On an unseasonably warm night this past September, the room was quiet. The only thing the seven people sitting around the table knew about each other was that their lives had been marked by gun violence.

That’s how it all started — seven survivors, gathering in Bronzeville every month to tell their stories as the streetlights glowed to life, casting yellow halos through the large conference room windows. They were there as part of the Survivor Storytelling Network — an initiative by The Trace to empower gun violence survivors to publish their stories in their own words. The daily news cycle’s recounting of stories about gun violence can be minimal and dispassionate. Here, the people who are the subjects of crime coverage become the writers, and they tell the story of gun violence in this city in a different manner.

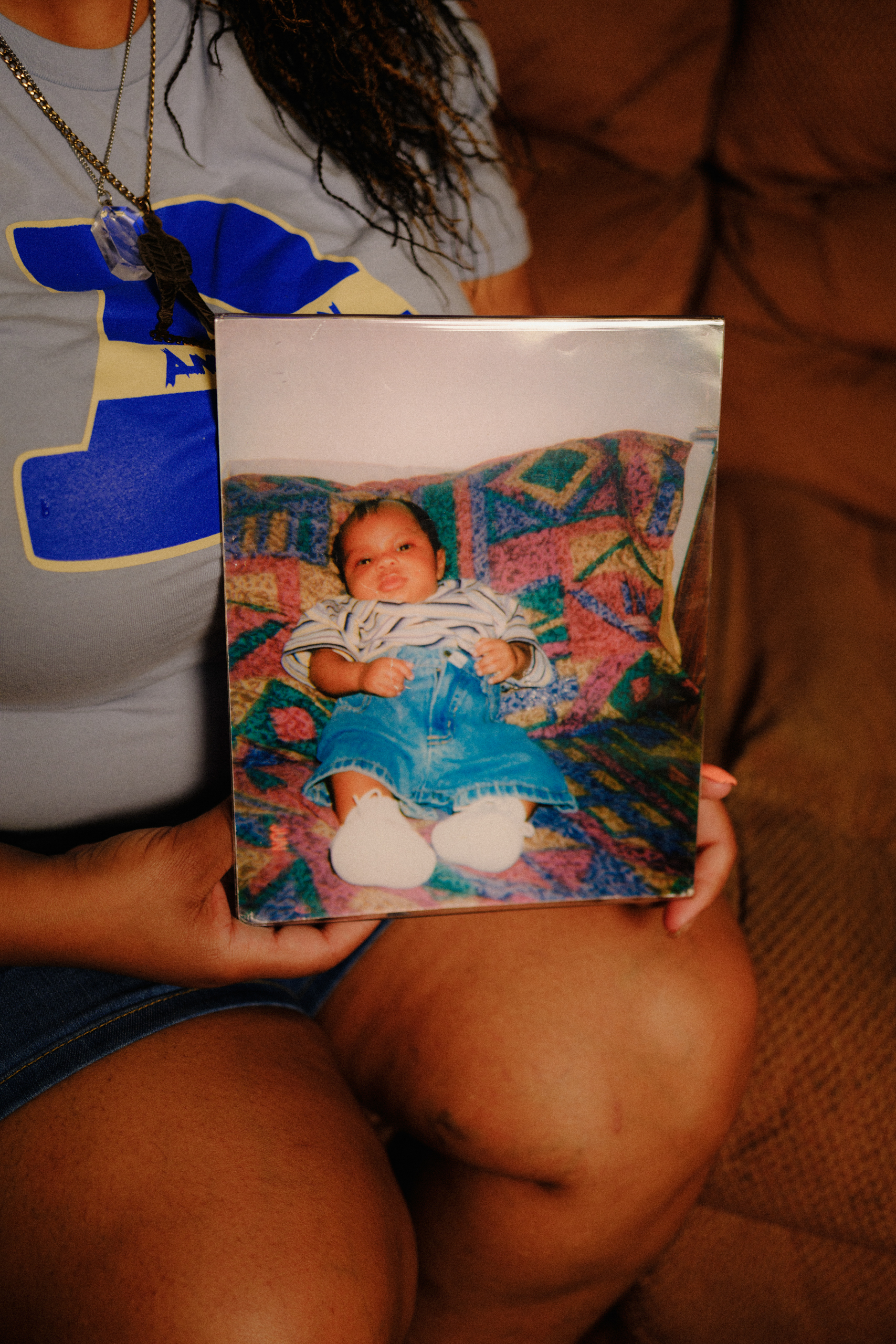

They’ve opened up about their experiences so we might all learn — in a much kinder way than they did — about how gun violence reverberates far beyond its victims, affecting families, friends, whole communities. They show people who fortunately do not have a seat at that tragic table why the crisis truly is everyone’s problem. And the survivors’ reflections reveal, too, different possibilities for combatting gun violence.

As Melinda Abdallah said at the very first meeting and many times after, she’s telling her story, “so no one else has to go through this.”

After several meetings, the survivors would come to know each other not only by their own names but also by the names of those they’ve lost.

Akilah Townsend for The Trace

Akilah Townsend for The Trace

Although the people telling their stories are connected by the same horror, their experiences of mourning and healing were all very different.

For some, the loss is painfully recent. Others have been grieving for nearly three decades. Some are part of bereavement groups; others have rarely talked about what happened. Some have weathered the challenges of parenting in the midst of mourning. Others have felt excruciatingly alone in their grief.

But over the course of two months — during which they shared their oral histories, learned the basics of journalistic writing, examined how their stories connect to broader conversations about gun violence, and crafted a vision for their essays — they learned that they are connected by more than just loss.

They shared, for example, an aching need to know more about what happened to their loved ones, and why.

It Took 25 Years to Put Together the Missing Pieces of My Siblings’ Murders

If a Trauma Center Had Been Closer, My Best Friend Might Still Be Alive

I Wasn’t Allowed to Touch My Son After He Died

I Want to Change the Culture of Silence

My Community Had No Support Groups for Gun Violence Survivors. So I Started My Own.

University instructor Jessica Brown explores that need to know in her essay chronicling her two-decade-long quest for documents about the murder of her siblings.

For Melinda Abdallah, whose son Jacob was shot in Little Village, it was the lack of information — when no one in the neighborhood was willing to come forward about the shooting — that turned her into an activist.

What brought each of the survivors to this program was not that need to know, but the urge to share.

My Children Were Killed in Different Neighborhoods. Only One of Their Deaths Seemed to Matter.

I Know What It Takes to Keep Young Men From Ending Up on Either Side of a Gun

Because as Tamika Howard pointed out, even though “we reinjure ourselves every time we tell our stories,” they hope that doing so might change something, might make it so that others won’t have to suffer in this way.

That’s why Estela Díaz flagged down Mayor Brandon Johnson at a rally and told him the story of how officers did not allow her to hold her son after he was killed. She hopes telling that story will change the way the justice system treats survivors.

By telling the stories of her son and daughter, Delphine Cherry has helped convince legislators to support bills that could help curb gun violence.

For Corniki Bornds, sharing is about saving her own community. After her son was killed, there was such an overwhelming need for people to share and commiserate, that a support group formed almost automatically. She helped give it a name, a place, and some structure.

For Juan Rendon, however, the person he survived is the person with whom he would have shared his grief. His essay, this experience, is the first time he has really talked about it since Junior was killed 12 years ago.

At the first meeting, he earned silent nods from everyone when he gave voice to something else that connected them all. He smiled as he invoked Dia de Muertos and the movie “Coco.” “Remembering them is how we can keep them alive,” he said.

In these essays, you’ll find details that are hard to read; you’ll find anguish and anger. You’ll find love and hard-won healing. You’ll find people delving back into their darkest moments to share them with you, in hopes that you’ll connect with something, too.

Connection, they show, is how you take an impassive line item in a news story and turn it into impactful legislation or a pioneering support group, or even just one person feeling like they can share their story, too.

From Our Reporters

When Your Loved One’s Body Becomes ‘Evidence’

‘We Can Still Hear Each Other’: The Loss Only a Sibling Knows

Chicago Officials Promised to Support Shooting Survivors, But Many Feel Overlooked.

Chicago Promised Better Mental Health Care. Shooting Survivors Say They Haven’t Seen It.

They Couldn’t Find Help When They Survived a Shooting. They Want Things to Improve for the Next Generation.

Grieving Takes Time. Gun Violence Survivors Say They Don’t Get Enough of It.

Navigating the Justice System Is Daunting — Especially If You’re Grieving

Credits

Project manager: Crystal L. Paul

Chicago staff reporters: Rita Oceguera, Justin Agrelo

Editor: Joy Resmovits

Visuals editor: Selin Thomas

Production and development: Chip Brownlee

Photography: Akilah Townsend

Audience engagement: Victoria Clark and Sunny Sone

Published in partnership with the Chicago Sun-Times, the Chicago Reader, Block Club Chicago, and City Cast Chicago

Funders of The Trace’s Chicago bureau include the Joyce Foundation, the Alvin H. Baum Family Foundation, the Field Foundation of Illinois, Polk Bros. Foundation, and the Jacob & Valeria Langeloth Foundation. You can find our donor transparency policy here and read our editorial independence policy here.

Special thanks to The Trace’s people operations manager Tracey Johnson, executive editor Craig Hunter, and our community partner, City Bureau.