In the fall of 2021, Summer Tatum, a radiology technician in Prattville, Alabama, was looking forward to the birth of her first child, a boy. She had already chosen a name, Everett.

But by last October, Tatum’s young family was crumbling. She and her husband had been arguing for days over texts from another woman. At some point, her husband got ahold of her revolver. As she knelt on the floor and begged for her life, her husband shot her twice in the back of the head. Tatum died at the hospital. Everett was delivered but lived for only two hours.

Tatum, 26, lived and died in a region of the country disproportionately beset by gun violence — the rural South.

That’s according to our extensive analysis of data from the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit organization that tracks both gun injuries and deaths. The analysis shows that half of all shootings between 2014 and 2023 occurred outside large cities, in small cities and towns of fewer than 1 million people. Thirteen of the 20 towns and cities with the highest rates of shootings were located in the South, including Selma, Alabama — which had a per capita shooting rate that was higher than Chicago’s.

A person living in a community like Tatum’s is more likely to be killed or injured in a shooting than someone living in Los Angeles or Baltimore.

“People generally think of gun violence as an urban issue, but we’re learning that is not always the case,” said Shani Buggs, a community violence researcher at the University of California, Davis. “There are rural areas with higher rates of gun violence than some urban areas.”

Around the country, more than 167,000 people were fatally shot between 2014 and 2023, according to GVA data, a decade of which is available for the first time. That’s nearly twice the number of American service members who have died in battle during all foreign wars since World War II. Another 324,000 people were injured by firearms. Gun deaths increased more than 50 percent and injuries increased 66 percent.

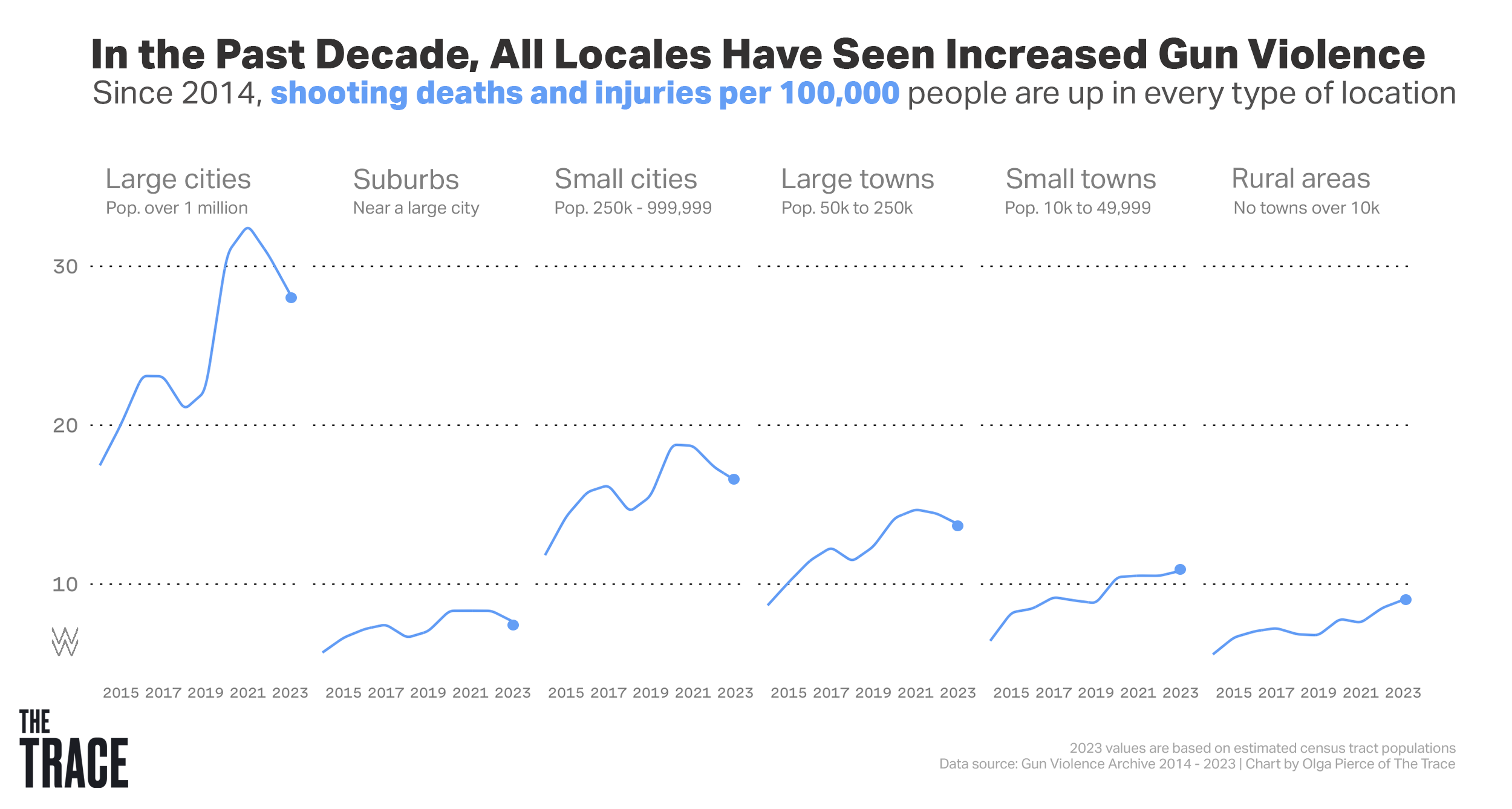

To be sure, the largest number of shootings took place in large cities, however residents of smaller places with high per capita rates experience gun violence disproportionately.

The states with the highest rates of shooting fatalities and injuries per 100,000 residents were Louisiana, Illinois, Mississippi, and Alabama. The lowest rates were in Hawaii, New Hampshire, and Maine.

The surge in shootings coincides with an unwinding of gun laws in several states. At the same time, guns have flooded the country in record numbers.

Shootings were already up from 2014 when COVID-19 struck, and then all types of locales experienced a significant spike that lasted through 2022. Larger places have seen the spike begin to subside, though gun violence mostly remains above pre-pandemic levels. In small towns and rural areas, however, rates are still going up.

The problem is worse in the South

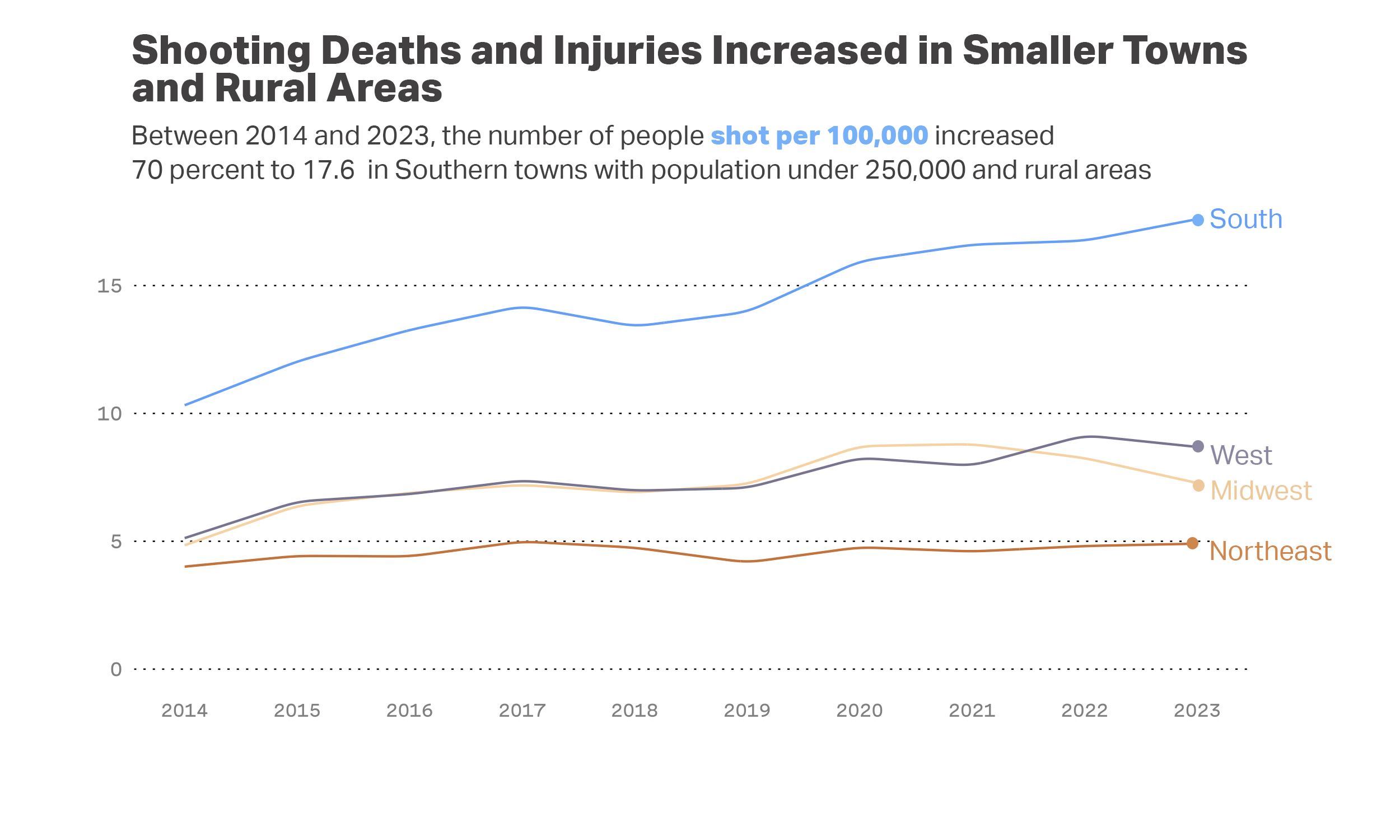

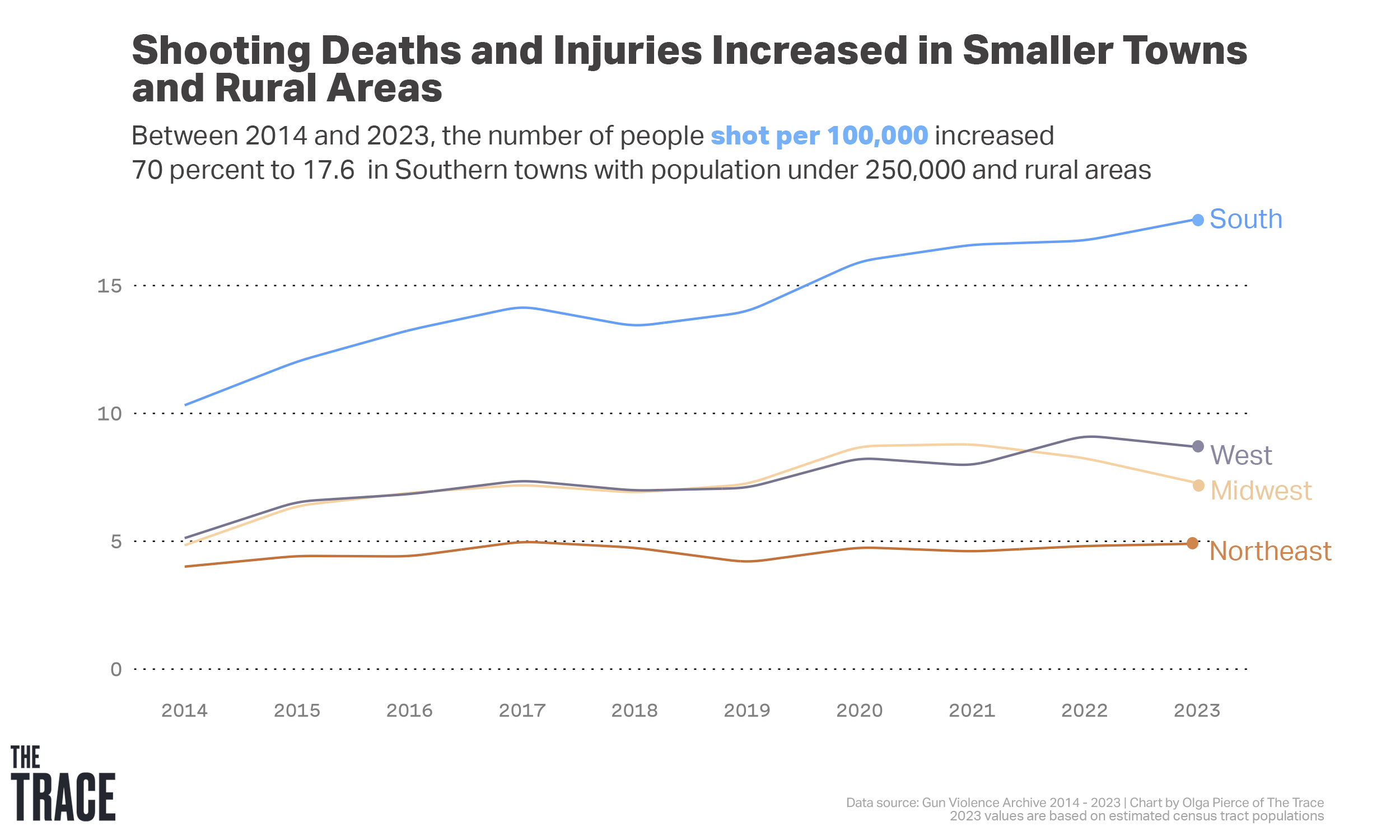

Rural areas and large and small towns in the South have much higher levels of gun violence than their counterparts in other regions. In fact, less-populous places in the South have more shootings per capita than large cities that are commonly portrayed as among the most violent in America.

Clarksdale, Mississippi; Selma, Alabama; and Laurinburg, North Carolina — each with a metro population of less than 100,000 people — were among the places that saw more people shot per capita last year than Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington.

Twelve towns and small cities in the South were among the top 20 metro areas with the most shooting victims per capita. Their rates, all of which were over 70 shooting deaths and injuries per 100,000 people, were more than six times the rate in New York City and five times the rate in Los Angeles.

Many Southern states have lax gun laws and are grappling with deeply entrenched racial segregation and the long shadow of Jim Crow. The South tends to have fewer social supports, higher rates of racial inequity, and more poverty than other regions.

Selma, Alabama — where the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., famously led a civil rights march in 1965 — had the highest rate of shooting deaths of any city anywhere last year.

“What we’ve seen in the last 10 years in the South is broadly a regression around addressing economic disparities and racial disparities,” said Buggs, the California community violence researcher, who is from Alabama. “There’s limited opportunity, there’s limited response to that limited opportunity, and so there’s just deprivation — and easy access to guns.”

It’s also bad in small cities

Alongside rural areas and towns in the South, small cities in the South and Midwest also saw high rates of gun violence compared to other regions.

In the Midwest, cities with populations between 250,000 and 1 million endured more than 18 gun deaths or injuries per 100,000 people over the last decade. Similarly sized Southern cities had a rate of more than 20 per 100,000. During the same period, these cities in the South and Midwest had rates of gun violence nearly twice that of similarly sized cities in the West and Northeast.

Reggie Moore, the violence prevention policy and engagement director at the Medical College of Wisconsin’s Comprehensive Injury Center, says many shootings in Milwaukee, Indianapolis, and other Midwestern cities are acts of retaliation among groups of young people who have lost friends to violence. “They’re not organized, traditional street organizations. It’s not drugs,” Moore said. “It’s pain, disrespect, and rage combined in young people between the ages of 13 and 24.”

In Peoria, Illinois — a city made famous by Abraham Lincoln, who gave a speech there in 1854 — rates of gun death and injury more than doubled from 14.5 in 2014 to 37.2 in 2023 per 100,000 people, our analysis found.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

After a 2023 shootout on a public street, the police chief blamed the city’s spike in violence on conflicts between groups of teenagers. He urged parents to keep a close eye on their children, and activities were canceled at some schools.

In November, Peoria Community Against Violence, an organization that for nine years had provided assistance to shooting victims, was forced to close its doors. The Peoria County coroner, who had referred victims and their families to PCAV, told a local news station that it was now unclear who would offer them emergency support.

In Wichita, Kansas, the number of people killed and injured per capita each year increased by 60 percent between 2014 and 2023, from 14.3 to 22.7.

In 2022, after a single weekend that saw 10 shootings, including one in which a teenager was killed at a graduation party, City Councilman Brandon Johnson begged the community for help. “I’m here because I am tired of seeing our young people die,” he said. “Guns do not have to be the answer.”

The Wichita Police Department attributed the high number of shootings to domestic violence. Advocates said economic stress and a lack of available assistance had led to a 60 percent increase in domestic violence shelter stays last year.

So what is the story of gun violence in America over the past decade?

Regardless of whether you live in a small town or a large city, if gun violence feels like it’s gotten worse over the past decade, that’s because it has. Between 2014 and 2023, shootings went up 40 to 60 percent in cities, 60 to 70 percent in small towns and rural areas, and 30 percent in suburbs.

All types of gun violence rose over the past decade. Mass shootings — which GVA defines as incidents in which four or more people were shot — more than doubled between 2014 and 2023. (While they’re the most visible manifestation of American gun violence, mass shootings account for less than 5 percent of the nation’s gun violence toll.)

That nearly one out of every two shootings we analyzed took place outside of large metro areas undermines the notion that gun violence is a big-city problem.

As The Trace has previously reported, gun violence victims are often overlooked in less-populated areas and policymakers can reject measures that would help the situation under the mistaken assumption that the problem doesn’t exist there.

“This is everybody’s problem,” said Charles Branas, the chair of epidemiology at Columbia University’s School of Public Health. “We all need to get together on the issue if we really are going to make a difference.”

The data used in this story was assembled through a thorough analysis. Read our methodology here.

Clarification: This article was updated to specify that the number of American service members who have died in foreign wars refers exclusively to battle deaths and does not include other categories of military-related fatalities.