Every year since 2013, House Democrats have introduced a bill to repeal The Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, or PLCAA, which shields the firearms industry from lawsuits over harms committed with its wares. Every year, that effort has stalled in committee, captive to political gridlock that shows little sign of waning.

But a new push led by gun reform-minded states may have found a way through the industry’s special legal immunity.

In the last year, legislators in California, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York have passed laws that require gun companies to impose “reasonable controls” on their distribution chains and more carefully monitor how and where they sell firearms. Their greater significance, however, may lie in setting the stage for governments and private citizens to sue gunmakers by exploiting a narrow exception in PLCAA. If successful, such suits could mark the first time in nearly 20 years that gun companies have faced accountability in court for careless sales practices, and reshape how the firearms industry distributes guns to the American public.

“This puts the power back in the people’s hands,” said California Assemblymember Phil Ting, who authored his state’s statute, which was signed by the governor on July 12. “For far too long victims of gun violence have only received thoughts and prayers because the entire industry has been shielded by federal law. This allows victims to get justice.”

The National Shooting Sports Foundation, the industry’s trade group, has come out in opposition to the state statutes, calling New York’s an “unconstitutional attack” on businesses. The group did not respond to a request for comment.

The laws represent a renewed effort by state and local leaders to hold the gun industry accountable for supplying a public health crisis that takes tens of thousands of lives every year. Experts also say this new tactic has a greater likelihood of being effective, a stark contrast to splashy efforts by California Governor Gavin Newsom and others modeled after a controversial Texas law that would allow private citizens to sue abortion providers.

PLCAA was conceived in response to a wave of lawsuits that sought to force gun industry reforms through the courts. In the late ‘90s and early 2000s, more than 40 municipalities across the country alleged that gun manufacturers and wholesalers had failed to responsibly monitor their distribution channels, allowing thousands of weapons to be diverted to the criminal market. These companies sold guns to retailers that they had reason to believe were breaking the law, the cities’ lawyers argued, and should have to pay for the violence-related funeral, medical, and structural expenses incurred by their negligence.

The legal strategy mirrored a successful effort to rein in the tobacco industry after major tobacco brands willfully misled the public about the dangers of smoking cigarettes, and threatened to encourage similarly drastic regulation.

Rather than fighting dozens of costly and protracted legal battles, the gun industry turned to its lobbyists. The NSSF, in concert with the National Rifle Association, pushed for a bill that would stop lawsuits against gun companies over unlawful uses of their products. In 2005, President George W. Bush signed PLCAA into law. At the time, the NRA called it “the most significant piece of pro-gun legislation in 20 years.”

Within a year of PLCAA’s passage, all but one of the lawsuits brought by cities against the gun industry were dismissed. In the ensuing years, the legislation has torpedoed most subsequent attempts to sue gunmakers for their contributions to violence.

While PLCAA provides broad legal immunity, it does come with exceptions. Lawsuits against gunmakers may proceed if the company in question violated a state statute “applicable to” the sale or marketing of firearms. Nearly all lawsuits since PLCAA’s passage have hinged on differing interpretations of the words “applicable to”: Does a commerce law that regulates commerce of all goods including firearms apply? How about a marketing statute prohibiting advertisements that promote violence?

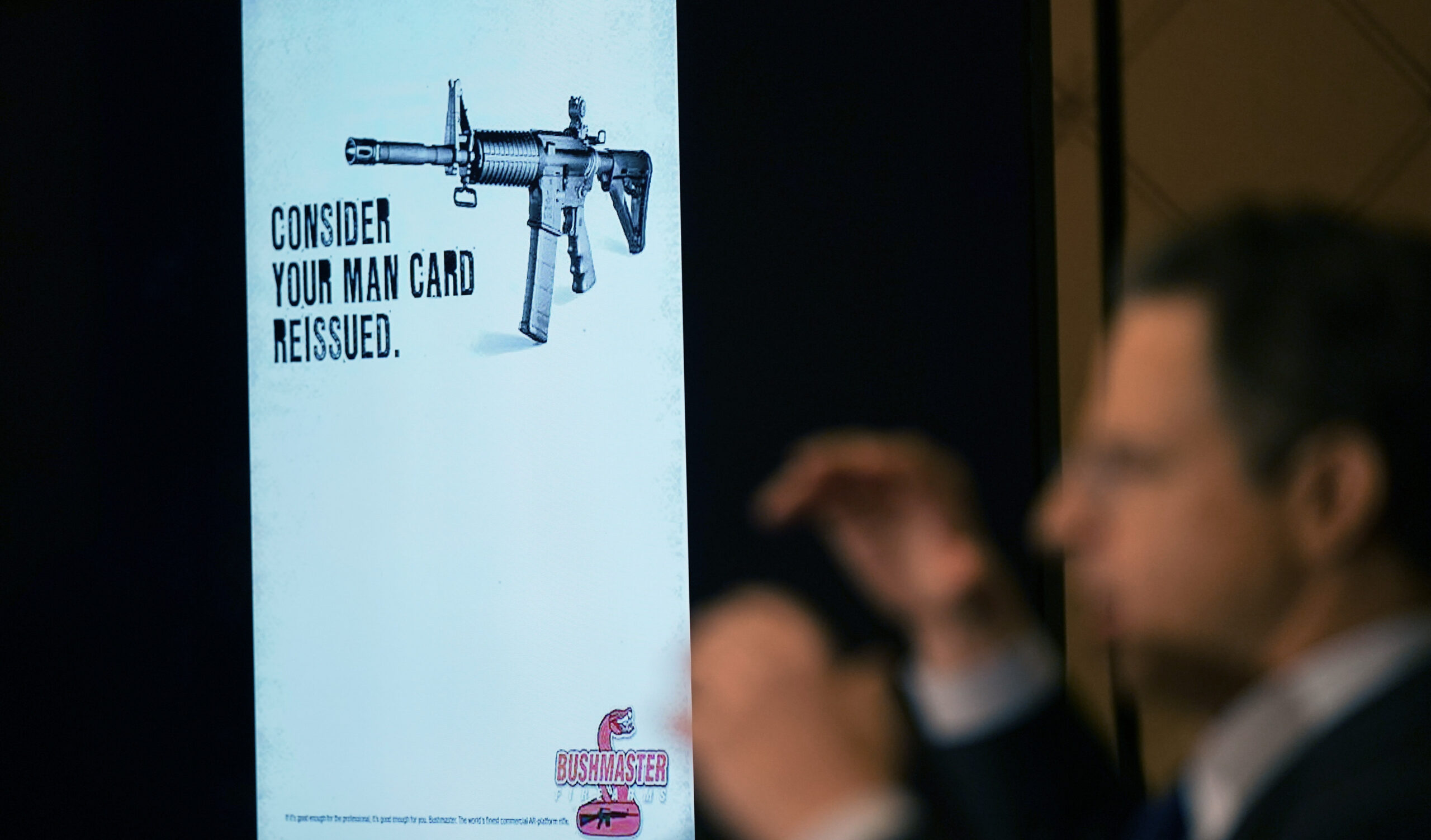

These questions were at the center of a recent lawsuit brought by the families of the victims of the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre against the gunmaker Remington Arms. The plaintiffs argued that Remington had violated a state marketing law by intentionally marketing its Bushmaster XM-15 rifle to young, unstable men. The families reached a $73 million settlement with Remington in February.

The new crop of state laws directly targets this exception by putting a law on the books that expressly regulates the sale and marketing of firearms. As a result, civilians and governments can sue for violations of the statutes and federal immunity won’t apply.

“There’s no debate that these laws qualify for [PLCAA’s] narrow exceptions,” said Jake Charles, a law professor at Pepperdine University who specializes in firearms law. “So there’s no longer any federal immunity barring these states from getting back in the business of trying to hold gun manufacturers and distributors accountable for policing their distribution chains.”

New York was the first state to pass a law requiring gun companies to impose “reasonable controls” on the sale and marketing of their guns. The bill, signed in July of last year, also revised the state’s statutes to define the illegal use of firearms and the unreasonable sale, manufacture, distribution, importing or marketing of those firearms as a public nuisance.

Delaware followed suit in June of 2022, New Jersey in early July, and California just a week later.

Minor differences distinguish the bills. In Delaware, for example, lawmakers struck down an additional state-level liability protection for firearm manufacturers. And in New Jersey, only the attorney general, not private citizens, can bring lawsuits against the gunmakers. But each of the laws serves the same purpose.

“The hope is not only that these laws provide an avenue for civil justice for victims and survivors of gun violence,” said Christian Heyne, the vice president of policy at Brady, the gun reform group which helped draft the bills’ language. “But that they provide incentives to encourage the gun industry on the whole to act more responsibly.”

Heyne said that if the laws stand up to scrutiny in the courts, they may ultimately cause gun companies to bifurcate their businesses: one distribution process for states with reasonable control laws, one for states without them. The change could mean a different standard for selling guns in some states, and could inadvertently create a nationwide case study into the efficacy of tighter controls on the distribution chain for firearms.

Pastor Michael McBride, the executive director of LIVE FREE, an anti-violence and racial justice organizing network, told The Trace that he and his peers have long puzzled over a way to hold corporations that manufacture guns accountable for their role in the 15,000-plus gun homicides in the country each year. He expressed uncertainty about whether these new laws incorporated input from people with lived experience of the racialized nature of gun violence — and whether their implementation would center the people most affected. But he said he was nonetheless cautiously optimistic about the strategy’s end goal.

“This economy of guns in our country creates a double loss in Black and brown communities — we’re both killed and penalized for killing,” he said. “To the extent that pain and accountability can be slingshotted back to gun manufacturers who profit off of this violence, this is an overdue reversal.”

So far, only New York’s law has been put to the test. Last December, the NSSF sued New York Attorney General Letitia James, arguing that the state’s public nuisance bill was overly vague and that it violated PLCAA. But in May, a federal district court disagreed, dismissing the suit. The judge presiding over the case wrote that “[n]o reasonable interpretation of ‘applicable to’ can exclude a statute which imposes liability exclusively on gun manufactures (sic) for the manner in which guns are manufactured, marketed, and sold.” In other words, the judge decided New York’s law fits PLCAA’s exception, unequivocally.

A month later, James used the new law to sue nine wholesalers, who she alleges shipped illegal ghost gun kits to New York residents for weapons that were later used in homicides. Her office did not respond to a request for comment.

New Jersey is also taking steps to use its new law. In July, Acting Attorney General Matthew Platkin inaugurated a new agency called the Statewide Affirmative Firearms Enforcement Office, which is specifically designed to handle lawsuits against gunmakers. “At a time when the U.S. Supreme Court is undermining states’ efforts to protect their residents from the carnage of gun violence,” Platkin said in the release, “New Jersey’s Statewide Affirmative Firearms Enforcement Office will use the new public nuisance legislation to hold the gun industry accountable.”

So far, no suits have been filed in Delaware, New Jersey, or California.

Andrew Willinger, the executive director of Duke University’s Center for Firearms Law, told The Trace that there will likely be challenges to each of these laws following the Supreme Court’s decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, which Platkin referred to in his release. The Bruen decision held that the Second Amendment confers a constitutional right to carry firearms outside of the home, relying in part on an argument that any new law regulating guns must have a historical analogue. Willinger said it’s unclear how courts will rule when asked to determine whether these new laws have sufficient precedent.