The street outside the Brownsville Community Justice Center used to be a hub for drug use and violence. The dead-end road lacked sufficient lighting, had hardly any overlooking windows, and little car traffic. The combination meant it wasn’t safe for the people who needed to use it as a pedestrian pathway. The surrounding neighborhood in east Brooklyn has historically suffered from some of the highest rates of gun violence and violent crime in the city.

Now, the street is a public plaza: tables and chairs, lush plants and trees, and a colorful mural reading “Brownsville Stronger Together.” It’s a well-lit, largely safe passageway between the Langston Hughes public housing towers and the bustling storefronts along Belmont Avenue. The broader 73rd Precinct, which includes Brownsville, has seen murders and shootings fall significantly since last year.

This remarkable transformation didn’t come about by accident. Mallory Thatch, a program manager at the Justice Center, has seen it firsthand: She helps oversee the center’s effort to improve Brownsville’s public spaces, including by organizing resources such as overdose prevention training and clean needle exchanges. The key, she says, is not going to extremes by cracking down too hard. “We don’t want to push these issues further into the neighborhood,” she said. “We want to remedy them at the source.”

As Brownsville, so Brooklyn. New York’s most populous borough has addressed the pandemic-era surge in gun violence with a strategy that would have once been a nonstarter: using police and incarceration as a last resort.

It appears to be working. Across New York City, shootings surged in the early months of the pandemic and continued throughout 2021. Brooklyn, however, saw violence fall in 2021, with a significant decline in both shootings and homicides. It has continued this year: Shootings are down roughly 20 percent, compared to the 11 percent decline in shootings citywide and 7 percent across the other boroughs.

But the new mayor, Eric Adams — the former Brooklyn borough president who ran on a “tough on crime” platform — has taken the opposite strategy to Brooklyn. He has called on prosecutors and judges to go harder on those who break the law. He has blamed the uptick in gun violence in the city on reforms to the state’s bail laws, and on prosecutors and judges for being lenient on lower-level offenses up to and including gun possession.

“No one takes criminal justice seriously anymore,” Adams told a news conference on June 6. “These bad guys no longer take them seriously. They believe our criminal justice system is a laughing stock of our entire country. We have to get serious about this, because innocent people are dying.”

In New York City, mayors are not in complete control of public safety, nor can they control the criminal justice system. Adams, however, has pushed for his counterparts in the courts and in prosecutors’ offices to adopt his rhetoric and his policy prescriptions.

By contrast, the Brooklyn district attorney, Eric Gonzalez, who was formally elected in 2017 (he took over the year before on an acting basis), has pledged to lead the “most progressive” prosecutor’s office in the country — and he hasn’t shifted his tone, even in the face of Adams’ calls for a tougher response to crime.

“My strategy has been consistent,” Gonzalez said in an interview. “I’m going to focus my prosecutorial resources on the so-called drivers. And I’m going to refrain from doing mass arrests, mass takedowns, or things that I think undermine our community’s trust in law enforcement.”

Instead of lots of petty arrests, Gonzalez has aimed to drive down crime without driving up prosecutions. He prioritizes early release in most parole proceedings, and his prosecutors are encouraged to resolve cases without jail time. He has also dismissed tens of thousands of low-level summonses.

Most notably, along with community partners like Brownsville Think Tank Matters, Gonzalez has developed intensive diversion and mentorship programs. These hand over responsibility in many misdemeanor cases to social services instead of jails. His office is also one of very few across the country that allows for diversion for people who carry guns but aren’t believed to be doing so maliciously.

“We saw people across America arm themselves for protection [during the pandemic]. And then we’re shocked that people in low-income neighborhoods are doing the same,” Gonzalez said.

“That program is something that I’m proud of. It takes a lot of courage to run it because, obviously, if any of those young people hurt someone with a gun in the future there’s going to be fallout.”

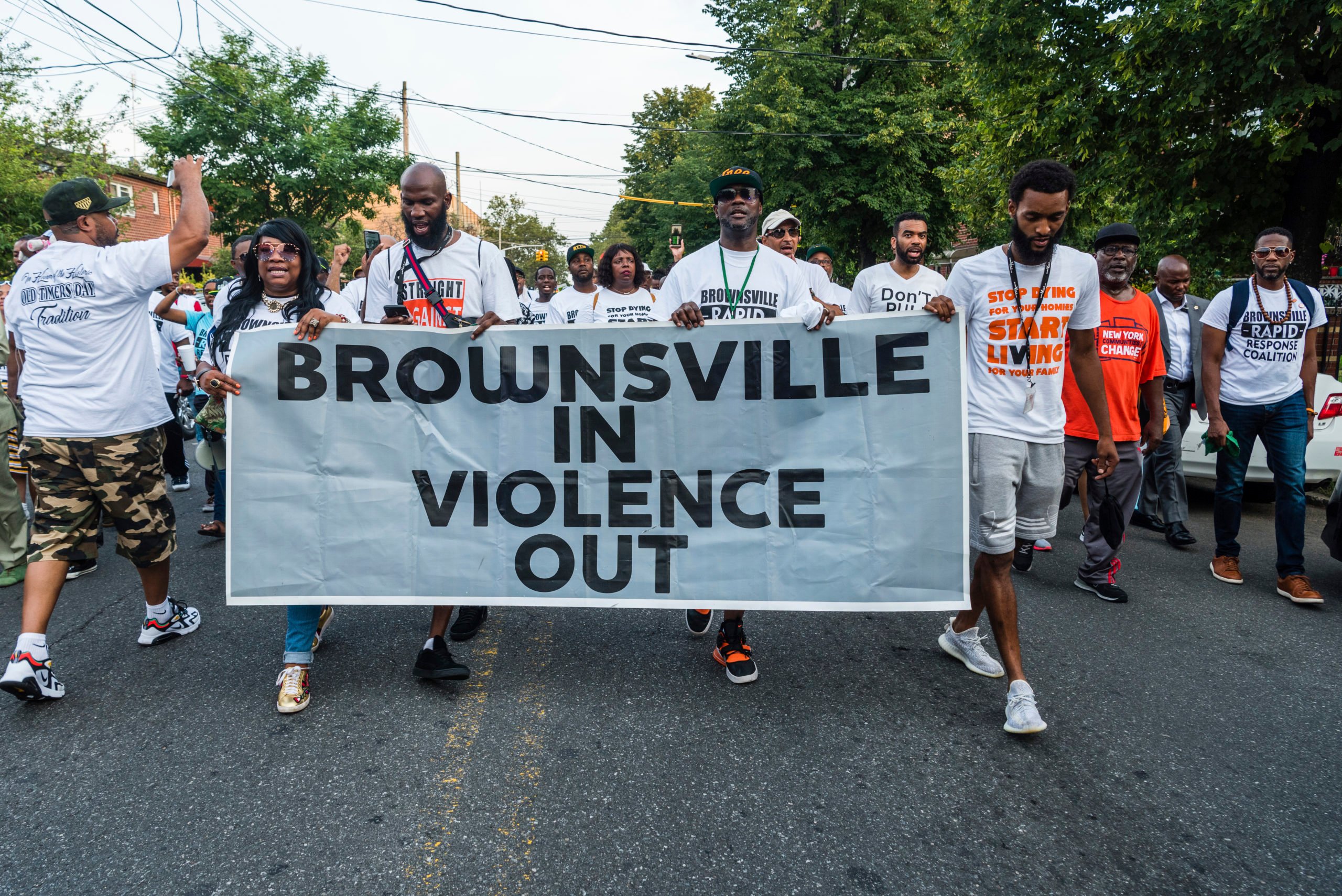

Gonzalez has also supported the Brownsville Safety Alliance, a community mobilization that pulls officers from several blocks for five-day periods, while a coalition of community groups gives residents help — with employment, food, job training, and mental health services. Violence interrupters are on standby to defuse any potentially dangerous situations.

These progressive policies may soon come into more direct conflict with those of the mayor. Adams has expressed support for community-based solutions to gun violence, but his first budget is set to cut funding for the city’s Crisis Management System from $135 million this fiscal year to $100 million in the fiscal year that begins in September.

Nevertheless, Gonzalez has maintained a diplomatic relationship both with the Police Department and with Adams, despite their differences in tone.

“His gun safety plan is a lot more than simply, ‘Let’s arrest more people and prosecute,’” Gonzalez said of Adams. “But I don’t think that that message gets adequately or fairly conveyed to the public. I hope that the things he’s saying will be reflected in our city budgets moving forward. That there’ll be more and more investments made in East New York and Brownsville, and other difficult parts of our city.”

While Gonzalez has focused on alternatives to police and incarceration, he has still worked with the NYPD on efforts to target and take down suspected gangs. He is concerned, however, about the intense rhetoric surrounding crime and public safety in New York.

“It’s hard to know exactly where the city goes on this, but I do know — as the district attorney of the largest county — that I’m always going to look at folks and use jail as a last resort,” Gonzalez said.

“The alternative is to get services in people’s lives to deal with the addiction issues, mental health issues, poverty issues that are driving a lot of this low-level offending.”

Though the causes of why shootings have declined in Brooklyn are complex, Gonzalez credits Brooklyn’s network of community-based organizations and its more-developed infrastructure of Crisis Management System groups. Those groups, too, say they’ve seen a lot of positive change.

“There’s been a lot of different types of investments in Brooklyn. There are a lot of more community-based efforts here, specifically with CMS,” said Hailey Nolasco, director of community-based violence prevention at the Center for Court Innovation, the parent organization of the Justice Center.

Though Gonzalez can’t control the Police Department, local police commanders have also been willing to shift their thinking on alternatives to policing, Gonzalez and the community organizers agree. They’ve been more willing to share information directly with anti-violence groups, intelligence that helps violence interrupters and outreach workers better target their services.

Brownsville still has problems. Numerous vacant storefronts still line the Belmont corridor; the landlords are hard to track down. There’s a lack of lighting on the sidewalks, which the Brownsville Community Justice Center has been imploring the city to address. The organization is also working with the Department of Transportation and design firms to clean up another dead-end road nearby that has also suffered from violence and drug use.

There is work to be done outside the physical space, too. Since 2020 the center has connected roughly 300 young people to mentors, paid internships, and entrepreneurship trainings. It also supports local Black-owned businesses, operates diversion initiatives, and provides legal help and housing resources.

Perhaps most important of all, these community-based efforts have transformed the notion that Brownsville is a home for violence, said Deron Johnston, the deputy director for community development at the Center for Court Innovation. Repairing those narratives of failure, which are often perpetuated by the media, is vital — and Brownsville now means something else than it once did, he said.

“This is a place where families are. This is a place where children are. This is a place where fun happens.”

An earlier version of this story misidentified the organization Deron Johnston works for. He is employed at the Center for Court Innovation.