. He started crossing the street to avoid groups of people.

If Little had died, his case would have been assigned to one of Baltimore’s homicide detectives, who generally get around eight cases per year — nearly triple the optimal caseload for a homicide unit, which needs the bandwidth to painstakingly comb through intelligence and canvass the streets for evidence and witnesses.

Because Little lived, his case was assigned to Jimmy Dease, a general assignment detective who worked out of the Southwestern patrol district, one of the most violent in the city. Dease picked up a new case nearly every day.

Such a workload, The Trace and BuzzFeed News found, is one reason greater and greater shares of shooters are getting away with their crimes.

What’s more, the new technologies that have given police departments more tools for generating leads have paradoxically increased the strain on detectives. Advances in forensics have made it easier to link suspects to crimes through DNA or ballistics evidence. Troves of data from cellphone records, license plate readers and surveillance cameras can plot movements, and social media posts can reveal connections among individuals. But all that machine-generated intel takes time to sift through and must still be confirmed by officers putting in shoe-leather detective work.

Baltimore actually puts more detectives on nonfatal shootings than many other big cities. “We work every case,” said the head of the city’s Criminal Investigation Division, Byron Conaway. But those cases come at a relentless pace.

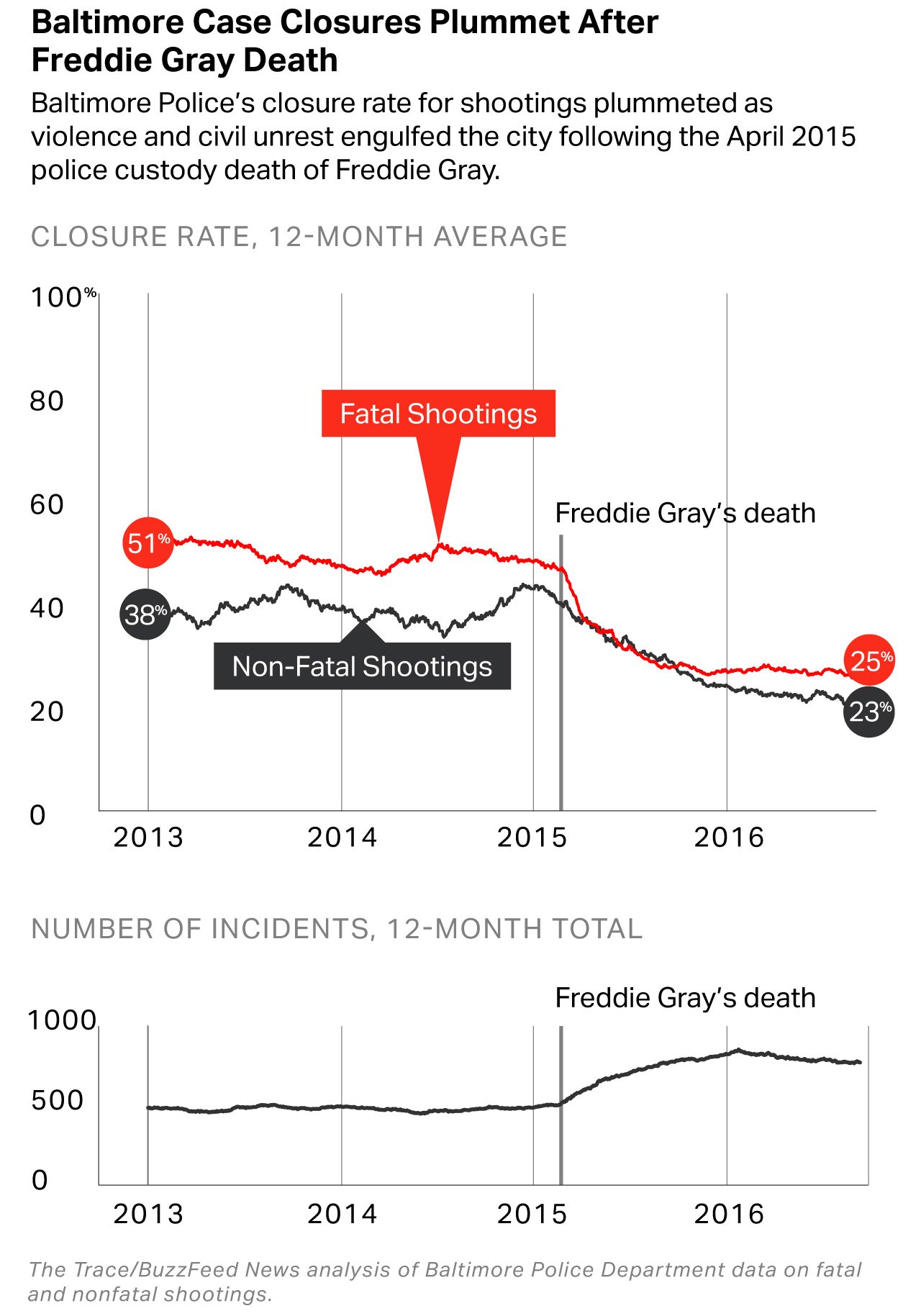

The investigation into who had shot Little commenced as Baltimore detectives found themselves strained past their breaking point. In April 2015, two months before Little’s shooting, Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black man, had died after officers gave him a “rough ride” in a police van. In reaction, Baltimore plunged into the city’s worst riots since the 1960s. Over the next 12 months, shootings skyrocketed by 68 percent, overwhelming detectives.

Instead of getting backup, detectives were pulled from their cases, sometimes for days at a time, to help quell the violence. By 2016, homicide investigators cumulatively spent 10,000 hours working riot duty and patrol rather than tracking down murderers, according to Conaway. The Citywide Shooting Unit, created that year to centralize investigations of nonfatal cases, did not keep a similar count, but “they were out there” too, Conaway said.

“To be blunt, they were crippled,” a former homicide detective, Vernon Parker, said.

In the ensuing months, Baltimore’s closure rate for shootings dropped to 25 percent, the lowest in recent history. More than 1,100 cases from 2015 and 2016 alone remained unsolved by the following summer.

After Little got out of the hospital, Dease, the detective, dropped by his mother’s house a few times to see if Little or his family had any information on who might have shot him.

The parking lot where the security guard found Little is lined by strip malls, but many of the nearby homes stand vacant. Police could not identify anyone who said they saw the shooting, and though investigators found a few people who said they had heard screams, no one went to his aid. That left Little himself as the last potential witness.

But Little had no idea. “Me turning around was like the last minute of my memory,” he said, recalling the moment right before he was shot.

Little wasn’t known on the streets, a Baltimore Police source said, so the other sources of intelligence — tapped jailhouse calls, “word on the street,” interrogations of the recently arrested — came up empty.

Baltimore Police denied a request to let reporters review the case file, saying the investigation remains open. Without those records, it’s impossible to know how thoroughly Dease and other detectives worked to find the shooter before the investigation tailed off.

Little’s mother, Janice Moses, said she followed up several times, suggesting leads, hopeful for a break in her son’s case. “But they didn’t do anything,” she said. “I guess they were looking at me saying, ‘You have your son back.’”

Moses feared her son’s own makeshift investigation, in which he walked the streets asking people if they knew who shot him, would get him killed. She pleaded with him: “Devon, please stop. Please. Please Devon, please stop doing that.”

“But he just kept trying,” she said, “to figure out why somebody would shoot him.”

In contrast to Little’s case, the shooting of Levon Stokes 10 months later generated, as one detective put it, “tremendous leads.”

But police didn’t do much with them.

Stokes, 25, was a street-level drug dealer and father of two. He was walking down a narrow alleyway lined by boarded-up row houses in West Baltimore that had been a haven for drug sales for generations when a silver Honda Accord pulled up. It was about 5 p.m. on April 26, 2016.

The passenger door of the Honda cracked open. Someone inside raised a gun. Stokes tried to run, but a bullet pierced his back and he crumpled to the ground. As he tried to crawl away, the gunman shot him eight more times.

In the following days, while Stokes lay intubated and unable to speak at the University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore Police detectives Erin Masters and Theodore Sebekos got multiple breaks in the case.

Through another drug dealer, the detectives got the name of someone who was said to have pulled the trigger, as well as the man who allegedly ordered the hit over “50 pills of dope” — around $500 worth of heroin — according to the notes in the case file.

Police often complain that victims involved in the drug trade refuse to cooperate in investigations. “We have individuals here in Baltimore that don’t want to talk to police, and they don’t want to tell us who shot them,” said Conaway, the Criminal Investigation Division boss.

But after Stokes was able to speak again, he shared some information with Masters and Sebekos during a visit to his hospital room. According to the detectives’ notes, Stokes said he wasn’t able to see who had shot him behind the car’s tinted windows. But he did give the detectives information that helped identify a third potential suspect, the owner of the car, describing him as a “fat, tall, light-skinned male who wears glasses.”

On May 10, 2016, two weeks after the shooting, a sergeant emailed Masters, the lead detective on the case, the name of the Honda’s owner. The investigation into who had tried to kill Stokes looked to be gaining momentum.

Instead, it ground to a halt.

The identification of the Honda’s owner was the last entry in the detectives’ activity log for the rest of the year.

Photo lineups that include the alleged driver and gunman are stuffed into the case file. But the signature lines are empty, indicating that the detectives never showed them to Stokes.

In fact, the 284-page case file, obtained by The Trace and BuzzFeed News, indicates no further attempt, over the next eight months, to interview the three suspects, or potential witnesses, or informants — or to seek more information from Stokes himself.

Baltimore Police officials would not say why Masters failed to follow up on the leads in Stokes’s case. But detectives interviewed by The Trace and BuzzFeed News, most on the condition of anonymity to protect their jobs, all had the same theory: too high a caseload.

“The case volume is mind-boggling,” said former Baltimore homicide detective Gordon Carew, who left the department in 2016 after 27 years in homicide. “You get so many cases and you triage them. You move forward with your most viable case, you pour all your energy into that, and you try and keep your head above water on everything else.”

As the investigation into his shooting idled, Stokes stayed at his mother’s house on the north side of town, slowly recovering from his nine bullet wounds. For his protection, his family let on that he was dead.

Soon, he would be. And Little, still waiting for his own assailant to be apprehended, would be blamed for the killing.

Stokes had been afraid to return to his old turf in West Baltimore. But he felt he had to, said James Arthur Graves Jr., whose family owns the house where Stokes’s mother lived: Stokes’s girlfriend needed help with their two kids. Graves said he helped Stokes into the car the day he left, “you know, because he couldn’t walk.

“I think he died the next week,” he said.

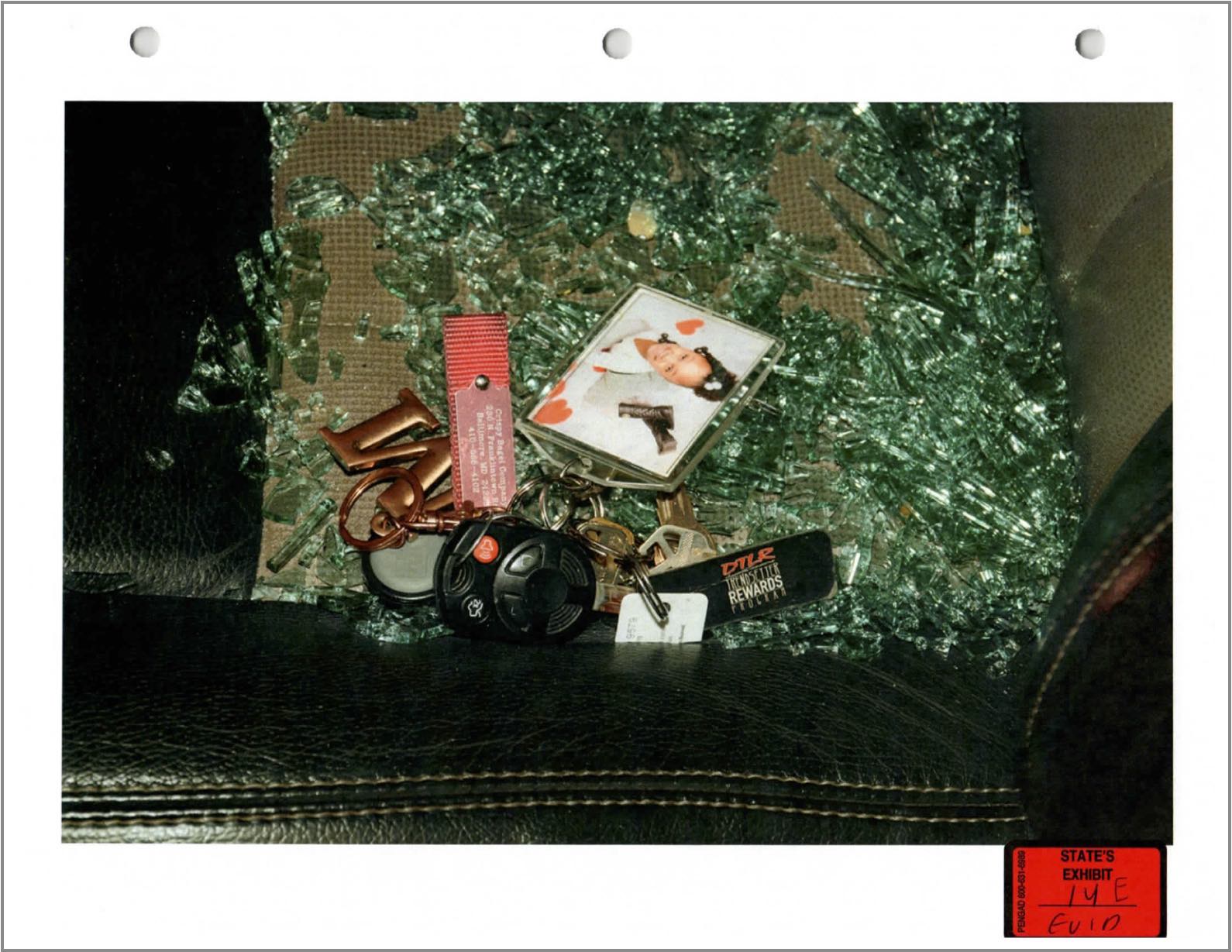

On the afternoon of September 24, 2016, Stokes was sitting in the driver’s seat of his girlfriend’s Mercury, parked in front of a strip of brick row houses on South Carey Street, a little more than a mile and a half from Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and its throngs of tourists. Dangling from his key chain was a photo of his 5-year-old daughter. His infant son’s car seat was strapped into the back seat.

He was there to sell drugs, his mother, Tonia Cox, later testified in court. His friend, Ritchie Hicks, sat on a stoop beside the car, acting as a lookout.

Around 1 p.m., Tonia and her teenage daughter, Tierra Cox, said they dropped by the spot to say hello, and they all chatted through the passenger-side window.

As his family stood by, Stokes started shouting back and forth with a man wearing a black hooded sweatshirt standing in the alleyway across the street.

“Whatever he was doing made my brother mad,” Stokes’s sister said. Stokes called out to the man, his sister recalled, saying, “They’ll blow your head off.”

The man in the hoodie walked up to the car, stared Stokes’s mother and sister in the eyes, then whipped out a gun and pulled the trigger, they testified.

Stokes was struck three times, in the head, neck, and abdomen. When police arrived at the scene, they had to pull Tonia Cox off her son’s body as she begged him not to die. “He passed right there in my face,” she said. “His eyes went in his head and he let go with his hands.”

Stokes’s murder was followed by a cascade of gunfire on the streets of West Baltimore that wounded a young child and put untold numbers of bystanders at risk.

As Stokes bled to death in his mother’s arms, surveillance cameras recorded two men running down the street.

One of them was carrying a gun. The authorities later said they believed it was Stokes’s friend Hicks, who had been keeping watch. The other man, authorities believe, was Stokes’s brother, Latrell Cox. As the two men tore around the corner on to South Carrollton Avenue, police said Hicks began blasting away, leaving seven shell casings on the street and sending a bullet through the window of an occupied row home. (Attempts to reach Hicks for this story were unsuccessful.)

The violence continued to ripple outward. Five hours after Stokes’s murder and about a mile away, Little was standing outside the Starlight Grocery Store on the corner of Wilkens Avenue and South Smallwood Street.

Suddenly, someone started shooting, unloading at least 13 rounds.

As Little ran, he said he saw “bullets going through cars.” One grazed him on the shoulder, causing him to fall. “I instantly did a push-up and ran as fast as I could,” he said.

A second round nearly hit a toddler playing on the sidewalk, according to a relative, somehow depositing a bullet in her shoe.

A third struck the foot of an 8-year-old girl named Jezell Savoy, who was Hula-Hooping with her friends. Her mother, Yolanda Savoy, told police she heard gunshots from inside her home. Then her daughter came running through the front door, crying.

Police noted a small, bloody sandal near the entrance of the home, and the child’s blood in and around the bathtub, where family members had tended to her wound as they waited for paramedics to arrive.

Jezell, now 11, saw a therapist for a year after she was shot, her mother said, adding that the child still sometimes blames herself for her injury, saying, “I shouldn’t have been down the streets.”

Little, meanwhile, got himself to the hospital, shot for the second time in 15 months. He said he again had no idea why, or by whom.

The wounded weren’t the only victims that day. All three shootings, like the vast majority of shootings in Baltimore, happened outside, for the entire community to witness. The experience of fleeing from gunfire, or navigating around bloodied bodies on the sidewalk, inflicts emotional trauma akin to what soldiers experience in war zones. In a review of more than 100 studies on the psychological impacts of living in a community with high violent crime rates, a group of academics found those who had only heard about violence in their community were just as likely to experience symptoms of PTSD as those who had directly witnessed it.

Kids are at particular risk. “Children who are exposed to violence are at higher risk for fear, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance, and of course are more likely to have difficulty in school. They’re more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol, more likely to engage in criminal activities,” said Katherine Hoops, a critical-care pediatrician at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

“The effect of violence is incredibly far-reaching.”

The Baltimore Police assigned the investigation of Stokes’s murder to homicide Detective Hassan Rasheed.

Rasheed and his partner pulled up to South Carey Street about 45 minutes after the shooting. More than a dozen officers and crime scene technicians were already there gathering and cataloging evidence. Stokes’s distraught mother, Tonia Cox, was speaking with one of them.

Rasheed noticed a security camera behind a clothing store that was pointed toward the block where Stokes was shot. He watched the video, which showed Stokes’s mother running from the scene. Then Rasheed walked over to the next block, where police believe Stokes’s lookout had attempted to avenge his killing, unleashing a barrage of shots on a busy street.

A car accident had just occurred at the same intersection, which was crowded with onlookers. Rasheed would later testify that he did not ask any of them whether they had glimpsed Stokes’s killer or the two men chasing him.

Over the next 24 hours, Rasheed reviewed footage from seven cameras surrounding the two scenes. None of it provided a clear image of the killer, he said.

That afternoon, Rasheed got an email from an officer on the Citywide Shooting Unit. The email relayed information from the mother of the young girl who had been shot in the foot.

“Just an fyi. Our juvenile victim’s mother is hearing that this shooting is stemming from an argument that ensued on the corner about something that happened earlier that day on Balto & Carey, and your homicide was that day.”

Baltimore Police had identified Little as the intended target of the shooting that hit the young girl — and that turned him into the lead suspect in Stokes’s death.

A week later, after Stokes’s funeral, Rasheed brought Stokes’s mother and sister to the homicide unit, where he showed them a photo array. Both picked Little from the lineup.

“That’s my brother’s homeboy. He shot my brother,” Tierra Cox said, crying, as she pointed to Little’s photograph, according to the detectives’ case file, obtained by The Trace and BuzzFeed News. Both women said they had never seen Little before. But they assumed that Stokes had known him, based on the way he spoke with the shooter before he was killed.

Little was arrested, charged, and convicted of murder. Placed in a maximum-security facility in the Appalachian foothills, about 140 miles from Baltimore, to serve his life sentence, he said a visit by The Trace and BuzzFeed News in July was his first since he was transferred there four months earlier.

Research has found that the most significant factors in clearing cases are witnesses and evidence of a motive. So it was with the prosecution of Little, which was built entirely on the testimony of Stokes’s mother, sister, and a third witness, a friend who said she glimpsed the side of the killer’s face as he stood over the victim, shooting.

Little’s appeal, dated July 2018, argued that the prosecution failed to tell his defense team the name and whereabouts of a fourth witness — Ritchie Hicks, the lookout who authorities believe was sitting on a stoop just a few feet away from Stokes when he was murdered, then minutes later indiscriminately unleashed a fusillade of bullets on a crowded street in a failed attempt to retaliate.

Months before the trial, Rasheed had made a half-hearted attempt to question Hicks when the two crossed paths at Central Booking and Intake Center, where Hicks was being held in connection with a different crime. Hicks walked past him, saying, “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” the detective would testify.

“That was the extent of the conversation.”

The appeal also noted that the prosecution didn’t bother to bring in Stokes’s brother, Latrell Cox. (Cox told The Trace and BuzzFeed News that he doesn’t know about any of the shootings that day, and denied knowing Ritchie Hicks.) Nor did police find any physical evidence implicating Little in the murder.

Little’s fingerprints were not among the three sets lifted from the vehicle where Stokes sat when he was shot at close range, according to documents in the case file. Three bullet casings left behind by the killer showed no links to Little, though ballistics comparisons did show that the same gun was used in two more shootings after Little was behind bars. That fact alone does not prove Little’s innocence, said Brian Harris, a retired Houston homicide detective who now instructs law enforcement agencies on investigative techniques. “But it would be a huge red flag.”

Cellphone records, which may have triangulated Little’s location at the time of the murder or shown communication between the two men, were not pulled, Rasheed said, because Little and his mother “would not confirm numbers.”

Nor did a police network analysis turn up any connections between Stokes and Little, whose name does not appear in the Baltimore Police Department’s database of suspected gang members.

The Trace and BuzzFeed News found no indication in the 837-page case file that detectives looked at or eliminated any other potential suspects.

Harris, who reviewed the documents for The Trace and BuzzFeed News, said it seems like the detective was in a rush to close the investigation: “Too many questions are left unanswered.”

On January 24, 2017, four months after Stokes was murdered, Masters and Sebekos, the team handling Stokes’s first, unsolved shooting, learned of a new development: The owner of the Honda allegedly involved in that attempted murder had been shot, too.

Sebekos visited the Honda owner at the Southwestern District station house. Sebekos asked him if he knew anything about the first shooting of Stokes, or his subsequent murder. The man said he did not. Then Sebekos asked him if he knew anything about a “drug beef” in the neighborhood. Again, the man said he had nothing to offer.

“No further intel was gained as a result of this interview,” Sebekos wrote.

The next entry in the detective file, seven days later, was a request for a ballistics analysis on the two shootings of Stokes and yet another violent gun crime now potentially connected to the case.

A second suspect in the case, the man accused of ordering the hit on Stokes over a drug dealing dispute, had been shot, as well. His name was Rondell Finch, and he was struck on a residential street near the city’s Western Cemetery, less than a mile from the earlier incident.

The ballistics test, which did not produce any matches, was the final entry in the activity log for the case.

In response to written questions, the Baltimore Police did not explain why Finch was never questioned. When reached by phone, Masters, the lead detective on the investigation, said, “I’m sorry, I have no comment to make. Goodbye,” and hung up.

Finch, who is now serving 27 years in prison for selling heroin, did not respond to an interview request.

The third and final suspect, the accused triggerman was also the victim of a subsequent shooting. Just a week after the attempt on Stokes’s life, he was struck in the tree-lined Walbrook neighborhood. But Masters never noted the incident in her case file. The Trace and BuzzFeed News found it in data obtained from the department.

Sometime later in 2017, Masters closed the book on Stokes’s first shooting, declaring the case “exceptionally cleared.”

That’s supposed to mean that the Baltimore Police had enough evidence to arrest the suspect, but couldn’t for reasons beyond the agency’s control.

Masters had determined that a man named Davon Williams was responsible for the attempt on Stokes’s life.

Williams could not be arrested because he, too, had since been shot to death. He was killed on February 8, 2017, just before noon, as he walked down the sidewalk with a group of men.

It is unclear how Masters zeroed in on Williams, whose name appears nowhere in the lengthy file on the first shooting of Stokes. Under Baltimore Police policy, when a detective makes an exceptional clearance, a report justifying that conclusion is forwarded to a supervisor, and then the unit commander, who must sign off on it.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

No such report was included in the case file given to The Trace and BuzzFeed News, and Baltimore Police denied repeated requests to turn it over.

Initially, Conaway defended the clearance, but also refused to say how Williams became the suspect. “I know exactly how it was closed,” he said, “but I would be giving up information that would put my witness in danger.”

After repeated questions from The Trace and BuzzFeed News, Matthew Jablow, chief of communications for the Baltimore Police, said in September that the department had reopened the case. “We’re not comfortable now” with the evidence, he said. Asked this month for an update on the investigation, Jablow did not respond.

Three current or recently retired Baltimore detectives who reviewed the case file told The Trace and BuzzFeed News that other investigators had pinned cases on dead suspects with little evidence in response to pressure from higher-ups to make it appear that more cases had been solved. When asked if Baltimore Police would conduct a broader inquiry into the department’s use of exceptional clearances, Jablow said, “As far as we know, there’s not a widespread problem.”

Williams’ murder case also remains open. The lead detective on the homicide said he collected several pieces of physical evidence — a hooded sweatshirt, a face mask, and a gun — that were discarded in the direction the killer ran. But fingerprints and DNA pulled from the items yielded no matches. And witnesses provided no names.

Baltimore Police denied The Trace and BuzzFeed News’ request for the case file on the murder.

Meanwhile, whoever shot Little in front of the grocery store remains unknown and potentially at large, just like the first person who tried to kill him.

The fact that Stokes’s first shooting had been closed, and now had been reopened, was news to his grieving mother. “Nobody said nothing to me. Nothing. Why am I not being called?” she asked. “It looked like to me, it was left alone.”

A city that fails to catch the vast majority of its shooters is failing to enforce the law. But the declining clearance rates recorded across the country do not reveal all of the harms and risks that unsolved shootings leave communities to endure.

Not only did all three of the men thought to have had a hand in the first shooting of Stokes later become victims themselves, two are also suspected by the Baltimore Police of going on to be involved in other armed crimes.

Violence, left unchecked, begets more violence, leaving devastated and terrified families in its wake.

At Little’s sentencing hearing, Tyreka Barnes, Stokes’s girlfriend, told the court how hard it was for her daughter to lose her father.

“My baby is six. She sees a therapist twice a week,” Barnes said. “Last week she told me that she wanted to die and be with her father.”

“We all sometimes get depressed. We get sad,” Tonia Cox, Stokes’s mother, told The Trace and BuzzFeed News. “I look at his pictures, and I cry.” Knowing that the assailants in her son’s first shooting were never caught, she added, also adds an element of fear to her grief. “I look at everybody hard,” she said. “I don’t let anybody get close to me.”

Little’s mother, Janice Moses, is enduring her own struggles. She is fixated on how her son could have been convicted of murder based on what seems to her such thin evidence, while both of his own shooters went free.

Her obsession, she senses, leaves her other children exhausted. They don’t visit her as often as they used to. Lonely and despondent, she sits waiting for Little’s nightly phone calls from prison.

During sentencing after his murder trial, the judge and even the prosecutor commented that it was clear Little had been raised in a loving home. Moses now spends a lot of time turning over every parenting decision she made, trying to determine where she failed her son.

“Devon always tells me, ‘Mom, you did the best you could.’ But I didn’t,” she said, shaking her head. “I could have done better.”

Her self-recrimination alternates with rage at the system that let her down.

“My son got shot twice, nobody done solve any of them crimes, or even questioned the fact why he got shot,” she said.

“I’ve just felt like they looked at my son like he nothing.”

Sarah Ryley is an investigative reporter for The Trace.

Jeremy Singer-Vine is the data editor for the BuzzFeed News investigative unit.

Sean Campbell is an investigative fellow for The Trace.

Additional reporting by Daniel Nass, Brian Freskos, Nolan Hicks, and Maria Zamudio for The Trace and Mike Hayes for BuzzFeed News.