In the first week of September 2018, during Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings, the National Rifle Association’s board gathered for its final meeting of the year across the Potomac at the Westin Arlington Gateway hotel. The NRA was campaigning hard in support of Kavanaugh, whose confirmation would instantly shift power on the court in the group’s favor, and in anticipation, the trustees of an NRA legal fund approved $360,000 to back a slate of lawsuits, hoping to propel cases to the court.

Nearly four years later, the effort paid off. In an expansive June 23 ruling, the Supreme Court sided with the NRA in one of those cases, New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. As a result, millions more Americans will likely set about their daily lives armed with a gun and a range of firearm laws enacted by states, towns, and cities nationwide will be struck down because they do not match firearms restrictions of earlier eras closely enough.

At the same 2018 meeting in Arlington, the NRA legal fund also awarded a $12,000 grant to gun rights lawyer David T. Hardy, a supplement to the $15,000 that the fund had given him four months earlier to support his work on a book about mass killings, according to minutes that the NRA filed last year in a Texas bankruptcy court. Filings in that case and IRS disclosures show that the legal fund has awarded Hardy grants totaling more than $750,000 since 2002, though the full amount may be higher (the filings detail only a portion of recent grants). A former NRA official familiar with the arrangement, who was given anonymity in order to speak candidly, said that in addition to the grants, Hardy was long paid sums directly from the budget of NRA boss Wayne LaPierre, who was the best man at Hardy’s 1982 wedding. What appear to be internal budget documents released by a Russian cybercrime crew in October following its hack of the NRA list Hardy as a consultant and state that LaPierre’s office allocated $60,000 for him in 2021.

In July of 2021, Hardy submitted a brief to the Supreme Court arguing in support of the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc., which is a state affiliate of the NRA. (Though its affiliate’s name is on the case, the NRA funded Bruen, which was filed through the NRA’s Office of Litigation Counsel, according to NRA meeting minutes.) Hardy filed the amicus, or “friend-of-the-court,” brief as counsel of record to a PAC affiliated with the Firearms Policy Coalition and other assorted organizations opposed to additional gun restrictions.

He did not disclose the financial support he has long received from the NRA.

Reasonable people would question whether justices should be accepting these briefs. … The court needs to adopt a more exacting rubric centered on transparency.”

Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court

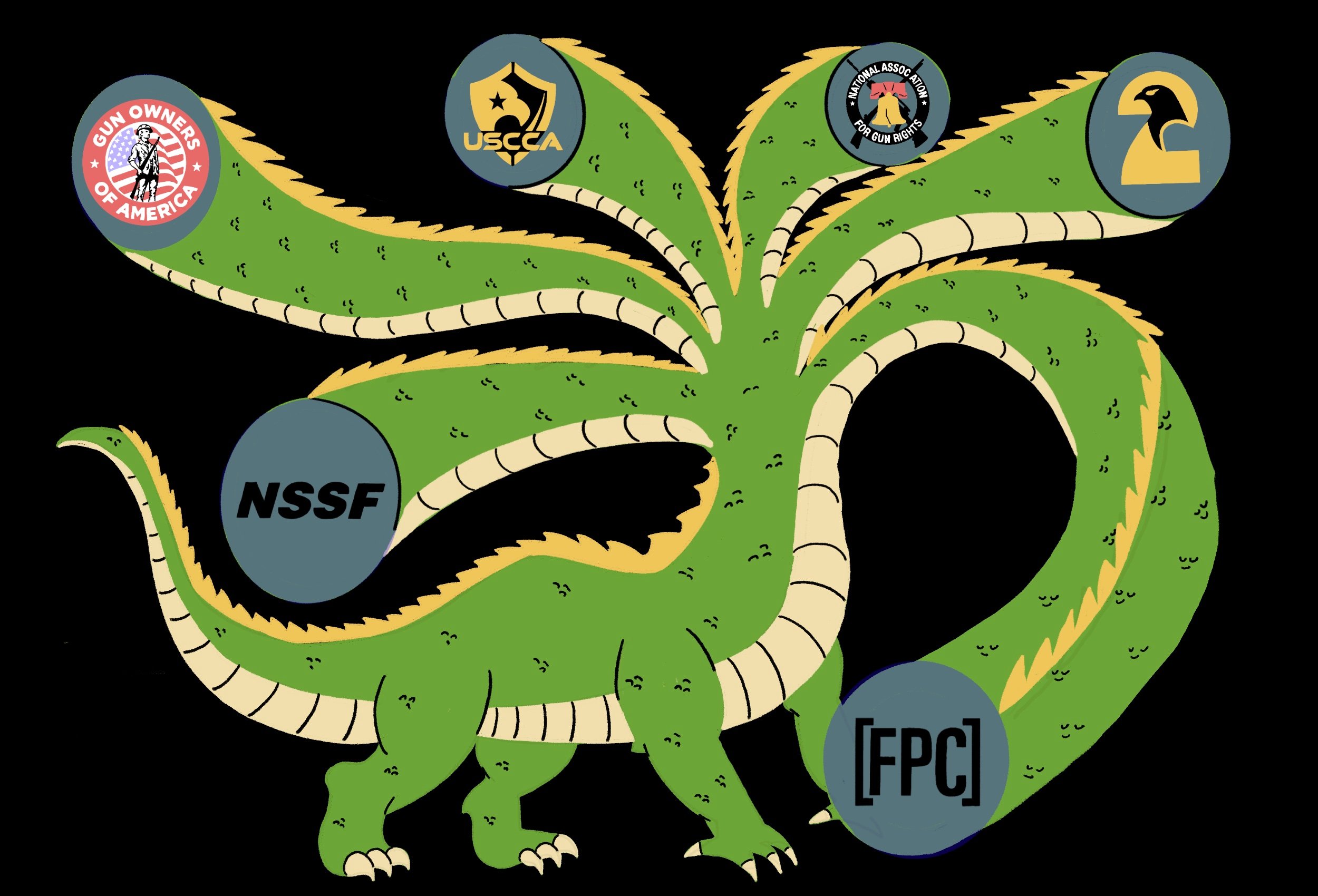

Hardy’s connection to the NRA is not unique. An examination of the 49 pro-NRA amicus briefs filed in Bruen, along with court and IRS filings, shows that, over the last two decades, the NRA has given financial support to at least 12 of the groups and individuals who lobbied the court on its behalf. That’s nearly a quarter. Though a full accounting is impossible, some recipients collected several million dollars from the NRA during that period and before filing briefs in Bruen. Only one of those 12 briefs disclosed the connection, meaning that neither the justices nor the public were told that 11 of these ostensibly independent voices owed their livelihoods in part to the NRA, the interest group behind the case. In his majority opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas adopted many of the arguments and conclusions offered in the amicus briefs filed by these NRA-funded allies, including Hardy’s.

The amicus briefs in Bruen provide a window into the NRA’s long-standing legal strategy — how the organization has spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the past few decades constructing an advocacy network of lawyers and institutions capable of identifying, supporting, and advancing cases likely to weaken gun restrictions.

But the briefs also demonstrate the limits of current Supreme Court ethics rules. The court’s guidelines surrounding financial disclosure for amicus filers are ambiguous and can be read so narrowly that experts say it’s easy for organizations to skirt them. Without a stronger rule, warn those pushing to bolster court ethics rules, groups like the NRA are essentially able to lobby the Supreme Court while keeping their role hidden.

“Reasonable people would question whether justices should be accepting these briefs,” said Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court, a nonpartisan group supporting more robust ethics rules and greater accountability for the federal court system. “The court needs to adopt a more exacting rubric centered on transparency.”

The NRA did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. Neither Thomas nor the Supreme Court responded to questions put to the court’s press office.

The NRA’s amicus machine

Over the past two decades, as more money and political energy have been directed at major Supreme Court cases, the marshaling of favorable amicus briefs — in which law professors and other specialists offer advice to the court, nudging it one way or the other — has become an industry of its own, a form of shadow lobbying targeting an institution that, in theory, is not supposed to be lobbied. The number of briefs filed surged, and justices have cited them with ever greater regularity. In a noted 2016 law review article titled The Amicus Machine, two professors from William & Mary Law School detailed how elite Supreme Court advocates employ “wranglers” to identify parties willing to file briefs and “whisperers” to ensure that filings convey the right message — one that is likely to be embraced by the justices. The result is a “systematic, choreographed engine designed by people in the know,” the professors wrote.

In part, that choreography is aimed at “creating the appearance of a groundswell of support for a given decision,” said Lisa Graves, a former Justice Department official who heads the progressive watchdog group True North Research. The NRA seems to have fully embraced this idea. Not only did the NRA fund Bruen, a cadre of attorneys paid by the association who were at the 2018 Arlington meeting where money was allocated to the case served as counsel on briefs filed by other groups lobbying against firearms restrictions. Two of its state affiliates and its legal fund also filed briefs backing the association. One organization, called The Center for Human Liberty, was incorporated in Nevada two months before filing its pro-NRA brief. Another, called The League for Sportsmen, Law Enforcement and Defense, was incorporated in Virginia nearly two months after it filed its amicus brief in Bruen. “Those of us involved with the League have been involved in 2nd Amendment advocacy for decades,” attorney Christopher Day, counsel of record on the brief, said by email in response to a request for comment. “The League is not affiliated with the NRA, nor received any financial support from them.” The League is led by James Fotis, who for many years oversaw an NRA-backed effort to elect judges and state attorneys general who opposed firearms restrictions.

Several briefs were filed by NRA-funded legal scholars whose work has been built on that of other NRA-funded legal scholars — a practice that Patrick J. Charles, senior historian for the U.S. Air Force, described as “citation gymnastics.” Charles, the author of Armed in America: A History of Gun Rights from Colonial Militias to Concealed Carry, filed a brief in Bruen as an independent scholar that supported neither side and called for “care in navigating conflicting and competing historical claims.” In an interview, he said there is support for some of what the pro-NRA briefs argue, but in sum they are a distortion. “They take a few facts, hype them, and assert that they have what they do not have,” Charles said. “They do this again and again, it’s just ridiculous. It’s completely dishonest. The NRA understood this early on, that you just have to keep putting information out there, insisting that it’s true, and people come to believe it.”

The NRA was certainly aware of the value of having plentiful briefs. Tom King is an NRA board member and director of the New York affiliate that is the petitioner in Bruen. He is also president of the NRA Foundation, which has given grants to groups and individuals that filed NRA-friendly briefs in the case. Speaking to an interviewer in January about how Bruen made it to the court, King said, “We had a lot of amicus briefs and [the justices] took the case.”

The amicus engine has a brake — at least in theory. Supreme Court rules require amicus filers to disclose whether any other entity — and especially parties in a case or their attorneys — have made a “monetary contribution” to the “preparation or submission” of a brief. The 2007 rule, which requires disclosure when funds have been channeled to the amicus filer or its attorneys, was prompted by concerns that litigants were silently financing favorable briefs.

Those pushing for court transparency say that the intent of this rule is frequently violated, and as a result, many briefs, which can require considerable research and expertise, are largely bought and paid for by organizations whose connections to the work are never revealed. Under the current rule, a party that chooses to read the word “preparation” in a limited sense could secretly fund a brief’s development from conception to finished document, so long as the friend of the court who formally submits the brief covers the minimal costs of final production and filing.

The financial ties between the NRA and Bruen amicus filers are indisputable. But it’s unclear whether any of the NRA money specifically funded the amicus briefs themselves.

In an email, Hardy said that while he could not remember who wrote the check for his work on the Bruen brief, it was fully funded by a Firearms Policy Coalition affiliate. “No NRA funds,” Hardy said, “were involved in any way — for my time, for the printing and filing costs, or anything else.” Hardy also said that while he was unfamiliar with how the NRA structures its budgets, his records showed that his last payment from the association came in 2019. Documents detail a grant to Hardy of $8,250 in January 2020 and another $10,000 in January 2021 for “research and writing projects.” Asked about those payments, Hardy said they were to support work on legal articles. In an email, the coalition media office seconded Hardy, saying that the organization had never received NRA money and that its Bruen briefs “were funded exclusively by FPC and our co-amici.”

Robert Dowlut, a former NRA general counsel and a trustee of the NRA’s legal fund was also present at the Arlington meeting where money was steered to the nascent Bruen case. According to IRS disclosures, the NRA paid Dowlut $3.7 million in salary and benefits from 2002 to 2018, when a payment of $154,070 was reported. He is counsel of record on an amicus brief filed in Bruen by a Massachusetts group called Bay Colony Weapons Collectors, Inc. Dowlut’s NRA ties are not disclosed in the brief, which states that only Bay Colony Weapons Collectors, which has about 60 members, funded the filing.

Dowlut did not respond to requests for comment. Karen MacNutt, Bay Colony’s treasurer and a longtime attorney and gun rights activist in Massachusetts, said that Dowlut, with whom she’d worked previously, approached her seeking an organization in the state willing to have him as counsel on a brief, and she suggested Bay Colony. “Bob Dowlut donated the labor,” MacNutt said. “The only money that passed was some nominal sum so that we could say we retained him.” MacNutt said there was no need for Dowlut to disclose his NRA ties. “He’s just an old lawyer out there who has an interest in this case,” she said. “I don’t think the NRA was funding this in any way. And I don’t think Bob was getting any money to do this.”

The NRA understood this early on, that you just have to keep putting information out there, insisting that it’s true, and people come to believe it.”

Patrick J. Charles, senior historian for the U.S. Air Force

Stephen Halbrook, a longtime outside counsel to the NRA, was also present at the 2018 legal fund meeting and also filed a brief in Bruen — for the National African American Gun Association. Halbrook is a senior fellow at the Independent Institute, a California-based think tank that has gotten modest NRA grants, most recently in 2018. He has also received direct NRA payments for decades. When the NRA filed for bankruptcy in January last year — a month after petitioning the court to hear Bruen — Halbrook was owed $26,550 under a legal services contract with the association, court records state. Halbrook’s pro-NRA brief in Bruen makes no mention of his financial ties to the group. In recent years, Halbrook has filed at least three briefs as counsel for the National African American Gun Association in other federal cases that do disclose that they were prepared and submitted with NRA funding. Neither Halbrook, whose work the NRA legal fund voted to recognize in January 2021 with a plaque and a $10,000 award, nor the NAAGA attorney on the brief, responded to requests for comment.

In November, The Trace reported that one of the hacked documents stated that the NRA had paid attorney David Kopel $267,000 a year in salary, benefits, and expenses for, among other things, Supreme Court briefs. In Bruen, Kopel is counsel of record on a brief filed by the Independence Institute, a libertarian think tank based in Colorado — not to be confused with Halbrook’s Independent Institute — to which the NRA has given more than $500,000 since 2018. Kopel’s brief makes no mention of NRA ties to him personally or to the Independent Institute. In response to a request for comment on this story, Kopel said that he wrote his Bruen brief in the late spring and early summer of 2021, during a 13-month period when his NRA grant had lapsed. He said that his calendar suggests he was at the 2018 NRA meeting where money was allocated to Bruen, but that he paid the case no attention until the Supreme Court took it up.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

California gun rights attorney Chuck Michel and his firm filed two pro-NRA briefs in Bruen on behalf of an array of groups. In April 2021, Michel filed a claim in the NRA’s bankruptcy case — a failed effort by the group to gain leverage in its battle with the New York State attorney general — stating that since July 2019, his firm had charged the NRA $843,000, including for work on “amicus matters” and was owed $289,000. Neither of his two briefs discloses a connection to the NRA or mentions any of the money his firm received. In fact, none of the five amicus briefs that Michel filed with the Supreme Court over the last three years in NRA-backed cases, all of which are posted on his law firm’s website, make that disclosure.

In an email, Michel said that “all sources of funding” for amicus briefs that his firm files in federal appellate courts conform to disclosure rules. Sent a copy of the Supreme Court rule and asked whether the same applied there, Michel responded with a press release for a gun rights lawsuit he planned to file against the state of California.

Graves, the former DOJ official, said a failure to reveal such connections is a blow to the court’s integrity. “It’s disturbing to see these ties and clear that the court’s disclosure rule is totally inadequate to reveal to the American public who the true funders are of these briefs,” she said.

The lone instance among the 12 briefs in which a link to the NRA was disclosed involves the association’s assistant general counsel, Sarah Gervase. She was counsel on a brief filed by a group called Italo-American Jurists and Attorneys. In that brief, Gervase identifies herself as an NRA employee and states that only Italo-American Jurists and Attorneys or its counsel made financial contributions to the preparation and submission of the brief, which she authored.

A less robust operation

While the questionable amicus advocacy of far-right political actors has drawn more attention, the disclosure rule is susceptible to evasion by liberal groups, as well. In Bruen, however, there is little evidence of a liberal effort akin to the legal influence network on the pro-NRA side.

“The rules as construed now certainly don’t favor one ideology or party,” said Roth, of Fix the Court. “But the conservative movement has more robust mechanisms for gaming them.”

No groups that advocate for gun restrictions were a party in Bruen, but they were deeply invested in the NRA’s defeat. Of the three largest such groups — Brady United, Giffords and Everytown for Gun Safety — only Everytown has identifiable financial connections to other entities that filed amicus briefs opposing the NRA. Legal directors for Brady and Giffords said they have never funded outside amicus projects. “Giffords does occasionally give contributions to other gun-violence-prevention groups to support their work,” said chief counsel and policy director Adam Skaggs, “but none of those contributions are conditioned on filing any amicus briefs in any litigation, and to my knowledge none of them have.”

In the case of Everytown, a review of IRS disclosures shows that since 2018, the organization has given grants to at least five of the 35 organizations that filed briefs backing New York State in Bruen. Those payments involved gun violence prevention grants as low as $5,000 to local chapters of the national organizations behind the briefs and are described in IRS disclosures as having a discrete purpose unrelated to legal advocacy, such as $25,000 given to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence in 2020 to sponsor a conference. (Everytown also provides grants to The Trace; see more about our funding here.)

By far the largest Everytown payment was a 2019 grant of $3.8 million awarded to March for Our Lives to promote “activism, civic engagement, and gun violence prevention,” according to an IRS filing. The group’s amicus brief in Bruen featured testimonials from young people affected by gun violence, rather than historical and legal arguments like those offered in the briefs that the NRA-funded allies submitted. “We did not get paid a penny for the work we did,” Ira Feinberg, a specialist in white collar defense who was counsel of record on the March for Our Lives brief, said by email. “We also had no contact with any other organization in the preparation of our brief, and dealt only with the staff of March For Our Lives.”

A coordinated network

Beyond the discernable financial ties between the NRA and amicus filers are a broader array of relationships that illustrate the general interdependence within conservative advocacy.

The counsel for the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. in Bruen was Paul Clement, U.S. solicitor general under George W. Bush. Affable in the courtroom, exceptionally lucid in his arguments and nimble under questioning, Clement has appeared before the Supreme Court more than 100 times and was among the elite Supreme Court advocates that the authors of The Amicus Machine interviewed. Clement sits on the board of The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, a conservative organization whose support for groups stoking former President Donald Trump’s bogus election fraud claims was detailed last year in The New Yorker. In 2020 and 2021, Bradley made grants totaling $2 million to groups that filed pro-NRA amicus briefs in Bruen. Grantees included the Independence Institute, Kopel’s Colorado think tank, which received $300,000 during those two years, and the Claremont Institute, which received $200,000 during the same period.

Almost all of Bradley’s grants to the Bruen amicus filers were for “general operations,” according to the foundation’s website. A Bradley spokesperson, Christine Czernejewski, declined to answer when asked whether Clement had abstained from approving the payouts, and said in an email that in such cases, “the grantee organization decides how to best use the funding, with no influence on the foundation’s part.” It’s impossible to draw a direct line from the money to the briefs. Moreover, the foundation had funded organizations that filed pro-NRA briefs before Clement joined Bradley’s board in 2020. Clement did not respond to requests for comment.

It’s disturbing to see these ties and clear that the court’s disclosure rule is totally inadequate to reveal to the American public who the true funders are of these briefs.”

Lisa Graves, True North Research

Paul Collins, a professor of legal studies and political science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, who has studied the role of amicus briefs, said that the current disclosure rule doesn’t contemplate the level of coordination that exists between filers and counsel for cases. “If Clement approved grants to organizations that filed briefs backing his own client in a Supreme Court case,” Collins said, “he’s probably in compliance with the letter of the rule, but not with its spirit.”

John Eastman, senior fellow at Claremont and a Trump legal adviser whose central role in the effort to overturn the 2020 election has been a focus of congressional hearings, is counsel of record on the Claremont brief, which the institute said was produced without outside support. In his brief, Eastman cites the work of Kopel and Halbrook. It’s one of at least 24 NRA-friendly briefs in Bruen that cite legal scholars whose work the gun group has long supported financially.

Revisiting the disclosure rule

For years, a small circle of watchdog groups and elected officials have claimed that the 2007 disclosure rule is too weak, but there have been few attempts to strengthen it.

The most high-profile effort has come from Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island, who has emerged as one of the most prominent critics of what he describes as the corrupting influence of dark money on the court. He has proposed a bill that would treat amicus filers more like lobbyists, subjecting them to registration and financial reporting.

Most likely, any near-term changes may come at the federal appellate level. The appellate court has a disclosure rule modeled on the Supreme Court’s, with nearly identical language. A federal court committee is examining ways to modify the appellate rule so that it better serves its purpose. Committee documents filed in the Federal Register last year note that the rule can be narrowly construed, making it “easy to evade” and state that, without adequate disclosure, litigants may “produce a brief that appears independent of the parties but is not. Another concern is that … one person or a small number of people with deep pockets can fund multiple amicus briefs and give the misleading impression of a broad consensus.”

It’s possible that that effort could lead to changes in the Supreme Court rule, as well. In September 2020, the clerk of the Supreme Court wrote to the committee that given the similarity to the appellate rule, the committee’s work “would provide helpful guidance” on whether changes to the Supreme Court’s own rule “would be appropriate.”

Daniel Epps, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis who has written about the court and worked for both Whitehouse and Clement, hopes to see the rule strengthened to provide greater transparency around the funding of amicus briefs. “What you want,” he said, “is a disclosure rule broad enough so that an organization won’t file a brief if what’s revealed is going to look bad.”