On June 23, 2022, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, marking a seismic shift in the landscape of American gun rights.

While the decision struck down a portion of New York’s restrictive, century-old concealed carry law, its implications extended far beyond the Empire State — and the issue of concealed carry.

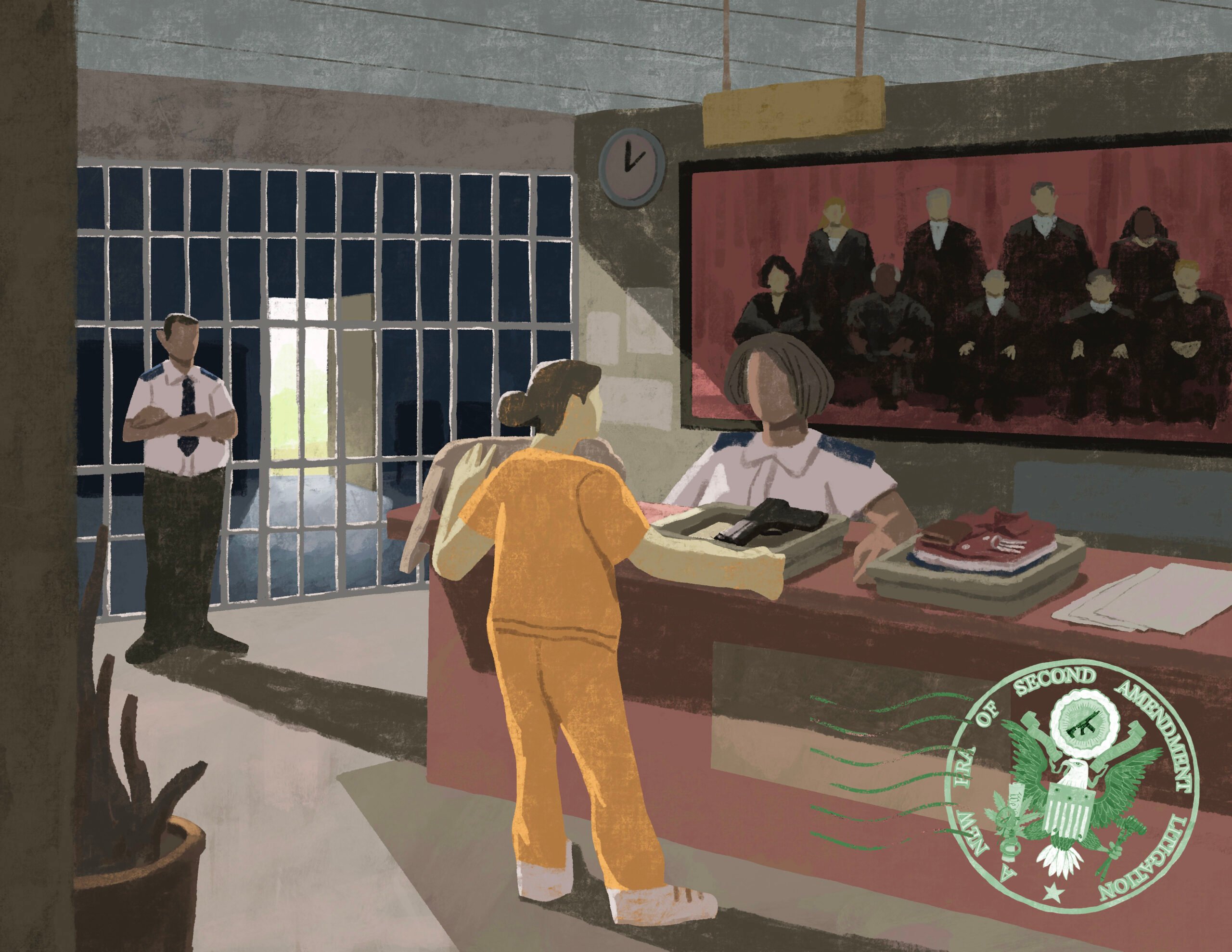

The Trace has amassed a database of more than 1,600 federal court decisions on Second Amendment challenges that cited Bruen over the past two years, and on September 12, we began rolling out a series of stories exploring the ruling’s wide-ranging effects. The first story looks at how people with felony convictions are using Bruen to challenge the ban on them possessing guns, straining the court system and raising public safety concerns.

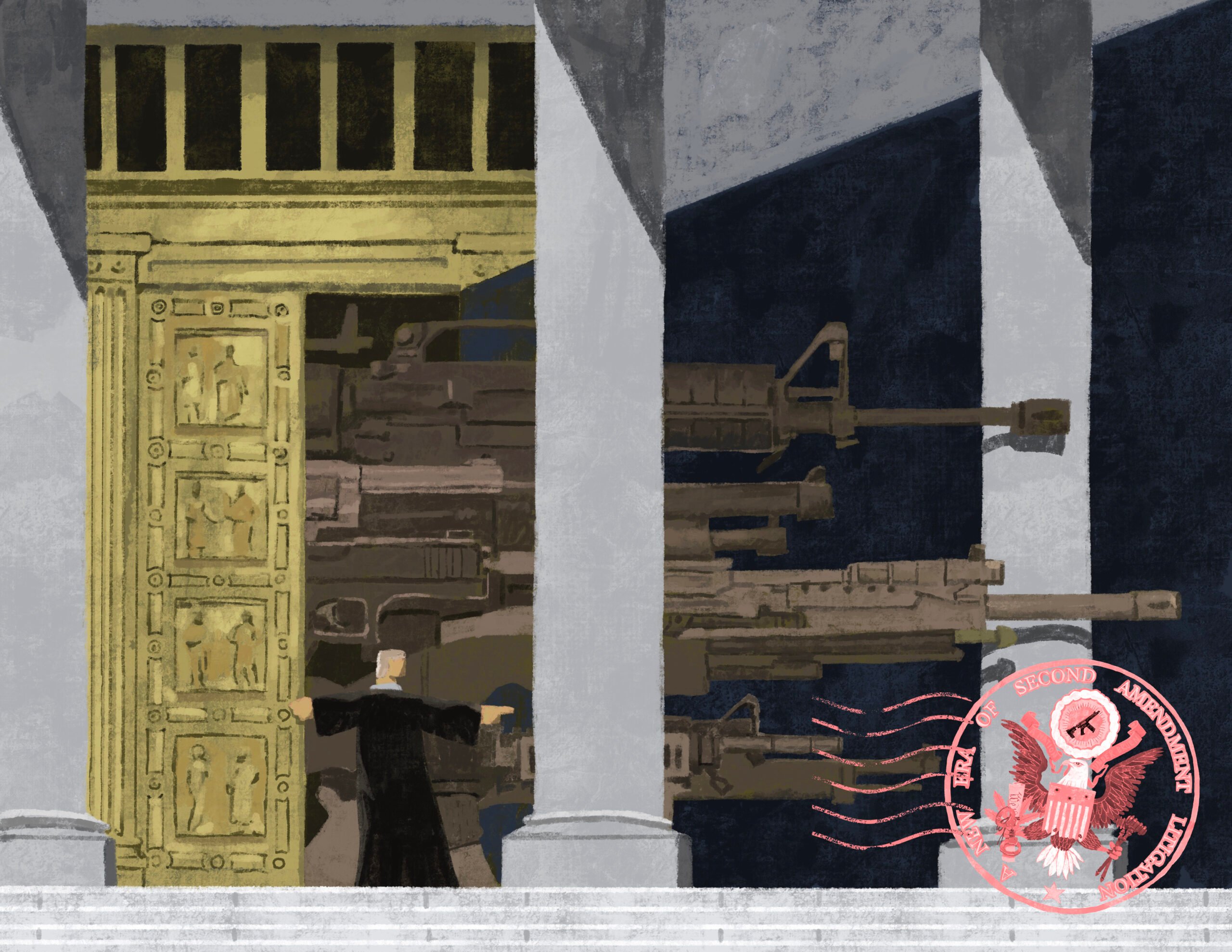

The Bruen decision recognized, for the first time, an individual right to carry a loaded gun in public for self-defense. More consequentially, the Supreme Court laid out a new test for evaluating the constitutionality of other firearm regulations.

That test has placed dozens of gun laws under threat, flooded federal courts with lawsuits, and transformed firearm regulation across the nation as lower court judges disagree on how to apply the ruling.

The Old Standard: Balancing Rights and Public Safety

In its 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller decision, the Supreme Court endorsed an individual right to possess firearms in the home. The years that followed saw lower courts coalesce around a two-step test that allowed judges to weigh gun laws against the government’s interest in promoting public safety.

In the first part of the test, a judge evaluated gun regulations by considering history, tradition, and the text of the Second Amendment to determine whether the amendment applied at all. If the judge found that it did, they would then determine whether the restriction was tailored to serve a public interest, like reducing gun violence.

Other constitutional rights are evaluated similarly: They can be limited if the limitation is narrow enough and for a good reason.

Though the 2008 and 2010 decisions triggered a wave of lawsuits, judges upheld nearly every gun law that was challenged, as courts balanced individual rights against the need to reduce gun violence and protect the public.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

The New Standard: A Historical Test

The 6-3 Bruen decision, authored by conservative Justice Clarence Thomas, threw out the second half of that two-part test as “one step too many.”

The Supreme Court declared that any regulation affecting the right to bear arms must be rooted in the “historical tradition of firearm regulation” in the United States.

Judges must still determine whether the Second Amendment applies, but modern-day concerns — the efficacy of a law in preventing crime, technological changes to firearms themselves, or rising rates of gun death — are no longer relevant. Now, for a gun restriction to be constitutional, it must have a historical analog.

Bruen has become a significant challenge for federal, state, and local governments, whose lawyers need to comb through historical records to justify modern regulations. Judges, too, have questioned whether they need to hire outside historical experts or rely solely on the evidence provided by the government or the parties challenging the gun laws.

The Direct Implications

Bruen’s first effects were felt in the half-dozen states where, like in New York, authorities had broad discretion in issuing concealed carry permits. California, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and other states rewrote their laws, requiring authorities to issue permits to any applicants who meet certain qualifications.

Despite the change, New York and some of the other states are still battling with gun rights groups in court. And while the Supreme Court generally endorsed permit requirements as constitutional, it left the door open for future challenges, particularly if the permitting process involves long delays or high fees.

The Broader Effects

Bruen cast doubt on any gun law upheld as constitutional under the old two-part test. As a result, nearly every significant gun law has faced a new challenge, and the legal landscape surrounding guns has grown increasingly volatile across the country as federal courts grapple with the surge in cases.

Hundreds of criminal defendants have cited Bruen in attempts to overturn their convictions or dismiss charges, challenging gun bans for people convicted of felonies, users of illegal drugs, and people subject to domestic violence restraining orders.

In civil cases, gun rights groups have challenged Extreme Risk Protection Order laws — also known as red flag laws — concealed carry restrictions, bans on guns in sensitive places like parks and government buildings, and limitations on assault weapons and high-capacity ammunition magazines.

The outcomes have been far less consistent than before, largely because the Bruen test leaves much open for interpretation — history and tradition are rarely agreed upon, even by historians.

Judges have disagreed on whether assault weapons qualify as “arms” under the Second Amendment, and whether convicted felons are part of the “the people” protected by it.

Moreover, it’s not enough for a law to be longstanding. (New York’s concealed carry law was enacted in 1911.) The Supreme Court said present-day laws need to be “relevantly similar” to regulations in place when the Second Amendment was ratified in 1791, or at the latest, by the time the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868. Which period is most applicable is up for debate.

Judges are also divided over exactly how similar the historical analogs need to be. For some judges, Founding Era laws that disarmed “distrusted” groups — like “Loyalists, Native Americans, Quakers, Catholics, and Blacks” — justify modern-day gun prohibitions on people who use illegal drugs or have committed nonviolent felonies.

But other judges have reached different conclusions, ruling that current laws are too substantially different in “how” and “why” they limit gun rights, or for whom, to be constitutional.

The burden of proving that a law is rooted in tradition falls to the government. If it can’t show that a regulation has a historical counterpart, that regulation is presumed to be unconstitutional. While most of the claims have been unsuccessful, challengers have succeeded in dozens of cases — far more often than before Bruen. This legal onslaught is pushing the boundaries of the new test and raising questions about the future of gun regulation in the United States.