For most people, Easter is a time for celebration, a reflection on rebirth. For Movita Johnson-Harrell, the holiday evokes feelings that are much more somber. It was on Easter Sunday in 1975 when gun violence claimed the first of five lives in her immediate family.

From that night on, violence has been a constant. Her father, her brother, a cousin, and her two sons all have been killed since that day.

The losses suffered by Johnson-Harrell’s family illustrate how deeply gun violence has affected Black communities in Philadelphia and in other cities throughout America across generations. Despite being just over 13 percent of the U.S. population, Black Americans account for nearly 60 percent of firearm homicide victims each year. That equates to Black people being over 11.5 times more likely to be victims of firearm homicide than their non-Hispanic white peers. In Philadelphia, Black people have accounted for about 80 percent of gun homicides in recent years.

Over time, these intergenerational losses have left many families stuck in a seemingly unending cycle of trauma. The causes are complex, but a close look at the stories of Black Philadelphians points to a primary driver that has persisted for more than a century: racism.

Systemic exhaustion

The “100 Shooting Review Committee,” a 2022 report written by eight Philadelphia city agencies, concluded as much. It shows how the most racially segregated Philadelphia neighborhoods — which are also the areas in the city with the most gun arrests — face the highest concentration of 18 “indicators of disinvestment,” including poverty, dropping out of high school, and eviction and foreclosure. “Structural racism has caused disinvestment and poverty in specific areas of Philadelphia, which has, in turn, created the conditions in which shootings occur,” it stated.

The problem is not new. It’s not a product of COVID-19 or young people fighting over online beefs. As far back as the late 19th century, Roger Lane wrote in “Roots of Violence in Black Philadelphia: 1860-1900,” the city’s Black homicide rate climbed disproportionately, from 6.4 per 100,000 residents in the 1860s to 11.4 in the 1890s.

“All three phenomena — crime, gun use, and homicide itself — were in turn related not only to each other but to the systematic exclusion of the black population from the opportunities opened up by the urban industrial revolution,” Lane wrote.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the economic and political gains that Philadelphia’s Black community had made following the Civil War and Reconstruction started to dissipate as the result of white bigotry and resentment, according to Lane and other historians. “The impact of job loss, segregation, and the loss of political power on the black homicide rate in Philadelphia was startling,” Randolph Roth wrote in his 2009 book, “American Homicide.”

Johnson-Harrell feels this historical truth in her bones. “We have not addressed poverty, the disinvestment in education, the inability to get jobs, food deserts, housing scarcity, gentrification, mental illness, drug and alcohol abuse,” she said. “We haven’t addressed any of that — but we expect people not to kill each other.”

‘The images would not leave my head’

Johnson-Harrell is a lifelong Philadelphian who was raised in a family fractured by domestic violence, sexual abuse, alcohol, and drug addiction. The details of the murder of her father, Allen Christopher Hargett, are still vivid.

Her parents were working on reconciling, which led them to eat Easter dinner at her grandfather’s house. After the meal, Hargett drove Johnson-Harrell, her mother, and her siblings back to their North Philly apartment. The children went inside. Then, two men pulled up in a car, jumped out, and ran toward the porch, where her parents were talking.

From a second-floor window, Johnson-Harrell watched the gunmen fire shotguns that made her ears ring; they blew her father off his feet and onto his back. The car took off, her mother screamed, and she and her brother ran out.

“Everything started moving slow in my little 8-year-old brain,” Johnson-Harrell said. “I kind of blanked out for a moment.” That night, she had her first taste of hard liquor.

She saw her mother kneeling next to her fallen father, cupping his body in her arms. Her two-piece Easter petticoat outfit was drenched in blood.

The next morning, her mother, still in her Easter clothes, told her that her father was dead. “I kept hearing the sounds of the gunshots and of him gurgling his own blood as he gasped for breath. The images would not leave my head,” Johnson-Harrell wrote in her memoir, “Phoenix Ascending: My Rise From the Ashes.” They “were haunting me day and night.”

Her mother’s ex-husband and his accomplice were charged with the killing and sent to prison, said Johnson-Harrell. And so her father’s slaying became the opening chapter in a multigenerational saga that fractured her family.

‘Trauma that goes back to slavery’

Berto Elmore, a longtime Philadelphia criminal defense attorney and community activist, said all of his clients in gun cases are Black males.

A common denominator among them is what he describes as self hatred, which he believes is rooted in rage fueled by racism. That hatred has been a factor in Black America for generations, a vestige of slavery, and it drives many Black men to act violently toward other African Americans at a rate unseen in other races, said Elmore, 73, who is Black.

“Our self hate is not the only reason for gun violence and Blacks killing Blacks, but it’s certainly one of the major reasons,” he said. A favorite historic quote of his is from slain civil rights leader Malcolm X: “The worst crime the white man has committed has been to teach us to hate ourselves.” The prevalence of guns, Elmore said, can worsen an already volatile situation.

“We have to deal with this trauma that goes back to slavery. … There needs to be mandatory trauma classes in every school where there’s a lot of Black people,” he said. “This is a cultural thing.”

Menika Dirkson, a history professor at Morgan State University who was born and raised in the Germantown section of Philadelphia, sees similar connections tied to the legacy of slavery. “If people are constantly having to struggle for survival,” she said, “it means that some small portion of the population is going to [be mired in] poverty and do some crime that leads to death, fear, and violence that will continue on a cyclical basis.”

‘Committed to fixing me’

Although the city does not keep statistics on victimization spanning multiple generations of families, it is not uncommon in cities like Philadelphia, where the gun violence rate in the African American community has consistently surpassed the national average.

Like Johnson-Harrell, Jacqui Sorrells, 65, is part of a family that has faced generations of violent deaths. She was 11 when her father, Neumar Scales Sr., suffered a fatal slash to the throat in the West Philadelphia bar where he worked in 1970. She followed her mother’s lead by not talking about it for years.

She was still processing that trauma when her brother, Neumar Scales, Jr., was shot to death eight years later. Sorrells, then 19, heard gunfire outside the family’s Southwest Philadelphia home, then a thump against the front door.

When she opened it, she heard “the worst labored breathing that I’ve ever heard in my life.” Her brother wasn’t moving. She was told he died in the hospital, but she knew he had passed in her arms, “because the breathing stopped.”

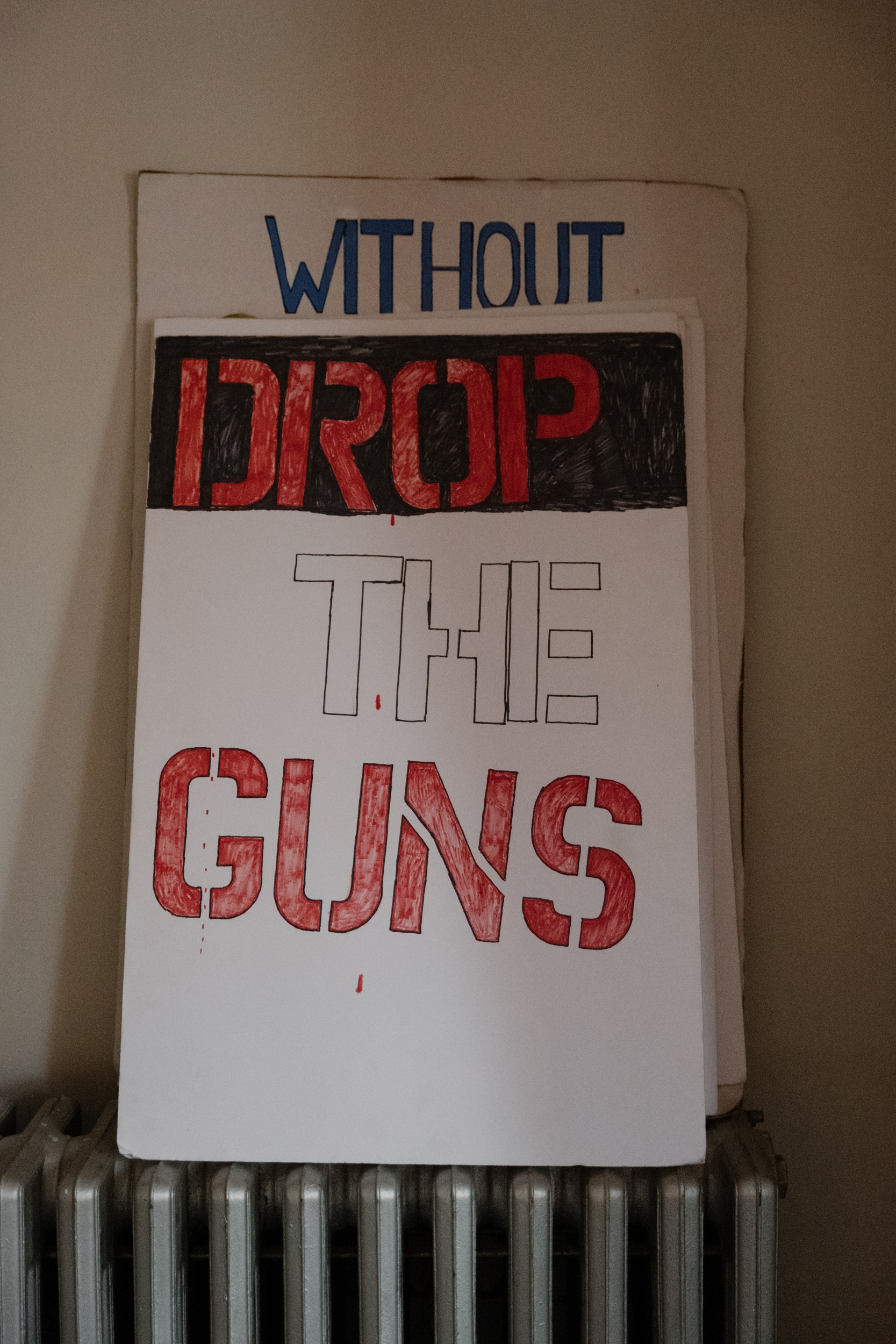

Caroline Gutman for The Trace

Caroline Gutman for The Trace

Neumar Scales Jr. was 18, and had recently become a father. Sorrells still doesn’t know who killed him. “Black crime really wasn’t investigated,” she said. Years later, she learned that her brother had been in a street gang.

Despite their close relationship, she can’t remember his voice anymore. “I buried that pain so deep that I don’t remember us playing together, what movies we watched together, what music we danced to together,” she said. “I had no skills and no knowledge of how to deal with that level of pain except to ignore it.”

Twenty years later, in 2000, Sorrells was haunted again when her nephew, William Neumar Jones, 17, was gunned down after getting into a dispute on a city bus. As she recalled, “I am,” as he was known, was a beloved star athlete at West Philadelphia High School. On the day of his funeral, the church and the streets surrounding it were filled with teachers and students.

“Whatever you don’t fix, you pass on. I am committed to fixing me,” Sorrells said. She sought help from Mothers in Charge, Inc., an anti-violence organization whose members are primarily women who’ve lost loved ones to violence. Sorrells eventually became a volunteer in 2005 and a full-time staffer in 2022. She juggles the titles of victims of crime advocate, outreach coordinator, youth mentor, and peer grief-support specialist.

“We say, ‘generational curses,’” Sorrells said. “But it’s actually generational brokenness.”

Cycles of violence

By July 1991, Johnson-Harrell was a 26-year-old reformed drug addict and dealer. Her brother, Charles Anthony Johnson, 28, was stabbed to death in a domestic dispute. A month later, Johnson-Harrell gave birth to a daughter, Charlyne Antonia, named after him. In 1992 Johnson-Harrell had her fourth child, Charles Andre, also named after her brother.

Twenty years after her brother’s death, in January 2011, it was Charles Andre who fell victim to violence when two gunmen opened fire on him as he sat in a car waiting to pick up his sister. Just 18, and an expectant father, investigators found that Charles Andre Johnson was the victim of mistaken identity.

Between these shootings, Johnson-Harrell earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Pennsylvania, was hired by Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner to aid victims of violence, and, in March 2019, became the first Muslim woman elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

Her political triumph was cut short. In January 2020, she pleaded guilty to perjury, tampering with public records, and theft by unlawful taking. Those and related crimes stemmed from her decade-long personal use of $500,000 from the nonprofit organization she founded. After three months in a Philadelphia jail, she was released to house arrest in August 2020, and completed her probation this January.

In March of 2024, Krasner hired Johnson-Harrell again — this time to be a consultant assisting witnesses and survivors of crime. Krasner said she’s paid her debt. Later in the year she took a job as spokesperson for the Philadelphia Sheriff’s Office.

She’s continued to cope with the long tail of gun violence. Ten years after Charles Andre’s murder, Johnson-Harrell’s surviving son, Donte Johnson, 30, dodged death when a gunman opened fire on a group of people he was standing with on a Philadelphia sidewalk. His cellphone was shot out of his hand. A month later, Donte was fatally shot while visiting Los Angeles with friends.

Even though Johnson-Harrell is heartened by the recent decrease in shootings across the city, she’s “terrified” for her grandchildren, who are almost in high school.

So after decades of living, losing, and giving back in Philadelphia, she’s preparing to leave the city that multiple generations of her family have called home. She’s planning to move to Sierra Leone, where she has traced her ancestry. She believes her grandkids will be safer there.

“This country has taken enough from me,” Johnson-Harrell said. “I used to always say, I can’t leave here, my sons are here. My sons aren’t here, their graves are here. And they’re together.”

The Trace’s reporting in Philadelphia is a part of the Every Voice, Every Vote project and supported as well by the Comcast NBCUniversal Foundation, The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, the Neubauer Family Foundation, and the William Penn Foundation. You can read more about The Trace’s Philadelphia supporters here, and read our editorial independence policy here.