When a Butler Township police officer responded to reports of a gunman atop a roof outside former President Donald Trump’s Pennsylvania campaign rally on July 13, he met a threat he was ill-equipped to counter: an AR-15-style rifle.

The officer quickly retreated, falling down the ladder he had used to climb to the roof, according to news reports. The gunman, perched just 150 yards away from Trump, then opened fire, wounding the former president, killing one rallygoer, and injuring two others before U.S. Secret Service snipers shot and killed him. The security failure has prompted calls for a re-examination of the decision-making that nearly enabled the fifth presidential assassination in U.S. history.

The attempt on Trump’s life isn’t the first time an AR-15 may have deterred police from intervening in an active shooting. During the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, a gunman armed with an AR-15 stalked the halls while a Broward County Sheriff’s deputy took cover outside the building. More recently, officers in Uvalde, Texas, waited an hour for the arrival of a SWAT team rather than confront the shooter killing students with an AR-15 inside Robb Elementary School.

Shootings like these highlight how access to high-powered semiautomatic rifles like the AR-15 is fundamentally reshaping the way American police respond to lethal threats.

Officers have good reason to fear: Bullets fired from AR-15s can travel roughly 3,000 feet per second — more than twice the speed of sound — and tend to tumble through the body on impact, leaving little chance of survival. Unlike rounds from officers’ own department-issued handguns, the shots from an AR-15 can pierce many types of body armor, including those worn by street cops, who often respond first to active shooter events.

“The degree of destruction caused to the human body is radically different between a handgun and an AR-15,” said Babak Sarani, the director of trauma and acute care surgery at George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C. “That officer who peeked his head up and saw an AR-15 rifle aimed at him at point-blank range — one shot and he would literally not have his head anymore.”

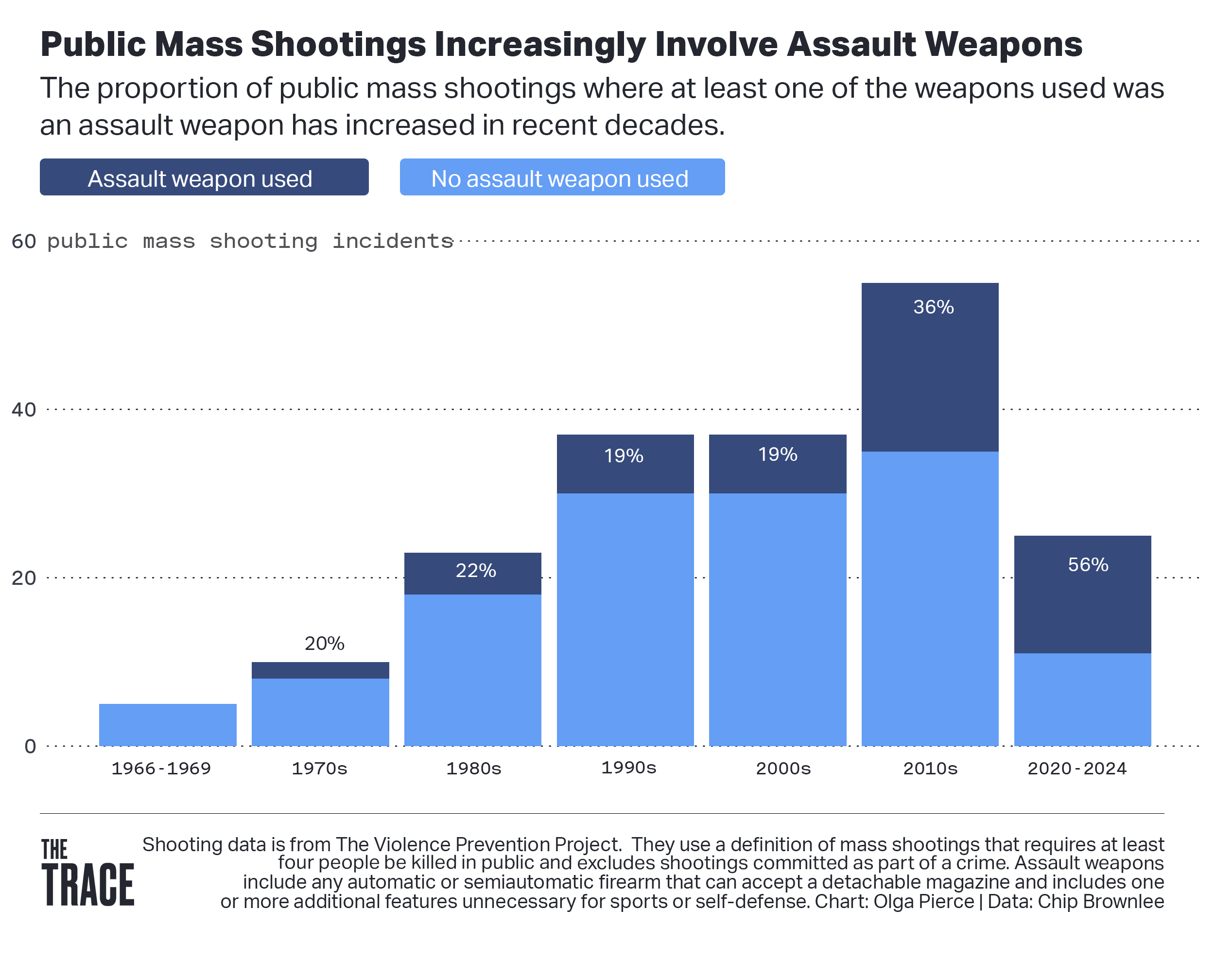

Officers are increasingly encountering AR-15s and other assault weapons at the scenes of mass shootings. Data from The Violence Prevention Project — which tracks shootings in which four or more people were killed in public — shows that during the 2000s, assault weapons were only used in about 20 percent of such events. That increased to 36 percent in the 2010s. So far in the 2020s, it is 56 percent — meaning officers responding to a public mass shooting are now more likely than not to face an AR-15 or a similar weapon.

The AR-15 is a semiautomatic version of the military’s old standard-issue rifle, the M16 — a weapon meant for combat. As a result, confronting the AR-15 remains an exceptional challenge for most local police. Despite departments increasingly equipping officers with assault weapons, officers generally carry and receive more training in the use of pistols, tasers, and batons.

Rick Vasquez, a former firearms technology expert for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, said the power of AR-15 rounds makes it difficult for officers to find cover. “A two-by-four, a mailbox, a wooden door, sheetrock — it’s not going to stop it. It’s going to go right through it,” Vasquez said. “It’s the velocity that it’s being launched at. It’s almost three times the velocity of a 9mm. That’s what gives it the penetrability and its ability to kill.”

Concerns about police being unable to effectively counter AR-15s have motivated calls to renew the federal assault weapons ban, though the logistics of such a plan are somewhat complicated by the rifle’s popularity. Assault weapons ban legislation introduced in the U.S. House and Senate would grandfather in existing assault weapons. That would leave millions of rifles in circulation, doing little to alter the calculus of officers asked to confront active shooters.

To try to address this imbalance, some police forces have increased their active shooter response training, and spent money beefing up tactical teams for deployment in high-powered confrontations. Still, in situations like the attempted assassination of former President Trump, it’s street cops that are generally capable of intervening before the first deadly shots are fired.

“As these threats, whether its terrorism, school shootings, or mass shootings, have emerged, the response has been to double down on a weapons-centered, law enforcement-centered approach,” said Alex Vitale, a sociology professor and coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College. “We can’t fix this problem by putting a cop on every street corner with a rifle and body armor. It’s too expensive. It would be a police state.”

Since the expiration of the decade-long federal assault weapons ban in 2004, sales of assault weapons have climbed exponentially, according to estimates from the National Shooting Sports Foundation, the gun industry’s trade group. The NSSF reported in January that there were more than 28 million modern sporting rifles — industry parlance for assault weapons, of which AR-15s are a subset — in circulation. The rifle is now among the most popular in the country, branded by gun groups and firearm enthusiasts as “America’s rifle.” It is highly customizable and used for both hunting and self-defense.

Experts say AR-15s are so easy to handle that even inexperienced shooters can fire accurately from hundreds of yards away.

“It’s a small bullet, which means a smaller amount of gunpowder is necessary,” said Dave Kopel, a legal scholar and Second Amendment advocate who serves as the research director at the Independence Institute, a libertarian think tank. “This substantially reduces felt recoil, which is one of the key reasons the gun is easy to shoot.”

However, what’s popular among Americans at large is also becoming a favorite among criminals. The number of guns recovered at crime scenes that were chambered for .223-, 5.56-, and 7.62-caliber ammunition — among the most popular rounds used in AR-15s and other assault weapons — surged from about 18,000 to 28,000 between 2018 and 2022, the latest year for which ATF data is available. That is an increase of more than 50 percent over a five-year span.

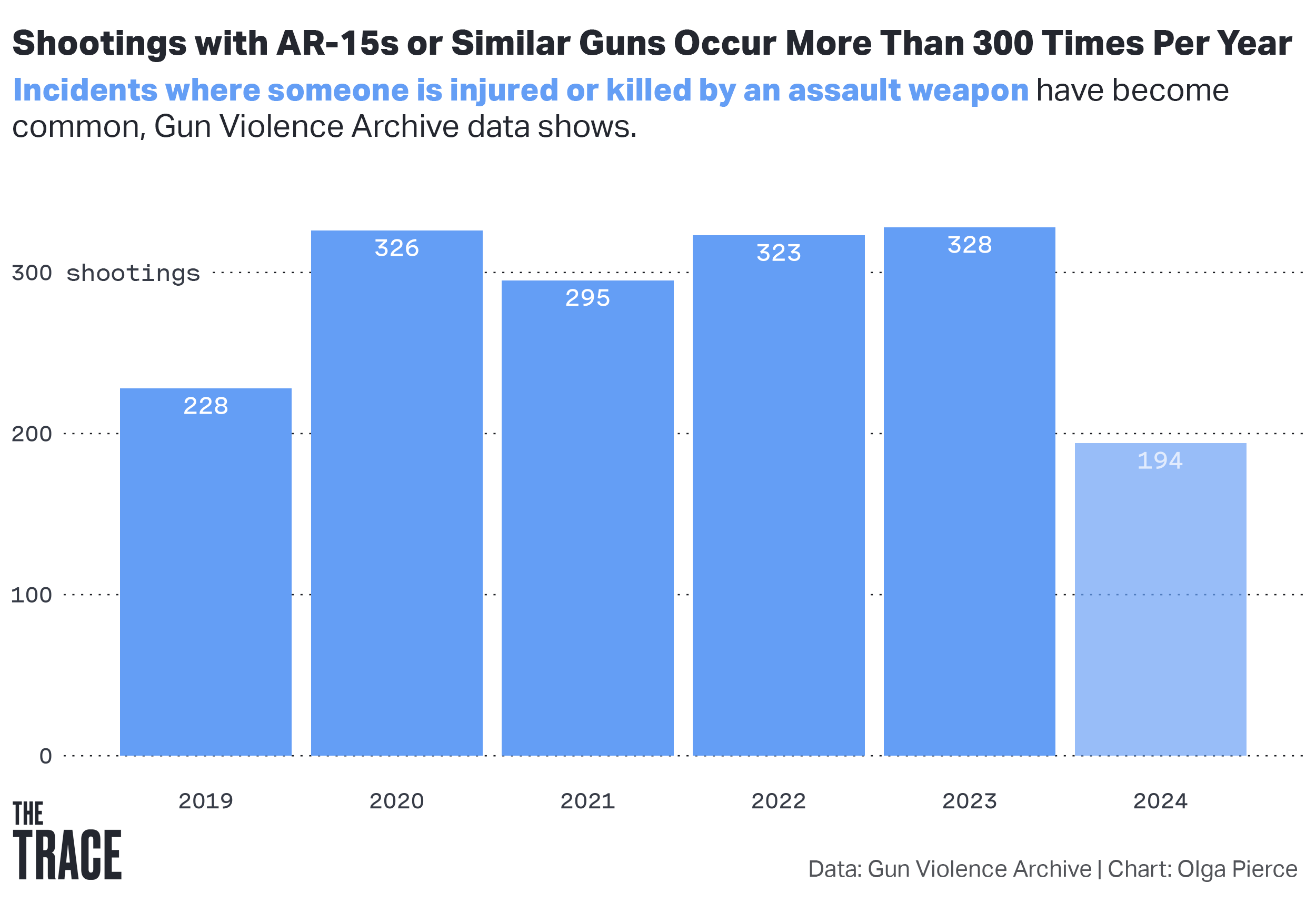

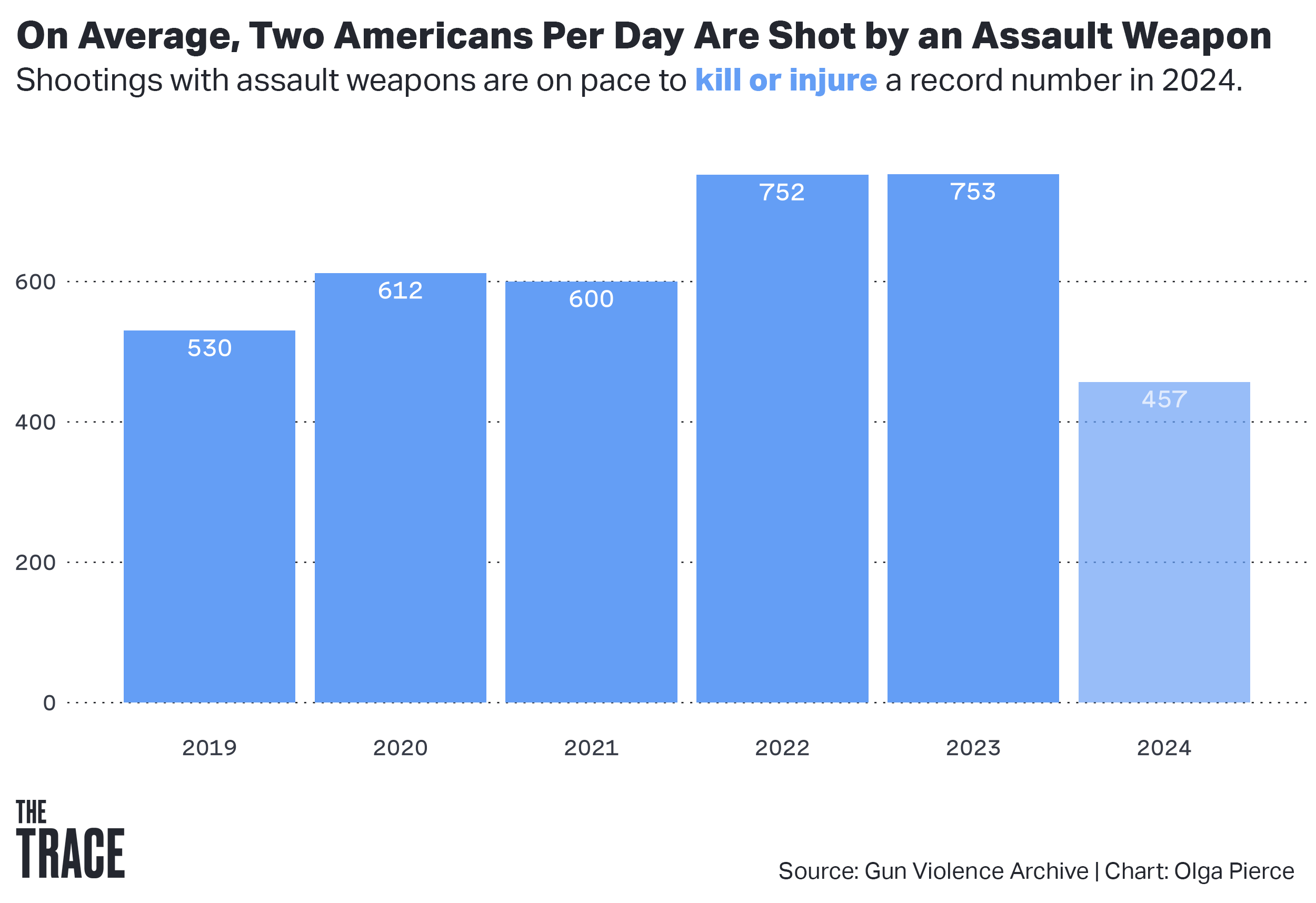

An increasing number of people have been shot with AR-15s and other assault weapons in the United States over the past five years, according to the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit that tracks shootings through media and police reports. There were 753 people injured or killed in shootings involving assault weapons in 2023, up more than 40 percent from 2019, when 530 people were shot.

Some of the victims were members of law enforcement. A New Mexico State Police officer was fatally shot in the head with an AR-15 in February 2021 when a driver he’d pulled over got out of the car and opened fire. In another case, four officers attempting to serve a warrant at a Charlotte, North Carolina, home in April died after a suspect armed with an AR-15 started shooting from a second-story window. Another four officers were wounded.

Nine states and the District of Columbia have banned assault weapons. Four — California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey — imposed the bans before the rifles became widely popular, while Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, New York, Washington, and the District of Columbia passed their legislation more recently, several in response to high-profile mass shootings. All of the bans but New Jersey’s and the District of Columbia’s allowed people who already owned assault weapons to keep them. Only California, Connecticut, Illinois, and New York require owners to register their assault weapons with state authorities.

Vitale, the sociology professor, said police will struggle to effectively respond to active shootings as long as AR-15s and other assault weapons remain widely available.

“There’s this mythic desire for a risk-free reality that is just not possible, especially in an environment that is awash with high-capacity, long-range guns, and high levels of social and political alienation,” Vitale said. “We keep doubling down on the failed strategy because no other strategy is politically viable.”

Trace reporter Chip Brownlee contributed data analysis to this story.