Most gun stores face no legal requirements to secure the weapons they sell. This sets them apart from other businesses that deal in dangerous products, such as pharmacies and explosives makers.

Thieves have taken notice.

Easy Targets

Tracking stolen firearms through the black market, from gun store thefts to crime scenes.

This story was published in partnership with The New Yorker.

In the summer of 2014, Cruise Scott was 22 and looking for a quick way to make money. He lived with his grandmother near Fayetteville, North Carolina, a small city whose proximity to Fort Bragg and stubbornly high crime rate had earned it the nickname Fayettenam. A couple of years earlier, Scott had been arrested for possession of stolen goods, including cologne and a video-game console, and he served six months in state prison. After his release, in April, 2014, he got a job at a poultry plant and scraped by on about $250 a week; barely able to afford food, he began looking for new ways to fill his wallet. He thought about leveraging his network to sell drugs, but that was risky and required a big upfront investment, so he decided that it would be “too much of a hassle.” Scott had grown up around guns — he had been robbed at gunpoint and shot at — and had developed a liking for them. “It’s just a fetish, man. I love ’em,” he said. “Where we from, I’d rather be caught with it than without it.” He knew that he could make money selling guns to people with criminal records, who couldn’t buy them legally. He knew which brands — Glock, Sig Sauer, Beretta — were coveted on the street. Most important, he knew that gun stores in North Carolina had few security precautions, which made stealing from them easy. “It’s like taking candy from a baby,” Scott told me.

“It’s like taking candy from a baby,” Scott told me.

This story was published in partnership with The New Yorker.

Around 2:30 a.m. on August 5, 2014, Scott and his younger cousin Jeremy Aycock crept up to the front door of Mike’s Hunting Shop — a brick store with a green awning in Clinton, North Carolina — wearing bandanas around their faces. They used a screwdriver to pop open the door and, once inside, bolt cutters to make a slit in the floor-to-ceiling chain-link gate. As an alarm emitted a high-pitched beep, they shattered the store’s glass gun cases with a hammer. They grabbed as many handguns as they could carry and sprinted out the front door. “Hit and get out,” Scott said. “It was simple.”

Over the next four months, Scott and Aycock — often along with Ahkeem Pratt, Scott’s childhood friend — burglarized at least five more stores in the state, including Wilmington Guns and BullZeye Shooting Sports.

At Calypso Wholesale, in rural Duplin County, they sawed a hole in the roof and then used the shelves as a ladder to climb down into the store.

On at least two occasions, the crew piled into an SUV and drove up I-95, to New Jersey. Scott knew that he could make more money selling his guns in the Northeast, where stricter laws had made it more difficult for convicted felons and other prohibited purchasers to acquire firearms. “Up top, it’s hot,” he said. “If something comes their way, they jump on it.” In the suburbs outside Camden, they rented a room at a cheap motel, where they met Jonathan Shaw, another one of Scott’s cousins, and handed him the guns in a black duffel bag. They waited while Shaw and his associates sold the guns on the street. Scott didn’t ask much about this side of the business. “As long as you bring back my green, I don’t care who you’re selling to,” he said. Within a few days, Shaw returned and paid them their cut in cash. “He was just, like, ‘Keep ’em coming,’ and that was it,” Scott said.

By early November, the burglars had stolen some 200 guns — more than half of all the firearms lifted from licensed dealers in North Carolina that year. Their cache became so big that it was difficult to hide it all in their homes. “Guns were just everywhere,” Allan Wells, one of Pratt’s roommates, told me. “Under the bed, in the damned cabinets, under the oven.” According to Scott, the group netted around $60,000 or $70,000, which they used to splurge on bluejeans, Timberland boots, an Xbox, and jewelry. Their windfall could have been bigger, but, to reduce their stockpile, they offloaded some guns quickly in North Carolina, and even used them as a kind of currency: Scott gave a couple to Shaw as a tip, and traded a pistol with another associate for an electronic cigarette. Had Scott sold all the guns to the highest bidders in New Jersey, he thinks that he could have made at least $150,000. “The stock market goes up and down,” he said. “But guns — the demand for them stays the same.”

Scott’s spree tracks with a national trend: In recent years, burglaries at gun shops and other federal firearms licensees have increased, from 377, in 2012, to 577, in 2017. This is partly because guns are so readily available. There are some 63,000 licensed gun dealers in America — more than twice the number of McDonald’s and Starbucks locations combined. These retailers operate out of storefronts, pawnshops, and homes. (The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives doesn’t specify how many dealers are based in homes, but officials say that the majority of thefts occur in brick-and-mortar stores.) Federal regulators have set strict security protocols for other businesses that deal in dangerous products. Pharmacies must lock opioids and other controlled substances in fortified cabinets. Explosives makers have to keep volatile materials in boxes or rooms capable of withstanding explosions. Banks, in order to maintain federal deposit insurance, have to hire security officers. But there are no such requirements for gun stores, and criminals are taking advantage. Between 2012 and 2017, burglars stole more than 32,0000 firearms from gun dealers. “Lost and stolen firearms pose a substantial threat to public safety and to law enforcement,” the ATF wrote, in a 2012 report. “Those that steal firearms commit violent crimes with stolen guns, transfer stolen firearms to others who commit crimes, and create an unregulated secondary market.”

Only four states — California, Connecticut, Minnesota, and New Jersey — have enacted laws requiring gun stores to impose physical-security measures, but even those regulations tend to be narrow. Minnesota established security protocols 25 years ago, but they don’t spell out how violators are to be penalized. “They’re not really rules; they’re more like guidelines,” Richard Hodsdon, the general counsel for the Minnesota Sheriffs’ Association, told me. “I’m not even sure how many people who have firearms dealerships are aware of them.” Connecticut mandates only that dealers install alarm systems. But statistics suggest that even modest measures have proved effective: Between 2012 and 2017, states with physical-security requirements had lower annual rates of gun theft than those without. This takes into account the fact that thefts increased in California in 2016, as thieves figured out that they could bypass most safeguards by ramming cars through storefronts. When California is removed from the analysis, the annual number of burglaries in states with security requirements drops by as much as 84 percent. New Jersey has been especially successful at warding off burglaries. Rules adopted in 1971 require gun shops in the state to obtain approval for their security plans from the superintendent of the State Police before opening for business, and to keep weapons locked up. (In 2014, the Republican Chris Christie, who was then the state’s governor, proposed even stiffer requirements, but they were not adopted in full.) Between 2012 and 2017, burglars in New Jersey stole only three guns; burglars in North Carolina, meanwhile, stole more than 1,400.

“If you have to sit there for an hour and a half and put guns in a safe or a lockbox and then the next morning take them back out, that’s just not going to be cost-effective,” Charlie Lewis, the owner of BullZeye Shooting Sports, one of the shops that Scott burglarized, told me.

In 2017, lawmakers in Wisconsin introduced gun-store security bills, inspired by an anarchist who sent a rambling anti-government manifesto to President Donald Trump, stole more than a dozen firearms in Janesville, and allegedly made threats against schools and churches, causing them to go into lockdown.

The bills died in committees chaired by National Rifle Association-backed Republicans.

“The NRA has had such a stranglehold on the Republican Party for so long, and so many of those Republican legislators are depending on NRA money,” Lisa Subeck, a Democratic state representative and a primary sponsor of one of the bills, told me. “That gets in the way.”

At the federal level, Senator Dick Durbin and Representative Brad Schneider, both Democrats of Illinois, introduced bills in 2017 that would have penalized gun stores that failed to lock up their inventories, but the bills languished in committee for more than a year without a vote from the Republican-controlled Congress. Last week, Durbin and Schneider introduced similar legislation, called the SECURE Firearm Storage Act. “Dealers that benefit from a federal license should be expected to keep their inventories safe,” Schneider told me. Also in 2017, Senator Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina, and Representative Steve Russell, Republican of Oklahoma, sponsored alternative bills that would have doubled the maximum prison sentence, to 20 years, for stealing firearms from licensed gun dealers. Lawrence Keane, a senior vice president of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a gun-industry trade group, called the House bill “a significant reinforcement of our federal laws.” But this approach contradicts a growing body of research, which suggests that the probability of being apprehended is far more effective at deterring criminals than the severity of the potential punishment. And even this legislation failed.

Democratic state lawmakers in North Carolina told me that the issue of gun-store security requirements had never come to their attention. They were all supportive of the idea but said that it was likely a nonstarter in the Legislature, which is dominated by Republicans. Since taking control in 2011, Republican legislators have made it easier to acquire machine guns, allowed concealed firearms in bars and restaurants, and authorized gun owners to lock weapons in their cars on public-school grounds. Pricey Harrison, a Democratic state representative from Greensboro, told me that she thinks gun theft should be a nonpartisan issue. “If guns are getting stolen out of North Carolina because we don’t have proper security measures, and are being used to murder people in other states, we have got to fix that,” she said.

In August, 2014, the investigation of Scott’s burglaries fell to an ATF agent named Eddie Eubanks. At 44, Eubanks is stocky and spirited, with short black hair and a mild Southern drawl. Eubanks suspected that the break-ins were the work of the same group: The thieves often dressed in coveralls, wore their backpacks in front of them, and left tools behind at the scene; in two instances, he spotted Pratt’s shoulder-length dreadlocks peeking out of the hood of his sweatshirt. But the thieves wore gloves and masked their faces, so Eubanks was unable to pull fingerprints or figure out what they looked like. “We had nothing,” Eubanks told me. After the break-in at Calypso Wholesale, the ATF, the local sheriff’s office, and the National Shooting Sports Foundation offered a $15,000 reward for any information leading to the arrest and conviction of the thieves.

“We knew these guys weren’t going to stop until we caught them,” Eubanks said. “They were having an easy time of it. They were good at it. They were quick.”

By December, 2014, law enforcement officers had recovered eight of the guns at local crime scenes. In Fayetteville, police found a .45-caliber Springfield Armory handgun from Calypso Wholesale on a 25-year-old after he held up a Scotchman convenience store and threatened to kill the clerk. In Harnett County, sheriff’s deputies said that they found an assailant, who had attempted to rob an 18-year-old at gunpoint, in his girlfriend’s bedroom with a .380-caliber Bersa handgun from Firearms and Etc. within reach. ATF informants and agents were intercepting some of the guns in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, raising alarms within the bureau. Agents rushed to set up undercover buys in the hopes of stopping the weapons from being used in violent crimes. Eubanks recalled supervisors telling agents, “If you got to spend thirty grand to get the guns off the street, that’s what we have the money for.” Those efforts paid off. In 2015, the ATF brought charges against a high-school counsellor from Camden who had helped Shaw sell guns while running a nonprofit track program for kids. Agents also arrested an associate of the counsellor, a 41-year-old hospital clerk who was caught hawking guns out of his Nissan Maxima while wearing his scrubs.

Eubanks was tracing the guns through the so-called Iron Pipeline, a trafficking corridor that funnels firearms up I-95 from less heavily regulated states, in the South, to states with stricter gun laws, in the Northeast.

Scott’s scheme began to unravel in the fall of 2014, after an ATF lab found Aycock’s DNA on a pair of bolt cutters left at Calypso Wholesale. When Eubanks confronted Aycock, he gave up his two accomplices. Three days later, Scott was watching the movie “Scarface” with his girlfriend, who was pregnant, and Pratt, when they heard a knock at the front door. Scott looked outside, saw police surrounding the apartment, and threw on a shirt. “I love you,” he told his girlfriend. “Take care of my son.” He and Pratt ran out the back door as officers stormed through the front door. “You ever seen a swarm of bees?” Scott’s girlfriend asked me. “That’s what they looked like.” They caught up with Pratt and shot him with a Taser. Scott darted through yards, hopped over fences, and then hid in a tall green trash can for hours. He spent the next six months on the run. At some point, he drove up to Philadelphia to sell the last 10 or 15 guns he had. Eventually, a police dog led officers to a house in Kinston, North Carolina, where they found Scott curled up underneath a porch and arrested him. Eubanks called the jail when he learned that Scott was in custody. “Do not let that guy go,” he said.

The three burglars took pleas, and Scott received a 14-year prison sentence, which he is now serving in a federal penitentiary. When I interviewed him in December, 2016, in a state prison in North Carolina, I asked him how he felt about the fact that the guns he stole wound up being used in crimes. “I don’t feel guilty about nothing,” Scott said. “People make their own choices, and at the end of the day they’re responsible.” (Pratt and Aycock declined requests for interviews.) Eubanks said that the thefts by Scott and his team have had far-reaching repercussions; they demonstrated how easy it was to steal guns, which led to a wave of copycat group burglaries. “Yes, we had gun-store break-ins,” Eubanks said. “But since this happened, in 2014, North Carolina and South Carolina gun thefts have significantly increased.”

Even with the crew behind bars, the guns cut an arc of violence across the country. It’s difficult to discern the full scale of gun trafficking in the United States, owing in part to the Tiahrt Amendments, a series of provisions that Congress began passing in 2003. The amendments bar the ATF from publicly disclosing detailed information about the provenance of individual guns used in crimes. The NRA pushed for the provisions and has fought efforts to repeal them, arguing that public access to the data would unfairly stigmatize businesses and violate the privacy of gun owners. Before the passage of the Tiahrt Amendments, reporters and researchers could use the ATF’s data to determine whether a stolen gun had been recovered at a crime scene. Today, tracking such weapons is painstaking, and requires cross-referencing the serial numbers listed on reports of stolen guns with those on police reports for crimes. The Trace and The New Yorker, working around the Tiahrt Amendments, relied on thousands of public records and more than 50 interviews to track Scott’s guns through a network of black-market profiteers.

Within three years of Scott’s first burglary, at least 68 of the guns his crew stole were involved in crimes.

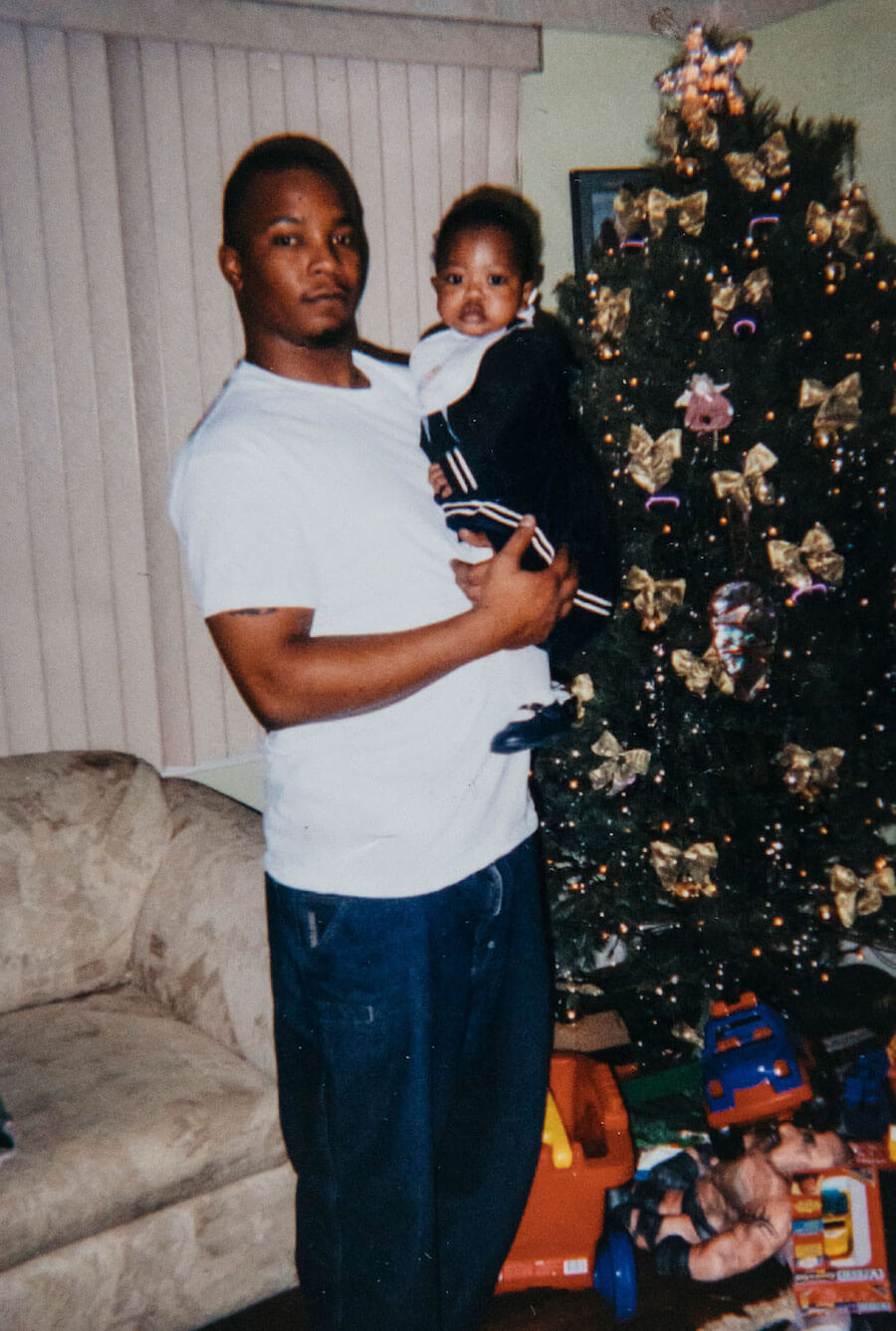

At least one of the guns ended up in Maryland. On May 10, 2015, in Baltimore, Harry Davis, Jr., was preparing a Mother’s Day celebration for his wife, Zoronda, and his mother, Deborah McMillion. Davis was 36, stood more than 6 feet tall, and had buzzed hair and a goatee; his friends knew him as Huck or Big Guy. He earned a living fixing up homes with his cousin and enjoyed angling for catfish in the Choptank River, coaching youth football, and playing video games with his 16-year-old son, Shamond. Davis and Zoronda had been friends for nearly a decade when, in 2007, he confessed that he was secretly in love with her. “He had me call my mother on my cell phone to tell her how much he loved me,” Zoronda told me. “No one’s ever done that.” They got married just a few months before that Mother’s Day. Davis spent the afternoon grilling salmon to top with crab and shrimp. He presented Zoronda with cards from each member of their immediate family, and ghostwrote ones from Sir Cameron, their 6-month-old son, and Candy, their pit bull.

After dinner, Davis relaxed in the backyard, enjoying the warm night with a Black & Mild cigar. Around 10:30 p.m., Matthew Hughes, a stocky 32-year-old, walked out of Pepper’s Liquors, which is on the other side of a nearby alley, carrying a beer in a black plastic bag. Surveillance footage from the liquor store shows that Hughes stopped by Davis’s chain-link fence to talk to him. A moment later, they were joined by an acquaintance of Davis’s named Marquis Richardson. Davis and Richardson sometimes played cards in the backyard, and when Shamond was young, he went to a day care run by Richardson’s mother. Richardson had spent time behind bars for conspiring to sell drugs; when he was released, Davis tried to help him get a job. Hughes was new to the neighborhood, and also had a rap sheet. He had been convicted of possessing drugs and an illegal weapon, and had served several years in federal prison before being released, in 2014.

What the three men talked about at the fence is unclear. But, after about a minute, Davis turned to walk toward his house. Hughes pulled out a pistol and shot him in his lower back, thighs, and just above his right elbow. Zoronda rushed out of the house in time to see Hughes and Richardson running down the alley. She collapsed to her knees, felt for Davis’s pulse, and started performing CPR. Shamond called 911. When the ambulance took too long to arrive, he leaped over the fence, sprinted to the fire station, and shouted for help: “My father’s been shot!” Paramedics sped Davis to Sinai Hospital, where doctors tried in vain to save him. He died at 11:53 p.m. Zoronda sneaked into a restricted part of the hospital to say goodbye.

About 30 minutes after Davis was shot, his neighbors heard gunfire from an alley a block from his house. Police arrived at the scene to find Hughes lying face down on the asphalt, with point-blank gunshot wounds to his face and torso. He died soon after. The lead detective on Davis’s murder investigation thinks that Hughes had tried to rob Davis, and, when Davis rebuffed him, Hughes opened fire. Detectives speculate that Richardson shot Hughes as payback for Davis’s death. (Davis’s family wishes that the police had investigated further, and could provide them with more clarity about the killing. Richardson turned down several requests to be interviewed for this piece, and, on Christmas Day in 2018, he, too, was killed in a shooting.) Because of Hughes’s criminal record, he was not legally allowed to have a firearm, but, in the right side of his waistband, officers recovered a pistol that matched the shell casings found next to Davis’s body: a 9-mm. Ruger SR9c, with a black frame and a scuffed stainless-steel slide. Cruise Scott had stolen it from Calypso Wholesale.

In early 2017, I visited Deborah McMillion, Davis’s mother, at her home in Baltimore. She sat at her dining-room table with faded photographs of Davis arrayed in front of her.

“He’s an only child, so I captured every piece of his life,” McMillion said. “One of the things I miss the most are my phone calls. ‘Hey, Momma, how you doing? I didn’t want nothing. I was just calling to say hi and I love you.’ ”

For a time, McMillion kept a lawn chair in her car so that she could sit and read by Davis’s grave on her way home from work. Shamond got a tattoo on his arm of a football under the words “Big Huck.”

When I visited her new home, she had just wrapped up a twelfth-birthday party for her daughter Aniya, who witnessed the shooting. Aniya’s bedroom walls were adorned with little notes that she had addressed to her father. In one, she wrote that she missed “the way you laughed and your bad Dance moves.”

Sir Cameron is now 4. He recently asked Zoronda where his father was. “Your daddy’s in Heaven,” she told him. “Can I go visit?” he asked.

Zoronda believes that Davis would still be alive if Hughes had never acquired the Ruger pistol.

She places some of the blame for his death on the thieves who introduced the weapon into the black market. “No, you did not directly pick up that gun and kill him,” she said. “But, damn it, it could have been a lot harder.”

This gun-trafficking map is based on the most recent comprehensive data furnished by the ATF, from 2017, and illustrates the top hundred routes of guns that were purchased in another state at some point prior to 2017, and subsequently recovered in connection with a crime. The map excludes firearms that were recovered in the same state in which they were originally purchased; in every state, this category accounts for the largest share of guns recovered in association with crimes.

The analysis, which shows that states with physical gun-store-security requirements experienced lower rates of theft, is based on the ATF’s theft and loss reports from 2012 to 2017.

Design and Development by Richard Sancho and David Kofahl

Data Visualization by Daniel Nass

Additional Research by Natalie Meade and Alex Yablon

Video by Catherine Spangler and Monica Racic