Our country would look very different without the gun industry.

And without the federal government? The gun industry might not exist at all.

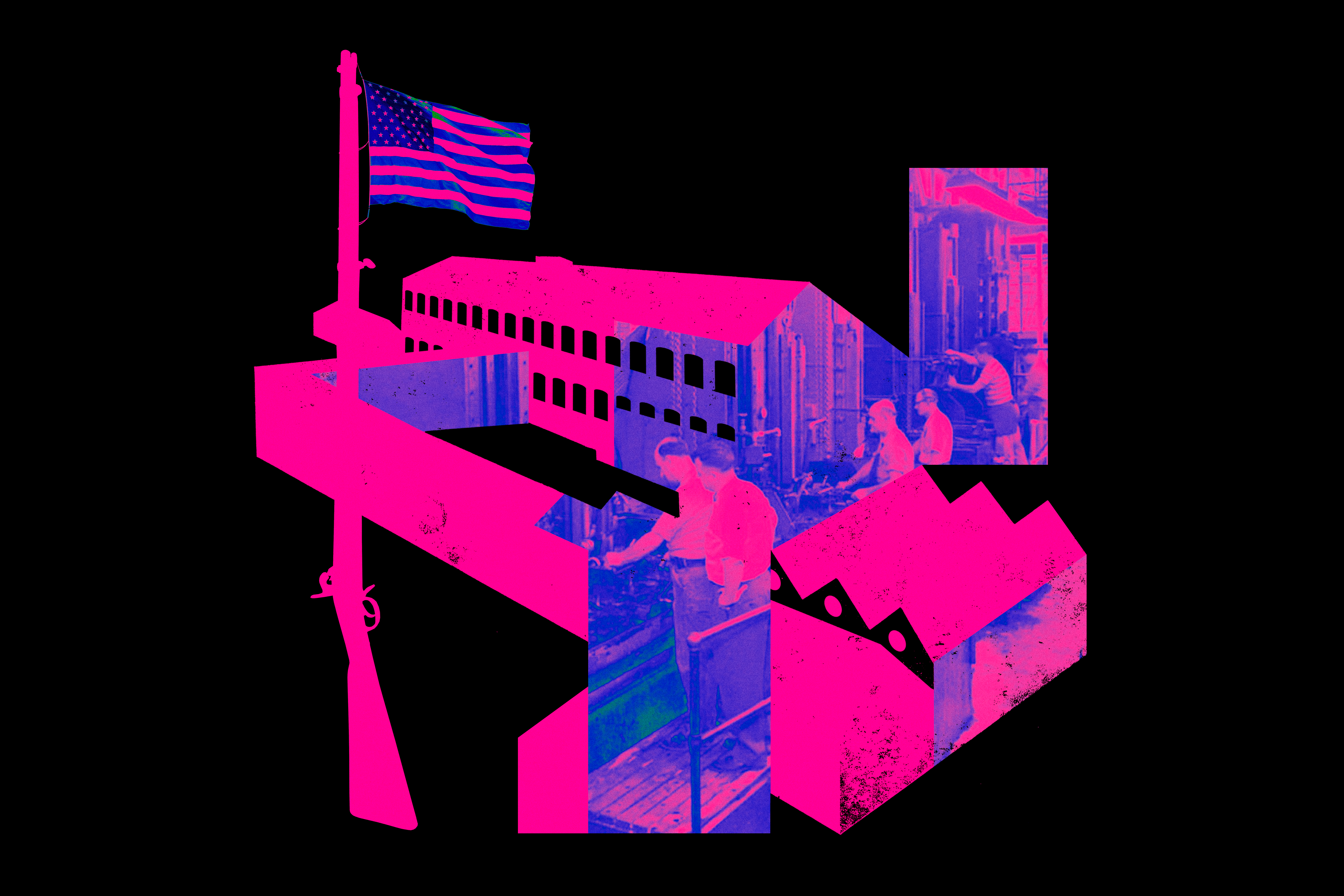

The symbiotic relationship between the gun industry and the government goes all the way back to the 1790s when the Founding Fathers created an open-source think tank in Massachusetts, the Springfield Armory. Its mission: Make the best guns in the world.

More than 200 years later, their bond is stronger than ever — even as gun rights advocates and some gun company executives invoke the government as the enemy of the industry, rather than as its biggest benefactor.

The premier episode of The Gun Machine introduces the story of how the United States has shaped, and been shaped by, the gun industry — and how we all play a role.

Follow the show on your favorite podcast app to get new episodes every Wednesday. The Gun Machine will also be available on WBUR’s site and on Here & Now from NPR and WBUR every Thursday.

Transcript

[Sound of a gun loading]

Alain Stephens: Hear that? That’s the sound of a 30-round magazine being slammed into the well of an AR-15. I’ve heard that sound thousands of times. When I think of that sound, my mind goes to a lot of places — to the military, to home. But most of all, it goes to a sprawling suburban wonderland just outside the flat-iron rock formations of the Rocky Mountains. To a place called Glendale, Colorado. You see, in 2013, Colorado was about to learn the hard way. In the wake of a mass shooting at an Aurora movie theater, the state decided it was time to ban magazines carrying over 15 rounds. So on the eve of the prohibition, a helicopter chartered by a Colorado-based gun company called Magpul Industries landed in a field where thousands of spectators stood in wait. That helicopter was full of 30-round high-capacity rifle mags — the bread-and-butter product that made the company rich. The event was the dramatic culmination of what Magpul, whose ranks included former military and law enforcement operators, called the “Boulder Airlift.” A play on the U.S.-led Cold War mission to counteract Soviet blockades in the ‘40s, the business described the effort as bringing, quote, “much-needed supplies to freedom-loving residents trapped inside occupied territory.” But really, it was just a plan to drown the state in as many soon-to-be illegal magazines as possible. And that’s exactly what it did. A video of the event shows a helicopter descending, as a man off-camera yells…

[Announcer: This … is freedom!]

Alain Stephens: This is freedom. Once the chopper touches down, staffers begin handing out magazines to the excited mob, for free. They’re even joined by gun rights media firebrand Dana Loesch.

[Dana Loesch: I follow the law. And I’ll, I’ll admit it, I own an AR-15.]

Alain Stephens: But here’s the thing. This wasn’t just a clever marketing stunt that pitted Magpul’s love of the Second Amendment against government overreach. It was a message.

And if you squint hard and think about it, you’ve seen it before.

[Charlton Heston: From my cold dead hands!]

Alain Stephens: The NRA’s Charlton Heston said it best, right? Give me liberty or give me death. Come and take it. Molon labe. For decades we’ve been told that the gun industry and the government are bitter rivals, mortal enemies, sworn adversaries. According to this story, Magpul was just the latest casualty in the war on the Second Amendment. But this story, it’s a lie. And I can prove it.

[Music]

Alain Stephens: My name is Alain Stephens, and this is my world. I’ve been in the military, I’ve worked in law enforcement, and I’ve run a ton of weaponry. Now, I’m an investigative reporter, covering what I call the “heavy metal beat.” That’s all things gun, all the time. Not just the political stunts, or the shootings that make the evening news, but what goes on behind the scenes: the people, the systems, the missing pieces of America’s bullet-ridden and bloody epidemic. And we’ll talk all about that. But first, let’s talk about violence. … The violence you know.

[Police dispatcher: 911. What is your emergency?

Caller: Yes, I just got a call from Douglas High School. Um, a female on the line (inaudible) if there is a shooter at the school.]

Alain Stephens: In my line of work, we call this the mass shooting cycle.

[Police dispatcher: 315 and 314, there is at least one person that’s been shot. But they’re saying there’s…]

Alain Stephens: We call it a cycle because we see the same thing over and over again. Step one: We ID a shooter.

[Caller: They called the dispatcher and all the lines were busy.

Police dispatcher: Listen, listen, ma’am, ma’am. The phones have rolled over to the sheriff’s office. They’ve got multiple officers…]

Alain Stephens: Step two: The media floods in and extracts the pain.

[Montage of news anchors reporting on mass shooting]

Alain Stephens: My favorite, Step three: the dead-end arguments.

[Montage of political gun debates]

Alain Stephens: We call it a cycle because for a crime that has nearly doubled in occurrence over the last decade, no progress has been made. And this, for most Americans, is where the world of gun violence starts and stops — at the endless debate over a crime that only accounts for two percent of all gun violence victims. And while we argue, cry, and die, there is this other world. One behind the world of violence you know.

[Music]

[Montage of gun sales news clips]

Alain Stephens: That’s 132 gun deaths a day. It’s federal agents, it’s arms traffickers, and of course: the gun industry. And over my last eight years combing through American violence, I’ve been chewing on this question: What makes the gun industry? Not its bottom line or its product line, but what fundamentally makes it tick? And the answer is surprisingly simple: It’s us. And by “us,” I mean the U.S. government. Maybe you already know this. But what you don’t know is that America was built on the gun. And it’s a story that spans centuries. You’re listening to The Gun Machine: How America Was Forged by the Gun Industry. A podcast by WBUR and The Trace.

“Chapter One: The Machine We Make”

—

[Sound of a rifle firing]

Alain Stephens: This is the sound of a Springfield rifle. When people think about what the gun industry has given America, they might think about power, death, supremacy, protection. What I think about is a simple idea that revolutionized manufacturing and changed the world. An idea so ingrained in American manufacturing, most people don’t see that this idea is in the shape of a gun. This idea is called interchangeable parts. Interchangeable parts in manufacturing is the concept that when you’re making a lot of something, it helps if you make it out of identical pieces that can be replaced, or changed, or even improved without changing the whole machine. Interchangeable parts, and the gun industry, were born when America was born.

Brian DeLay: From the founding of the country, the state and the arms industry have been partners. They’ve been intertwined. The state has been the patron of the arms industry. It was true in the 1790s, in during George Washington’s presidency, and it’s true today.

Alain Stephens: Brian DeLay is a history professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and he’s been studying the overlap between the gun industry and the government for the better part of the last decade. Think about the 1700s in the Northeast: stone walls, horse-drawn carriages, farmland. And yes, guns. But old guns. And not very reliable ones. You see, way back then, there was no gun industry. If you want a gun, you have to go to a gunsmith. It’s artisan, boutique, and truly custom. And if it breaks, you probably have to return to the same guy to fix it. There’s no scale. Which is a problem when the colonists go to war against the British, because they don’t need just guns, they need military-grade guns. Guns that could survive the wear and tear of battle. And be good at killing other people.

Alain Stephens: To ensure this American experiment, we essentially go to war with the British Empire. How do we do this with a bunch of varmint muskets and, and fouling weapons?

Brian DeLay: Yeah, well that’s exactly the question that George Washington was asking in 1775: How are we possibly gonna pull this off with all of these crappy guns? Where are we gonna get the firearms that we need?

Alain Stephens: At the time, the revolutionaries sourced by smuggling, making due with weapons coming out of France.

Brian DeLay: Washington and other figures, national figures, who we might just call nationalists — Alexander Hamilton, Henry Knox — are saying in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, OK, somehow we managed to actually prevail here through, you know, a series of unlikely events. We need to be self-sufficient in war material. Leaders of the early United States understood that there was real benefit to having state-run arsenals where state employees using state-owned equipment would manufacture state-owned firearms.

Alain Stephens: But where are they going to do it? Remember, these aren’t just gun companies they are creating, they are also militarily strategic locations. Washington and the nationalists land on two places. One site is Harper’s Ferry, which at this time is in Virginia, because George Washington is from Virginia and can make money by setting up an armory there. Yeah. Even back then, it’s the same story as today — rich white dudes claiming to help the country, but lining their pockets at the same time.

[Alain Stephens: So we are at Springfield Armory, which is essentially where America’s gun industry began.]

Alain Stephens: But the other location is Springfield, Massachusetts. Nestled in a river valley, with rich farmland, the location provided a number of tactical advantages. It’s at the meeting point of four rivers; it’s a midpoint between a bunch of other cities: Boston to the east, Albany and Montreal to the north, and New York to the South.

[Alain Stephens: If I had to explain it, it looks like a 19th century military garrison or barracks. And it’s really nice now, it’s like a place where…]

Alain Stephens: And it’s here where this new government sets up, not just a national armory, but something conceptually much bigger — a think tank. A hub of inventors, developers, businessmen, and sometimes straight up mad scientists pointing at one thing: making sure America has the best guns possible.

[Alain Stephens: You walk into this place, there’s a sign that says, “Firearms prohibited under federal law 18 U.S.C. 930 B.” You can’t bring a gun into the armory.]

[Music]

Alain Stephens: The armory isn’t a building. In its heyday it was a full-blown campus. Back in 1794, when the Armory first opened, George Washington had this mission: He wanted the armory to be in the transformation business, transforming America away from its garbage guns.

[Kevin Sweeney: Trash and light arms. That was his expression.]

Alain Stephens: That’s Kevin Sweeney, professor emeritus at Amherst College and an expert in early firearms. He met us at Springfield Armory along with…

[Scott Gausen: Scott Gausen. I’m the education specialist for Springfield Armory National Historic Site in Springfield, Massachusetts.]

Alain Stephens: They broke down a quandary faced by the Founding Fathers. At the time, they were acutely aware of their arms disadvantage, particularly of a new technology emerging among competitors — interchangeable parts. Thomas Jefferson knew that the French were trying to perfect such a technology in their own armories. If America could do it here, it could fundamentally catch us up in the military arms race.

[Scott Gausen: If something breaks on your musket, you can’t just pull a piece out of a bin and fit it on there. You’d have to file it down to fit, or somebody’s gotta make it for you, right? And so, on an individual basis, that’s not a huge deal, but for a military, when you’re getting into thousands of these things, that’s problematic.]

Alain Stephens: It was standardization, and making interchangeable parts, that was peak innovation in the 18th-century gun world. And when America put out the call, you’d never guess what kind of business entrepreneur would come knocking.

[Newsreel: In 1781, a New England farm boy, named Eli Whitney, was beginning to make a name for himself as a manufacturer of hat pins for ladies bonnets.]

Alain Stephens: Yeah, that Eli Whitney. The Massachusetts-born inventor had recently hit a brick wall after moving down to Georgia and introducing the cotton gin — a machine so powerful it would cement an entire plantation economy in the south. But the creation had been so easily ripped off, the whole venture left Whitney on the verge of bankruptcy and in debt. So in 1797, when the government solicited proposals to make 40,000 muskets, was when Whitney won the contract.

[Kevin Sweeney: Except, uh, Whitney didn’t have any machines. I don’t think he even had many employees. It took him, what, almost a decade to finish the contract he got. He had to hire other people to do it. But he’s still often credited and, and, you know, in a sort of popular level, with inventing interchangeable parts and stuff.

Alain Stephens: I mean, this guy sounds like Elon Musk.

Kevin Sweeney: Well, there is always a bit of the scam artist among some private arms dealers…]

Alain Stephens: He got his contract paid out ahead of time before delivering anything. And there’s this infamous moment where Whitney actually gets summoned to prove his progress in front of a young United States Congress. He has to show that his guns are in fact made of interchangeable parts. He shows up with piles of musket parts and, like magic, assembles a gun in real time for the government. Everybody’s impressed. But it was all a cheap parlor trick. Whitney secretly marked parts of single weapons that would fit together in his demonstration. They did figure out interchangeable parts at the armory, though the role Whitney played in that is still up for debate. But, Whitney is just one name in a list of inventors, some successful, some not, who’d tap into this open invitation by the government.

[Kevin Sweeney: You know, everyone was aware of what everyone was doing, and to an extent the government was promoting that.]

Alain Stephens: There was Thomas Blanchard, who would create the Blanchard lathe, essentially a 19th-century 3D printer that could fashion gun stocks at metric speed. The machine would go on to be used in everything, from shoemaking to wagon wheel production.

[Scott Gausen: Every time you get a key duplicated, that process is happening in that machine when you duplicate your keys. That’s what Thomas Blanchard invented in 1822, and we’re still using it.]

Alain Stephens: And later in the armory’s history, workers would take their skills and venture off on their own. In 1852 Horace Smith, a former armory worker, joined forces with business partner Daniel Wesson and forged the iconic Smith & Wesson firearms company, armed with lessons learned on the Springfield cutting room floor. And this was all part of the plan: an open-source flow of ideas between private contractors and government workers at the armory. Springfield was very different from how we think about the weapons manufacturing industry now.

[Scott Gausen: I mean, go to Raytheon today and ask ’em to wander through their facility, right? Like, it’s not, it’s not gonna happen.]

Alain Stephens: Public-private partnerships were at the origin of the gun manufacturing industry, and the origin of the country.

[Kevin Sweeney: So, this was very important in terms of industrial production, in not just the United States, but ultimately worldwide, really.]

Alain Stephens: Take a moment and think about this. We take for granted all of the trappings of our modern life. But guns were the beginning of so much in American life. It was the gun that brought us from the artisan to the factory floor. And from man-made to machine-made. The gun did all of that. These symbiotic relationships push up America’s weapon curve astronomically, all paid for by the U.S. government. From 1794 onward, Springfield armory provided the main battle rifle for every American conflict.

[Music]

Alain Stephens: Take the famous World War II rifle, the M1 Garand. Springfield produced some 4 million before the end of the war, peaking at almost 4,000 per day. You don’t need to have been in the shit to know the M1. If you’re one of the almost 250 million people who recently played Call of Duty, you know exactly what gun I’m talking about. How it looks, and how it sounds.

[Combat from a Call of Duty video game]

Alain Stephens: But Springfield’s role as the hub of the U.S. gun industry wouldn’t last forever.

[News anchor: U.S. gun manufacturers made 187 percent more firearms in 2020 than they did just 20 years ago.]

Alain Stephens: Pretty soon, the explosion of private gun companies would spread across the country and forge a relationship with the government and citizens that is still revolving endlessly today. We’ll get into that in a minute.

[Music]

[Robert McNamara: I believe I’m correct in saying that in the past four and a half years, the Viet Cong, the Communists, have lost 89,000 men, killed in South Vietnam.]

Alain Stephens: That’s Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who, in the middle of the Vietnam War, decided that the Springfield Armory was in excess to the needs of the government. Springfield created the private industry and then the private industry eclipsed it. McNamara shuttered the armory in 1968. Around the same time, the U.S. government acquired Colt’s M16, its first-ever main battle rifle from the private market.

[M16 automatic fire]

Alain Stephens: This the sound of an M16.

[More M16 fire]

Alain Stephens: And the story of this gun starts a half century ago.

[Vietnam War combat radio chatter]

Alain Stephens: Vietnam, 1968.

[Continued radio chatter / music]

Alain Stephens: The Department of the Army sends out researchers to conduct a field survey of combat troops about the performance of their newest weapon. Based off of the AR-15 — at the time, a janky, plastic-y, and maligned weapon — the M16 was sure to have room to improve. Sure enough, nearly 2,000 soldiers and Marines reported back a list of three needed improvements: chrome-plated chambers for increased reliability; space inside the gun to store a much much-needed cleaning equipment; and most importantly, the soldiers wanted a little more oomph in the battlefield — they wanted to send more rounds down range before reloading. So the Army took the standard issue 20-round magazine and put 10 bonus rounds on top. There had been a long-running debate about whether the killing potential of guns were increased by bigger magazines. For the servicemen in the jungle wanting to dominate gun fights, the answer was clear: More bullets equaled more bodies. By the 1970s, the 30-round magazine was standard issue among all U.S. troops. By 1980, the U.S. suggested everyone in NATO use it too — introducing the 30-round standardize agreement magazine, AKA the STANAG. Do the math: Every M16, AR-15, and a laundry list of guns used by international allies, all using the same interchangeable part. The person who could tap into this market would be the dark horse of the gun industry. They’d be the Goodyear to the Model T, the Heinz ketchup to Oscar Meyer. And that dark horse … is Richard Fitzpatrick.

[Richard Fitzpatrick: So to release the bolt back, you have to do, like, a three-handed affair. You have a release for the magazine here, but it’s also, if you do weakside transition, there’s no…]

Alain Stephens: Unless you’re really into guns, you probably don’t know who Richard Fitzpatrick is. Well, he’s one of the industry’s most influential inventors of the modern age. You probably wouldn’t know anything else about him from searching online, where there’s almost no trace of him. There’s a few pictures, one with him in a cowboy hat, looking like the Marlboro man. Apparently, he’s a fan of Ayn Rand, classic guitars, the blues, and flying helicopters. And as a young man, he worked as a freelance graphic artist in England, where he grew up. But in 1988, before he would become an influential gun inventor, Richard Fitzpatrick became a jarhead.

[Advertisement: Not everyone can join this rugged team. Only special, highly qualified Marines are recommended for reconnaissance…]

Alain Stephens: Fitzpatrick was beyond just a regular Marine though. He was Force Recon. Literally special operations qualified. And these kinds of credentials probably didn’t hurt when, in the mid 1990s, Fitzpatrick left the Marines to step into the weapon accessories game. And like any good tech company founder, he’d create Magpul Industries out of his Colorado garage.

[Advertisement: Next is keeping that reliability over time after rough handling and in rough environments. This is where the PMAG really starts to shine.]

Alain Stephens: Magpul’s main offering was a series of slickly designed and innovative polymer magazines, available in a variety of colors. The first reliable, plastic, STANAG 30-round magazine to hit the market. Within a few years, they started showing up in images of Special Forces operators combating the war on terror. You probably don’t spend your time pouring over photos of guns being used in conflict zones. But you know who does? Professional shooters, soldiers, and law enforcement officers. For these early adopters, Magpul’s PMAGs were spreading like Teslas or Peletons or any other new technology that, all of a sudden, was everywhere. They became so popular that Army brass had to send out messages telling rank-and-file soldiers to stop using them, because the PMAG wasn’t approved for official use. The company that Fitzpatrick started in the back of his house grew to over 200 employees. Magpul followed a handful of tenets: Profits are not evil; annoy the establishment; and the cherry on top, innovate or die. And innovate it did. This is 2011.

[Heavy artillery fire]

Alain Stephens: Not 2011 in America, but 2011 Afghanistan. A decade into the War on Terror.

[Music]

Alain Stephens: And these are Marines, who at the time are getting tired of lugging weighty, belt-fed machine guns through the mountains of Afghanistan. In the military we say, “Pounds equals pain.” And they needed something lighter, something mobile. So the Marines launched the M27. It’s essentially a rifle built for sustained automatic fire. Think a beefed up M16: The lighter weapon could use standard issue 30-round magazines, which it could dump in under three seconds.

[Automatic fire]

Alain Stephens: In comes the dark horse — Richard Fitzpatrick and Magpul. And they have a plan to take the company’s guns from the garage all the way to the Pentagon. The company releases a line of magazines that carry 40-, 60-, and 100-plus rounds, respectively, the first of their kind to be reliable, quiet, and cost-effective enough to be adopted by the military. They’re perfect for the M27, the Marine’s new gun. These extended capacity magazines begin testing with the selected Marine units abroad. It’s a turning point for Magpul. New York investment firms begin champing at the bit. Triangle Capital and Bruckmann, Rosser, Sherrill — better known for its investments in things like Liz Lang Maternity and beachwear giant Tommy Bahama — pour millions into the company.

[Music]

Alain Stephens: It was moves like these that kept Magpul products showing up in the hands of America’s most select military and police units across the globe. And civilians chased their products, too. For a guy whose livelihood was so tied to the government, Fitzpatrick’s public persona was quite skeptical of it. At one point he announced that if police departments wanted to buy Magpul products, they were going to have to take a loyalty oath to the Second Amendment. But his relationship with the government was about to dramatically change. You see, Colorado was facing a problem.

[TV reporter: To understand the political divide here in Colorado, look no farther than here, East County Line Road in Erie.]

Alain Stephens: The state is an interesting case in the world of gun violence and politics. On one side you have this culture of firm, rugged, western sentimentality around firearms, but you also have Columbine and Aurora. It was the second one, when a guy walked into the midnight premiere of a Batman movie and killed 12 people, and wounded 58 others, when the state had had enough. Remember, that’s when lawmakers introduced the bill to ban magazines with capacities above 15 rounds, the bill that Magpul would suggest was tantamount to war.

[Music]

Alain Stephens: Magpul executives said it would be a proverbial death knell to the company and what it stood for. The proposed legislation solicited the ire of the broader gun rights community too.

[News clip: I just think that we should be able to live freely, and with guns we can protect ourselves even though it might be more dangerous. … I think it’s ridiculous. I believe that people have the right to own a gun of their choosing.]

Alain Stephens: Fitzpatrick himself would testify against the law at the state capitol in Denver. One Republican state senator would even remind lawmakers that these were the magazines used to kill Osama Bin Laden. But in the end, Democrats pushing for gun reform would prevail: HB 1224 would pass and be signed into law by Governor John Hickenlooper. And Magpul was faced with a startling conclusion — their chief product was now illegal in their own home state. So you’d think, Magpul would have one last hoorah — the Boulder Airlift — then shut down operations and cease to exist.

[Music]

Alain Stephens: Nah. Fitzpatrick is a spec ops Marine — wasn’t gonna happen.

[News anchor: Tonight we find people brazenly ignoring Colorado’s new ban on high-capacity gun magazines.]

Alain Stephens: Fitzpatrick would pull in political allies outside the state, ones the company had been courting in the lead up to the law’s passage. They’d find a partner who agreed that limiting Magpul’s innovations was an affront to our national identity — a guy who ran a state not known for government interference — Texas governor Rick Perry.

[Rick Perry: Why do we need an automobile that will drive faster than 80 miles an hour? I mean, this is America.]

[Music]

Alain Stephens: Perry would incentivise the gun company to rip up ops and set up a new HQ in the Lone Star State. And you see, while small governments like Colorado didn’t need Magpul, big government did.

[Answering machine: Thank you for calling Magpul Industries. If you know your party’s extension, you may enter it at any time. Military and law enforcement customers, press one.]

Alain Stephens: In Magpul-friendly Texas, Fitzpatrick would finally tap into that mainline of funding the company had been waiting for for all those years — the Department of Defense. After moving to Texas, the company would reap $37 million to supply the Army, Marines, and Air Force — essentially the world’s largest fighting force — with boatloads of their little bullet boxes and other weapon accessories. So yeah. A company that built its rep by annoying the establishment, and saying it was staring down the government, was in fact, taking buckets of money from the government. And if you think that what Magpul did was at all new, it’s not.

[News clips: A law cracking down on guns in Maryland is now costing the state more than 150 jobs. … New Britain based Stag Arms today announcing the company is going to Wyoming by the end of the year. … I’m on Roosevelt avenue, outside Smith and Wesson’s Springfield headquarters. As you just said, it’ll be moved down south, and it was directly a result of what they’re calling damaging proposed legislation in Massachusetts that would ban the manufacturer…]

Alain Stephens: They had only tapped into an undercurrent that has existed since the very foundation of the country. Remember how I was telling you about Vietnam and the M16? How soldiers in the jungle wanted magazines with more bullets? How years later, special forces in Afghanistan started carrying Magpul PMAGs — unofficially? And how that company then created products for the U.S. Marines to use? That’s the gun machine. Every conflict, every new service weapon, pushes private gunmakers to produce better products, and presents them with opportunities to make millions of dollars. Which brings us to today, to a world of private companies chasing the near-infinite government tax bag. So why do I tell you all this? Because there is a bleed-over effect — all this innovation has a cost. Remember when I told you I was an investigative reporter? The government might have made the industry, but it’s not the industry’s only customer. Those big boy extended capacity magazines from Magpul — the ones that had New York investors and Marine units salivating — someone else loved ‘em too: mass shooters.

[Music]

Alain Stephens: Vegas.

[News anchor: This evening, at least 58 people are dead and more than 500 injured…]

Alain Stephens: The Baton Rouge cop ambush.

[News anchor: Three police officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, have been killed.]

Alain Stephens: Parkland, Florida.

[News anchor: Seventeen people were killed.]

Alain Stephens: And right back in Colorado, with Club Q.

[News anchor: Police in Colorado say five people are dead, 25 more are wounded.]

Alain Stephens: Hell, even one would make its way to Christchurch, New Zealand.

[News anchor: What we do know is 49 people have died, and that 20 people are seriously ill.]

Alain Stephens: Our reporting found Magpul extended capacity magazines in the hands of some of the most-talked-about mass shooters in the world. But no one had ever connected the dots. And that’s the thing, we don’t see how connected it is, because it’s all around us, all the time. You don’t get Richard Fitzpatrick and Magpul without Eli Whitney and interchangeable parts. And you don’t get the 200 years of everything in between without lucrative government contracts that built an industry and made it into a beast that must be fed. You see, we want to believe the worlds of war, of government, and of gun makers, are different. But they aren’t. And America isn’t just good at it, we’re the best at it. Over the last 65 years the U.S, has acquired the largest share of the international arms trade in the entire world. We are a category unto our own. In fact, if we remove the second-largest supplier of weapons, which is Russia, then American arms deals surpass that of all other countries combined.

Brian DeLay: It’s not just that we are a global leader, or even that we are the global leader…

Alain Stephens: Back to history professor Brian DeLay.

Brian DeLay: It’s that we are the arsenal to the world.

Alain Stephens: And this matters. Because whether we know it or not, we pay for it. We pay for it all. In fact, from 2013 through 2022 the federal government awarded over at least $16.6 billion to guns and ammunition companies. That doesn’t include notoriously hard-to-track state or local subsidies, which have easily reached hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more, over the last couple of decades.

Brian DeLay: All of us are investing in guns, all the time, through our tax dollars. These very gun companies that are simultaneously pursuing and getting big state contracts at multiple levels are also bankrolling the NRA. And they are pouring money into, you know, decades-long, broad-based effort to roll back firearms restrictions on all kinds of fronts. And then they’re also turning around and they’re getting contracts for local police departments in communities that are very unhappy with the status quo about our gun laws.

Alain Stephens: So, if this relationship exists and has existed for so long, and obviously there’s this American conversation going on about guns, why don’t we talk about this part of it?

Brian DeLay: I think that most Americans unhappy with the status quo with guns and gun policy in this country, they’re angry at the NRA. They may be angry at Gun Owners of America. They’re angry at Republican politicians who consistently take a lot of money from these organizations and then vote in the ways that these organizations want, and even support legislation drafted by these organizations. And instead, I think that some of the attention does need to get refocused onto these companies, and the way that these companies are the ultimate beneficiaries of our gun culture. And the degree to which this argument that we have with one another that’s framed as an ideological argument is very much a business question as well.

Alain Stephens: So now that we understand how America built the gun, in our next episode we have to ask why.

Carol Anderson: The issue of protecting the United States of America defined as white and defined as white males with guns. And so those ideas were anathema, forbidden for Black people.

Alain Stephens: Let’s talk about America’s original sin and how America got addicted to the gun machine.

Alain Stephens: The Gun Machine is a production of WBUR in partnership with The Trace. I’m your host, Alain Stephens. If you want more on this, or any of our other episodes, you should visit the TheTrace.org/GunMachine or WBUR.org/GunMachine.

If you feel like we are telling an important story, review the show on your podcast app and fill out The Gun Machine survey at WBUR.org/survey. You can sign up for The Trace’s newsletter to find more on this reporting at TheTrace.org.

Our producer, who always has my six, is WBUR’s Grace Tatter. Our editing fellow from The Trace is Agya Aning. Orchestrating our beat drops is sound designer Emily Jankowski. Our production manager is Paul Vaitkus. Our editors are Kevin Sullivan and WBUR Podcasts executive producer Ben Brock Johnson. Additional editing from Miles Kohrman. Our WBUR managing producer is Samata Joshi. And our engagement editor at The Trace is Gracie McKenzie. Audio engineering from Tim Felten and our artwork is by Diego Mallo.

Special thanks to WBUR executive editor of news Dan Mauzy; The Trace’s executive editor Craig Hunter, WBUR chief content officer Victor Hernandez, associate director of institutional giving Nicole Leonard, director of marketing Kristen Holgerson and Jessica Coughlin of Onward and Upward media; Tali Woodward, editor-in-chief at The Trace; and Margaret Low, CEO of WBUR.

Support for the Gun Machine comes from The Joyce Foundation, a nonpartisan philanthropy that invests in racial equity and economic mobility in the Great Lakes region. For more than 25 years, Joyce has supported research, education, and policy solutions to reduce gun violence and make communities safer. To learn more, go to joycefdn.org. Additional funding provided by the Kendeda Fund.