While the public knows the National Rifle Association chiefly as a lobbying and campaign juggernaut, the Internal Revenue Service classifies the group as a “social welfare organization” whose firearms training, recreational shooting, and hunting programs support the common good. A partner nonprofit, the NRA Foundation, awards grants to law enforcement, gun clubs, and school shooting programs that benefit the “public interest.” These less explicitly political activities have boosted the NRA brand and sustained its soft power apparatus, a diffuse network of NRA-tied entities that includes gun ranges, Boy Scouts Councils, and 4H Clubs.

That soft power has diminished significantly over the past few years.

Andrew Lander spent 13 years shaping the NRA’s standard-setting firearms training programs. The group has held a near monopoly on teaching civilians and members of law enforcement how to handle guns. Lander specialized in teaching trainers and said the number of NRA-certified instructors grew from 30,000 to 125,000 on his watch.

When he resigned from the NRA in 2018, Lander was one of at least seven employees in the training department at the gun group’s Fairfax, Virginia, headquarters. One employee trained coaches for shotgun competition, another did the same for rifle and pistol coaches. A firearms training program for women was the focus of another colleague. Today, the training department consists of one person who has Lander’s old job, he said, and an assistant.

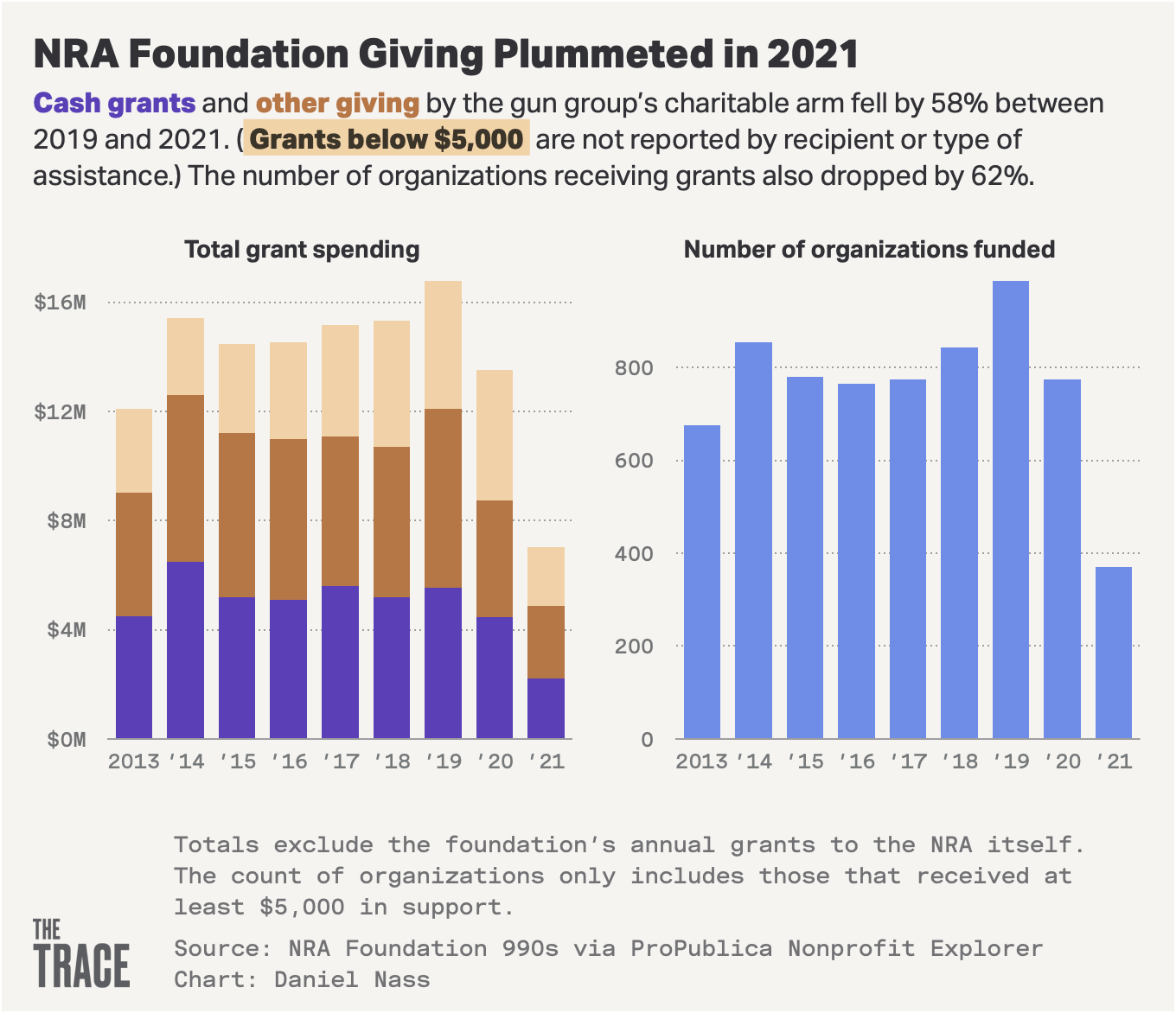

Since 2014, when it hit $13.8 million, NRA spending on education and training decreased annually to $3.2 million last year, a 77 percent drop. “I am disgusted,” Lander said.

The downsizing is due, in part, to an attempt to extract more cash from training by shifting to online courses, Lander said, but an organization-wide retrenchment and dwindling internal appreciation for the NRA’s history — the organization was founded by Union Army veterans who had concerns about the wartime marksmanship of their comrades — are also to blame.

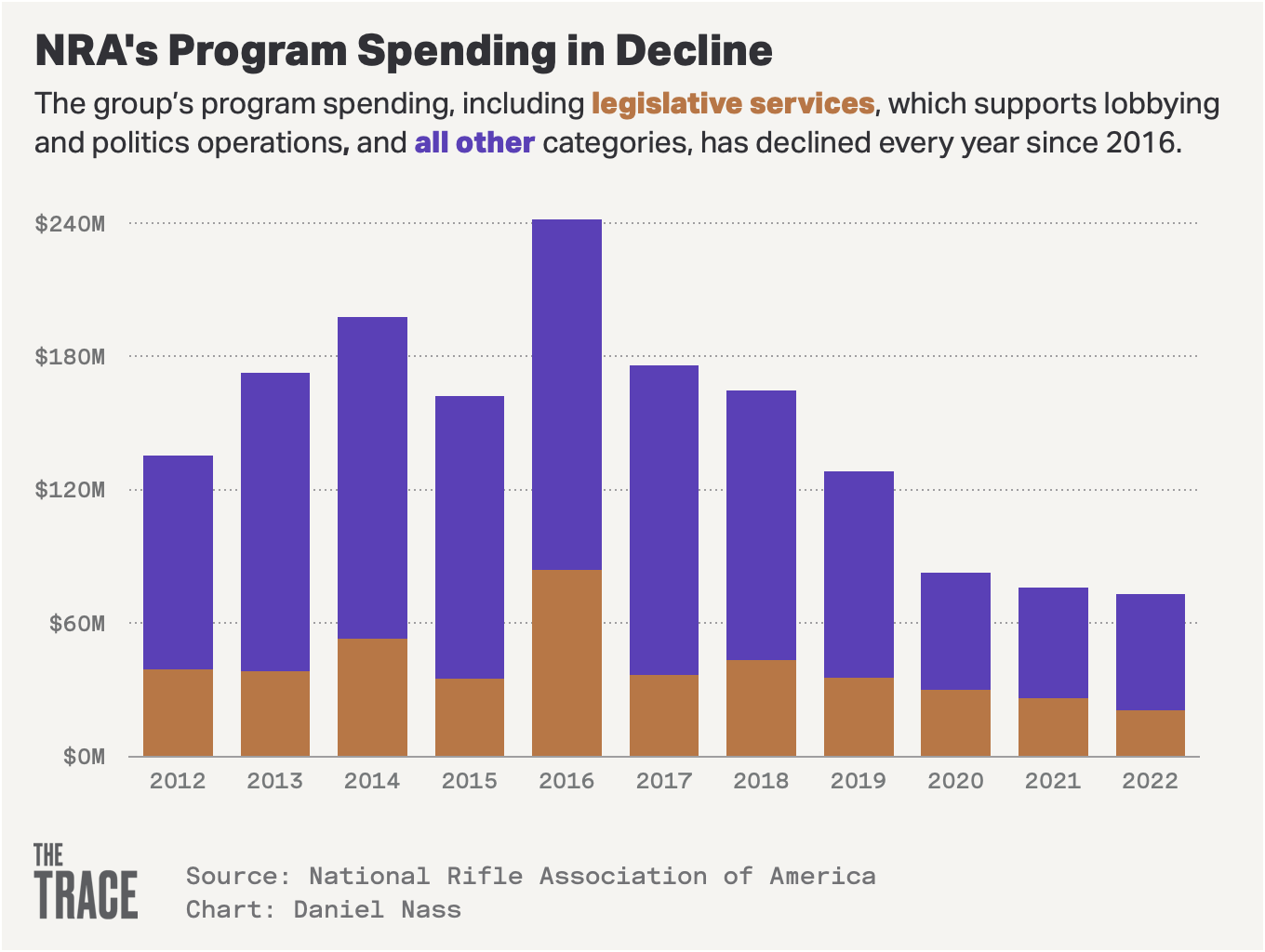

NRA program spending hit a high of $158 million in 2016 and declined annually through last year, when just $52 million was spent, a 67 percent drop, according to annual audits. (The audits list money paid to the Institute for Legislative Action, a lobbying and politics arm, under “program services.” The Trace excluded that payment from this calculation.)

NRA Foundation giving has also collapsed, going from a recent peak of $16.8 million in 2019 to $7 million in 2021, the last year for which numbers are available. (Those figures don’t include payments the foundation made directly to the NRA.) The foundation gave 370 grants of $5,000 or more in 2021 after averaging roughly 800 such grants a year for much of the last decade.

As spending declined, the NRA shed employees. The group had 521 employees in 2021, down from 912 in 2016, a 43 percent drop, IRS filings state. The paring down is evident in smaller ways too: A staff shortage closed the range at NRA headquarters one Saturday last month.

The NRA did not respond to requests for comment.

NRA-certified firearms instruction remains widely available, and the group continues to be far larger than other gun rights organizations. Yet Lander said the NRA has prioritized political aims at the expense of its fundamental mission. “I believe that the Second Amendment is a God-given right,” he said, “but with that right comes responsibility. As a responsible individual, you should seek out proper education, and that’s what the NRA has offered. But the NRA as a program-driven organization is disappearing.”

Driving the downsizing is plummeting revenue at the NRA and its foundation. Revelations about misuse of funds, many first reported by The Trace in 2019, legal battles, and the pandemic have all taken a toll. Consider just one dwindling source of cash: member dues. The NRA has seen a sharp drop in membership since 2018. In 2022, dues revenue sank to $83.3 million, the lowest amount in 16 years. By slashing programs and personnel, the NRA in 2020 and 2021 ended a four-year stretch of operating in the red. However, the group’s 2022 audit shows expenses running $15 million ahead of revenue, meaning the group once again operated at a deficit.

Brian Mittendorf is an accounting professor at The Ohio State University who has studied NRA finances and written about the group’s paring down. Mittendorf said cutting programs to bolster finances risks turning off an already shrinking membership. “When you lose resources, you lose members, and when you lose members, you lose resources,” he said. “Those things can feed on each other.” Mittendorf also noted that restricted revenue supports some programs, meaning there are limits to how deeply the NRA can trim. “At what point can you no longer cut some of these programs as a means of shoring up your finances?” he asked. “Then what happens?”

Phil Journey is a former NRA board member who has been outspoken in his criticism of the group’s current leadership. Journey has taught young people shooting as a 4H instructor in Sedgwick County, Kansas, home to Wichita, for a decade. He said that, at any given time, roughly 100 young people take part in the program, starting with BB guns and moving on to air and smallbore rifles. “They learn self-discipline,” Journey said. “They mature in so many ways that benefit them at school and in their personal lives. You can watch them grow and take responsibility.”

The Sedgwick County program is not reliant on NRA money, but other 4H shooting programs have seen their NRA Foundation funding dry up in recent years. Journey said programs “that are supposed to be at the heart of what the NRA does” have been drained to keep the organization afloat and maintain its political machine — moves that are self-defeating. “Introducing kids to shooting sports is fundamental to bringing young people into the fold,” he said. “And in 20 or 30 years, we will find ourselves in a political wilderness, without any support.”

Daniel Nass contributed to this report.