Michelle Pratchet can’t remember the last time she heard gunshots. The newfound quiet is a welcome change for the 54-year-old, who was born and raised in Gary, Indiana, a city often stigmatized for its history of violence.

“I just look at it like this,” she said. “Wherever you live, you have to make the best of it.”

Pratchet’s experience reflects an encouraging trend in Gary. In 2023, the city recorded 52 homicides, a 13 percent decrease from the previous year, according to the Gary Police Department.

Community organizers, law enforcement, and local activists have united to disrupt cycles of violence once ubiquitous here, reclaiming their city as they do the work. They point to the positive impact of violence prevention programs established to target gun violence in particular over a decade ago — some of which went dormant during the pandemic — and newer anti-violence initiatives that are gaining momentum. These stakeholders have held community forums, organized fundraisers and anti-violence basketball games, and formed coalitions to encourage interaction between police and residents.

“The police alone aren’t going to solve the problem,” said Chuck Hughes, a lifelong resident and former city council member who heads the Gary Chamber of Commerce. “The mayor isn’t going to solve the problem. It does take everybody, and it takes everybody supporting the people whose primary responsibility is to make a city safe.

“It’s going to take a groundswell. All hands on deck.”

Few people are as dedicated to curbing violence in the city as 23-year-old Aaliyah Stewart, who understands the repercussions of gun violence firsthand. When she was 7, she lost her older brother in a shooting outside a Gary gas station — he was 16. Six years later, her other brother was also fatally shot at age 20, leaving her an only child.

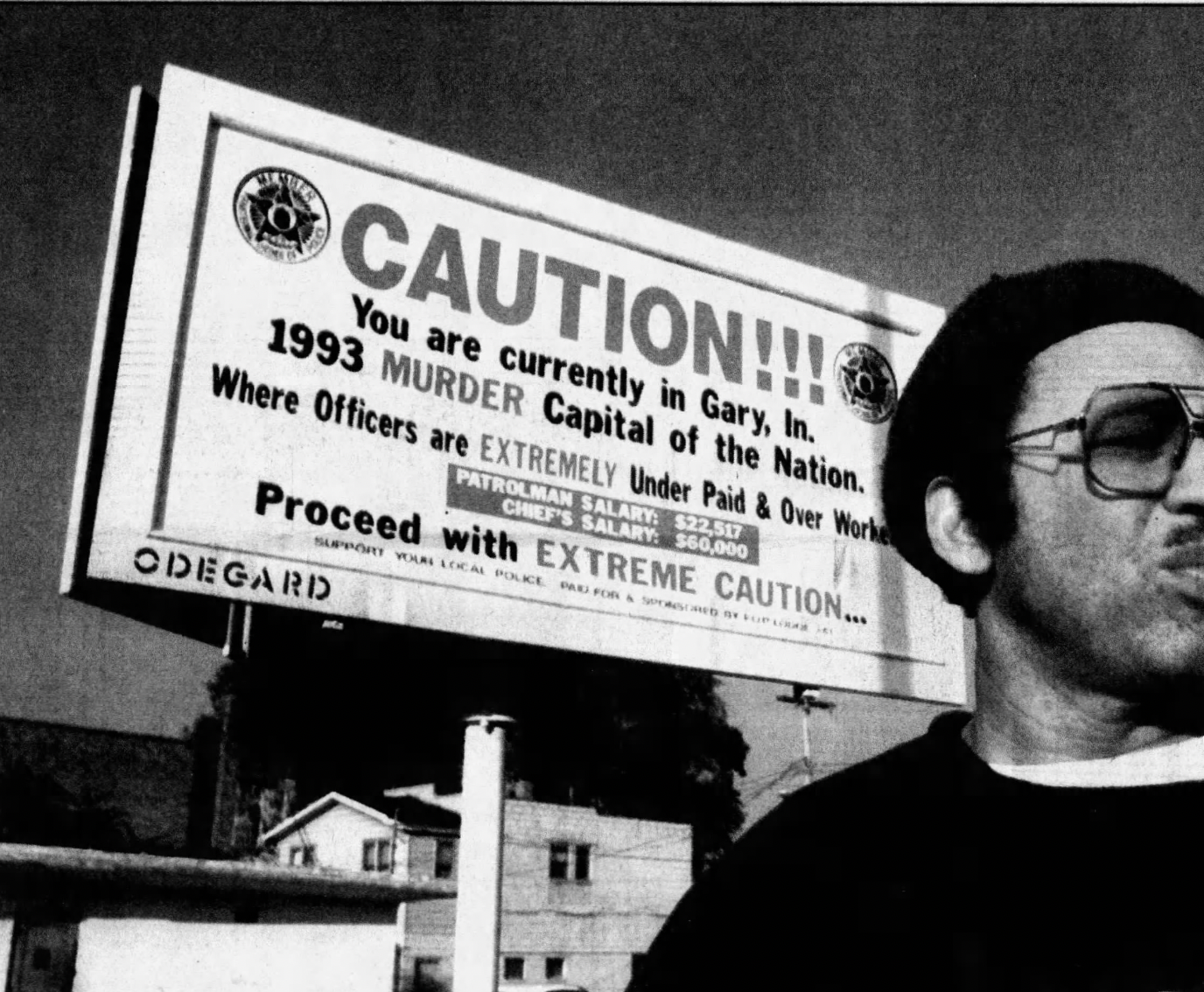

Nearly a decade earlier, in the mid-1990s, drivers along Gary’s Broadway Avenue were greeted by a grave warning: a billboard declaring, in bold red letters, “CAUTION!!! You are currently in Gary, In. 1993 MURDER Capital of the Nation … Proceed with EXTREME CAUTION.” At the time, Gary was home to roughly 119,000 people, and endured 110 killings; its murder rate was 91 per 100,000 people, almost 10 times the national average. The city’s violence underscored deeper issues rooted in Gary’s dramatic shift from industrial prosperity to economic hardship.

A former boomtown of the early 20th century, Gary reached its industrial peak in the 1970s, when the Gary Steel Mill employed 30,000 people. For the city’s Black residents, who made up 70% of the population, those jobs were ladders to the middle class. Within two decades, however, the workforce dwindled to 6,000 amid the erosion of the American steel industry, and the city’s resulting economic downturn led to white flight and increases in poverty and crime.

“Certainly, the white flight and business disinvestment that occurred in the 1960s changed the city,” said James B. Lane, an emeritus history professor at Indiana University Northwest. “At this time, the civil rights movement was gaining steam, and white fear caused people to leave, which played a major role in the declining population of Gary and the collapse of the commercial district.”

The combination of systemic racism, decline in industry, and economic challenges can engender conditions ripe for violence, said Storm Ervin, a researcher at the Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center, “especially in the Midwest.”

The decline in financial fortunes brought unique challenges to Gary, including a grim moniker that would be difficult to shake for years to come: “murder capital.” The label was printed in headlines nationwide, making Gary infamous across the country but also leaving an indelible mark on those who lived in it, shaping the city’s identity and often overshadowing its rich history.

“I think that a lot of the stigma that we received is because we were a Black city,” said Hughes, the former council member and current chamber of commerce president. “There are plenty of other cities that have been labeled the murder capital annually, but because they have garden spots and vacation areas, they don’t get branded like that.”

Stewart, who lost both her brothers to gun violence, transformed her grief into action. She emerged as one of the dozens of key leaders in the city working to forge a brighter future for the city by starting the nonprofit I Am Them Foundation, to advocate against gun violence, when she was a high school freshman. One of the foundation’s early initiatives awarded $500 scholarships to students who wrote essays about what they would do to stop violence in their community. I Am Them has since extended its impact through an annual toy drive that gives hundreds of toys to children and teens every year.

“I think that gun violence as a whole will decrease once we find positive ways for young people to express themselves and to get out,” Stewart said. “I believe it will become better and easier for young kids to find new ways.”

Last December, former Police Chief Anthony Titus proudly showcased one of the Gary Police Department’s latest advancements: a high-technology crime center, opened two months before to bolster the city’s crime-fighting efforts.

Over 1,400 residents and 500 businesses share camera feeds with the department through its Operation Safe Zone initiative, launched in 2022. The collaboration allows the department to monitor police body cameras, license plate readers, shot detectors, and security cameras all in real time, giving officers better monitoring capabilities and incident response times.

It’s “another set of eyes” for the department, Titus said of the initiative.

While the center’s innovation has supported the GPD’s crime-fighting efforts, Titus emphasized that it’s the department’s community-oriented approach that has been a critical factor in the decline of homicides. As leader of the Gary Police Department from July to December 2023, he said he prioritized interacting with community members and increasing officers’ visibility by routinely patrolling areas most susceptible to crime, like parks, large businesses, and abandoned buildings. But he also made a point to engage with “every community organization that’s doing good in the city.”

By embracing events like Coffee with a Cop and National Night Out, which introduced residents to law enforcement officials, Titus said the police have been able to combat crime and simultaneously help to change the narrative about his hometown and policing. “We’re trying to make sure that citizens’ concerns aren’t falling on deaf ears.”

Other residents emphasized that their memories of living in Gary contradicted the city’s reputation for violence.

“When you grow up in a community — even if there is danger — if you know the people you live around and you’re part of the community, it may not feel as dangerous as it may appear to an outsider,” said Maya Etienne, a 43-year-old resident.

Local officials have created several programs focused on gun violence prevention and intervention over the years, each adopting a different approach to tackling violent crime.

“I’ve never felt unsafe in Gary,” said state Representative Ragen Hatcher, a Democrat from Gary, who recently visited the White House to discuss gun violence prevention strategy, and whose father was the first Black mayor elected in Gary. “If you ask most residents of Gary, I don’t think most people feel unsafe here.”

Gary for Life, launched in 2015 under then-Mayor Karen Freeman-Wilson, was one of the longest-running initiatives. The program assisted victims of violent crimes and suspected gang members with resources like therapy, job training, and education, steering them away from crime and toward more positive life paths.

“Even though there are some initiatives that may not be active at this point, I definitely see it moving forward in a positive direction,” said Joy Holliday, Gary for Life’s former program manager, noting the impact of outreach on community members and young people, and on declining homicide rates. “I think we’ve built a great foundation, and I think we’re actually seeing the fruit of our labor.”

With the election of Mayor Jerome Prince in 2020, Gary increased its focus to youth violence prevention. In 2021, Prince launched THRIVE Gary, a program centered on helping the city’s youth develop lifetime goals and nonviolent conflict resolution techniques. It included roundtable discussions between residents, politicians, and law enforcement known as “peace circles,” access to mental health support through the MindRight app, and more summer job opportunities.

“I never really bought into the ‘murder capital of the world’ moniker,” said Prince, who was born and raised in Gary and pledged to address the “chilling spectacle of wanton killings” when he was elected. “There was a period where Gary was extremely violent, but that existed in many urban cities across America.”

On a crisp February afternoon, Etienne walked down 21st Avenue in her Midtown neighborhood. She drifted past one of three churches on the strip, then a boarded-up structure with a picture of a hot dog painted on its facade.

Across the street, teenagers occupied a gas station. But the two corners flanking the business captured her attention: residential streets dotted with abandoned homes, Gary’s struggles evident in the peeling paint and crumbled roofs, punctuated by the remains of a half-burned house that resembled the set of a horror film. Amid the decay, Etienne still voiced her love for Gary and hope for its future.

Yet, her warm smile faded as she gestured to a lounge that closed after a fatal shooting occurred there last summer.

“Where is the valuing of life?” she asked, her voice a mix of wonder and sorrow. “Why the lack of value in Black and brown lives? Not just in our city but around the entire world?”

Residents and local leaders are not naive about Gary’s dip in homicides. They acknowledge the work that still needs to be done.

Etienne said she is glad that the city’s homicide numbers have declined, but she is unsure how to sustain positive momentum. “I don’t know what the formula is,” she said. Yet one part of the solution is clear for her: a stronger community, mutual respect, and self-worth.

“I do know that we have to know our neighbors. We have to know who we are around,” Etienne said. “And we have to value people, and we have to value ourselves.”