In the summer of 2006, Micha Eatman, then 17, and two others were charged with beating a 14-year-old and robbing him of his cell phone in Chicago. The beating put the victim in a coma. Though he eventually recovered, he lost peripheral vision in one eye and was left with memory problems.

Eatman was sentenced to seven years behind bars but released early two years later. He was convicted of two more felonies over the ensuing decade. After his third release from prison, in 2023, Eatman was arrested and charged with being a felon in possession of a firearm.

Facing a 10-year sentence, Eatman challenged his indictment. He argued that the federal law banning him from having guns was unconstitutional under a new test laid out by the Supreme Court in New York Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, a landmark 2022 case that dramatically expanded Second Amendment protections. A district court judge agreed and dismissed the charges. Eatman’s attorneys did not respond to requests for comment.

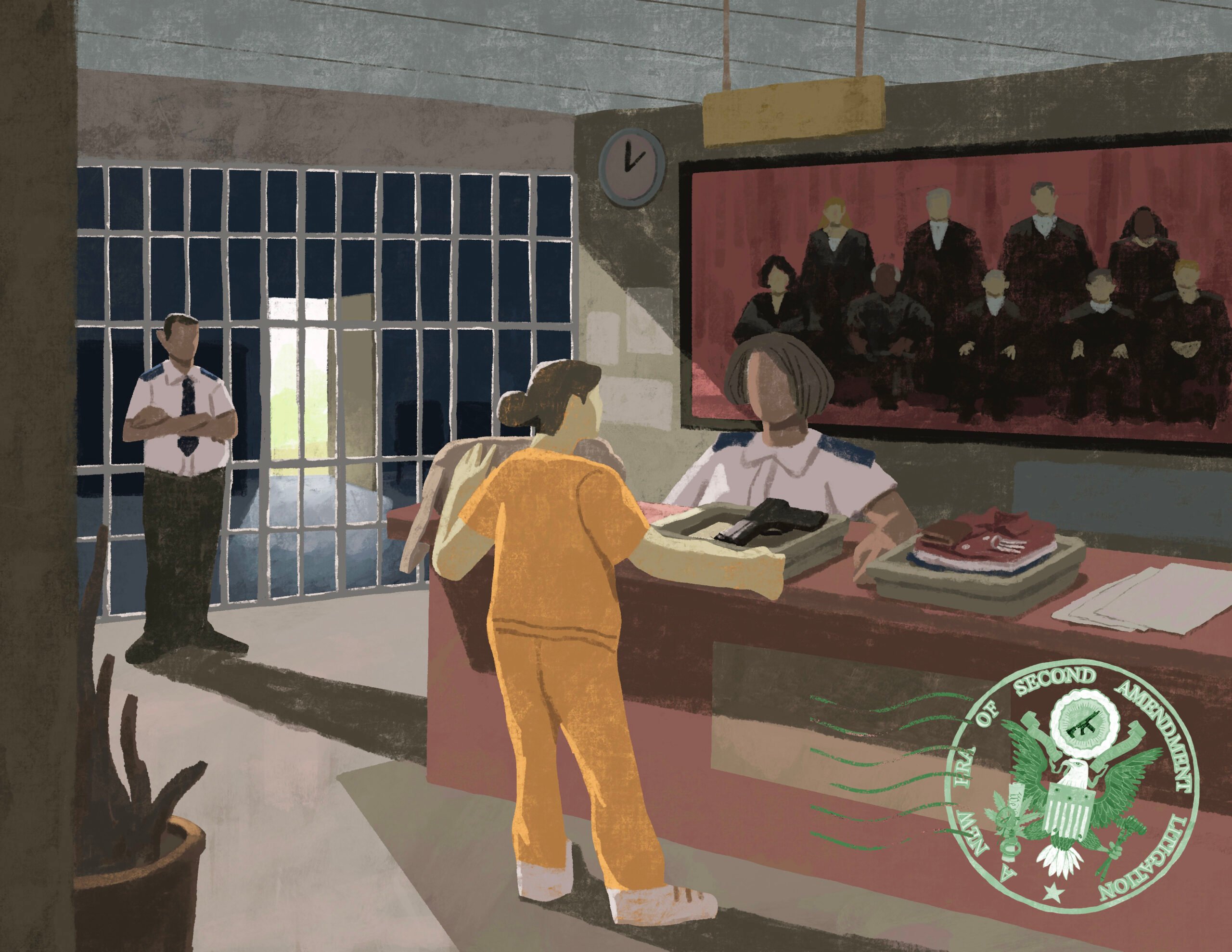

Bruen set off a wave of legal challenges to gun restrictions across the country, but no other group has taken to the courts as frequently as people with felony convictions, who are prohibited from possessing guns under a federal statute known as the felon gun ban.

The Trace reviewed more than 2,000 federal court decisions that cited Bruen over the past two years. More than 1,600 of them answered challenges to a wide variety of federal, state, and local gun laws — from assault weapons restrictions to bans on guns at the U.S. Post Office. The majority — some 1,100 — of the decisions included a challenge to the felon gun ban, making it the single most frequently contested statute by far.

At least 30 of the challenges to the felon gun ban have succeeded. While that ratio may seem small, it marks a stark departure from the past, when effectively none succeeded, and it shows that Bruen has cracked the longstanding consensus that people convicted of serious crimes may constitutionally be barred from gun ownership.

Those decisions, albeit rare and frequently narrow, chart new legal pathways for other defendants and judges to follow, meaning that more people convicted of felonies could have their cases thrown out.

Over the past two years, judges have issued on average two Bruen-related rulings each working day, the majority of which have been on challenges to the felon gun ban. And the pace is increasing.

Judges and prosecutors grapple with Bruen’s mandate

The cases reviewed by The Trace make clear that Bruen has saddled judges and prosecutors with increasing caseloads, and they are wrestling with how to apply the Supreme Court’s ambiguous methodology.

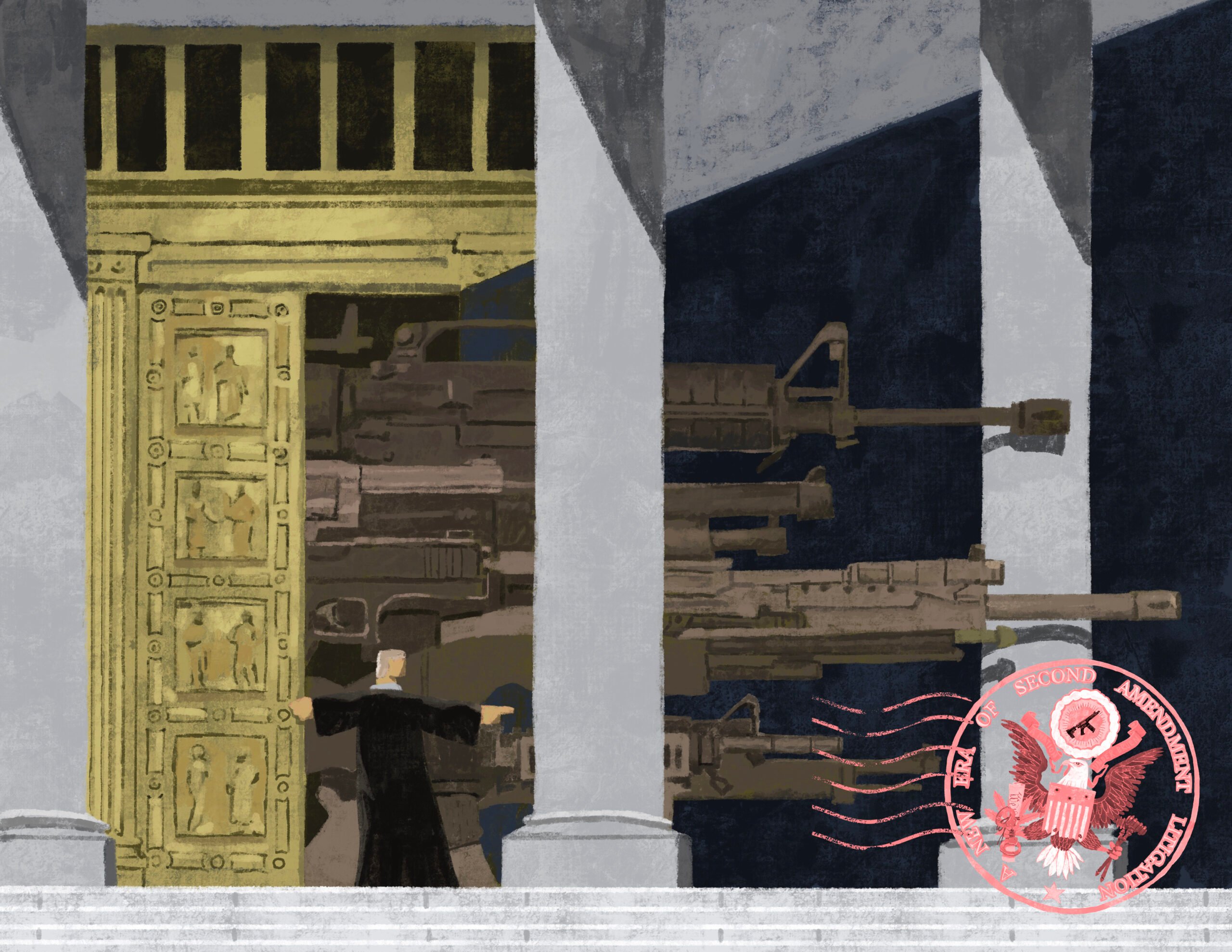

Bruen laid out a new test for evaluating the constitutionality of gun laws. Judges used to be able to consider modern-day concerns like the efficacy of a law in preventing crime, technological changes to firearms themselves, and rising rates of gun deaths. Now, those concerns are no longer relevant. Bruen says a gun regulation is constitutional only if it is consistent with the nation’s “history and tradition of firearm regulation.”

The new mandate has created confusion and frustration in courtrooms across the country. Prosecutors have been required to compile what amounts to American history theses to justify charges against people with felony convictions who were allegedly caught with a firearm. Judges must be experts not only in the intricacies of law but also in the nation’s often conflicted history of firearm regulation, a task for which many feel ill-equipped.

“I am not a historian, nor was I trained as a historian,” Sara Ellis, a federal judge in Chicago, told attorneys gathered in her courtroom in February, as she considered motions from five defendants challenging the felon gun ban in an effort to have their criminal charges dismissed.

“We are in this box that we were placed in wrongly, and I am struggling,” Ellis said, according to a transcript of the hearing.

Prosecutors seeking to uphold the felon gun ban have been forced to rely on centuries-old, discriminatory statutes.

In the case before Ellis, the U.S. Attorney’s Office cited laws from the 1700s that disarmed Catholics, African Americans, and loyalists to the British crown — groups whom early Americans viewed as “dangerous” or “untrustworthy.” They also argued that because most convicted felons used to be executed, the less severe punishment of a permanent gun ban should pass constitutional muster.

Ellis disagreed. She ruled that the old gun bans differed from today’s in that they were not permanent and had exceptions, like for African Americans whose enslavers permitted them to possess guns. Despite her “deeply visceral misgivings,” Ellis dismissed the charges against the defendants as unconstitutional.

Many other judges have found themselves issuing rulings with similar unease. “This Court is also not sure that ceding this much power to the dead hand of the past is so wise,” Carlton Reeves, a federal judge in Mississippi, wrote in a 2023 order dismissing a federal criminal charge against a defendant, who remains out on bond while the government appeals.

The sheer volume of Bruen challenges to the felon gun ban has the potential to gum up the legal system. Margaret Groban, a former federal prosecutor who focused on gun crimes and domestic violence cases, described the fallout as “a mess.”

“It does take up a lot of resources,” she said. “There are cases to prosecute, and then you spend all your time defending the cases that have already been prosecuted.”

A former federal judge, Paul Grimm, said that, a decade ago, it was rare to see people convicted of felonies challenge their gun bans. “You never would have heard of a convicted felon saying, ‘I have a constitutional right as a convicted felon to have a firearm,’” Grimm said. “You didn’t see those kinds of things.”

Grimm also said judges are expected to apply Bruen’s framework without much guidance. “The trial judges will work themselves like rented mules to try to do what they’re told they have to do,” he said. “However, they can be forgiven for hoping that when they’re instructed to do something new, there would be sufficient guidelines.”

Groban worries about public safety implications. “It’s all part and parcel of the same kind of road we’re going down that all makes us less safe — that elevates the Second Amendment and disregards public safety and personal safety,” she said.

Hope for defendants and public defenders

A felon in possession of a firearm is one of the most commonly charged federal crimes, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission. In 2022 and 2023, more than 7,000 people with felony records were convicted of this crime — in the federal court system alone.

The majority of these defendants were Black, reflecting the criminal justice system’s racial inequities, which have left thousands of people with felony convictions for minor drug offenses like marijuana possession.

In The Trace’s review, the majority of defendants challenging the felon gun ban were represented by public defenders, who see Bruen as an unexpected opportunity to challenge a statute that has long resulted in mass incarceration.

“I represent a lot of kids who have never in their lives even fired a gun,” said Christopher Smith, a public defender in the Bronx. “But it’s a dangerous neighborhood.” His clients, he added, would rather be tried for carrying an illegal gun than killed for not having one to defend themselves.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

Bruen has shifted the legal strategy in gun possession cases, particularly for clients who had prior felony convictions, Smith said. “The biggest change is now we just write a different motion in gun cases, where we challenge on Second Amendment grounds.”

But in New York state courts, effectively none of these motions have been successful. Most have been tossed out before the history of the law is even considered. State court challenges to felon prohibition laws aren’t included in The Trace’s database, which is limited to federal court cases, but the state numbers likely rival those in the federal system.

Still, public defenders see challenging the felon gun ban as a chance to give their clients a fairer shot.

“When you’re starved, even a sip of water feels like a gallon, right?” Smith said. “I’m in a position here as a public defender, as a Black public defender: America decided that gun rights are a fundamental right. We didn’t get a say in that. So, what do we do? I’m not willing to settle for mass incarceration.”

Back to the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court has tried to resolve the confusion surrounding Bruen. In United States v. Rahimi, decided in June, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the “principles” in the nation’s history and tradition of regulating firearms are more important than a precise overlap with old law. Those principles, he added, show that “when an individual poses a clear threat of physical violence to another, the threatening individual may be disarmed.”

But the Rahimi ruling left many unanswered questions, and The Trace’s review shows that lower courts have continued to diverge on whether the felon gun ban is constitutional.

Andrew Willinger, the executive director of the Duke Center for Firearms Law, said it remains unclear whether banning gun possession among entire categories of people — like people with felonies — is constitutional, particularly when their convictions were for nonviolent offenses that posed no obvious danger to the public.

“You’re really talking about categorical group determinations, rather than any kind of individualized finding of a threat of danger,” Willinger said. “And Rahimi doesn’t endorse [categorical prohibitions], but it also doesn’t rule them out, right?”

The Trace’s review found that when weighing the felon gun ban, judges have distinguished between violent and nonviolent offenses. But Groban, the former prosecutor, said drawing that line is difficult.

“Who’s dangerous? What is your definition of dangerous?” Groban said. She pointed to people who have been convicted of a felony DUI, an offense that may be considered dangerous. “It’s easier to have a bright line. But that bright line is gone.”

The 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals found the felon gun ban unconstitutional in a 2023 case involving a man with a previous conviction for food stamp fraud. The Supreme Court vacated the opinion and sent the case back to the 3rd Circuit for more proceedings in light of Rahimi.

Other appeals courts, including the 8th and 11th circuits, have found the ban constitutional, effectively foreclosing challenges to the statute in their respective lower courts.

More recently, in August, the 6th Circuit upheld the felon gun ban, but appeared to limit its reach, writing that only people with felony convictions who are shown to be “dangerous” can be disarmed. The opinion’s author is an influential Trump appointee. As a result, some experts believe the ruling may hold more sway should the felon gun ban be evaluated by the Supreme Court.

It’s unclear how the justices would rule on the felon gun ban. At least one, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, wrote a dissent supporting the restoration of gun rights to nonviolent felons while she was an appeals judge for the 7th Circuit.

“That is probably the direction that the Supreme Court is headed if and when it takes up these cases,” Willinger said, “which I think it probably has to do at some point in the near future.”

Editor’s Note: The Trace’s Bruen database builds upon work by Pepperdine Law professor Jake Charles, who compiled a year’s worth of Bruen-based rulings in Second Amendment cases from June 2022 to June 2023. The Trace recreated Charles’s work for that period, added data points, and continued to expand the database with new cases up to the present day.