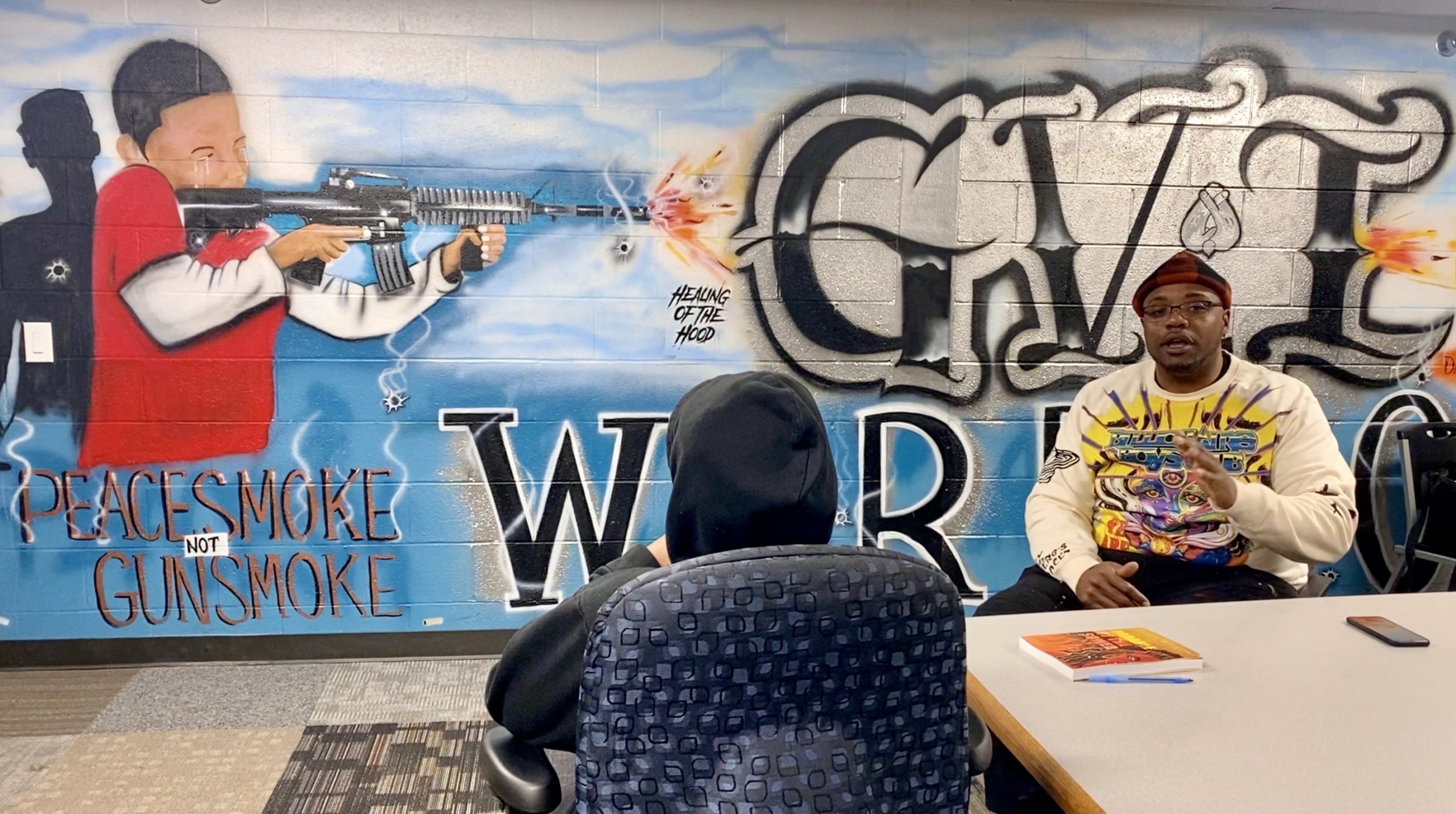

On a day in late March that still felt like winter in Kalamazoo, Michigan, an 11-year-old boy was sitting at the head of a conference table, staring at a graffiti depiction of a kid firing a gun. The boy had run into some trouble. He wore a hoodie and a face mask, leaving only his eyes exposed as Yafinceio “Big B” Harris spoke to him.

“I’m so happy you showed up,” Harris said. “That’s big, man.” The boy was quiet, barely audible in his answers to Harris’s questions.

The conference room they’re in was dubbed the “war room,” and it’s the heart of Peace During War, an anti-gun violence street outreach and support group. Since 2011, co-founders Michael Wilder, 49, and Harris, 46, have fought to persuade people — one at a time, in prison or at their organization’s headquarters, at family-style picnics and parties, to groups of school children — of the possibility of life without a gun, and without the likelihood of an early death or jail sentence. Peace During War helps people embrace their past and find hope in their futures, leveraging other organizations and resources to prevent further gun violence — a proven but slow salve in an increasingly uphill battle.

The young boy who Harris was trying to connect with had been temporarily removed from school for bringing in a bottle of liquor; afterward, a robbery landed him four felonies. Harris first met the boy a few days earlier, when the Group Violence Intervention (GVI) program, an ally of Peace During War, called him to the juvenile home to divert him from his path, with authenticity and empathy.

There, Harris invited him to meet again, which is how he found himself sitting with a small group of Peace During War and GVI members less than a week after his release. Harris turned to the boy’s mom, sitting on a couch in the corner: “I want him to know he has people he can talk to, he’s got somebody he can call on.”

“Yes, sir!” a colleague interjected from the end of the table.

Harris asked him why he brought liquor to school, who it was for. The boy didn’t say much until his mom asked him directly why he wasn’t answering the man, someone who was offering help. “You’re the one who asked me to bring you to see him here,” she said. Harris and his colleagues heard volumes in the young man’s silence, which left them wondering whether shame or fear held him back from sharing. Without saying a word, everyone left the room except Harris, a colleague, the boy, and his mother — leaving a smaller group where the boy would feel safer. They found out that the mother’s boyfriend was abusive but that, without the power to stop it or tools to process it, the boy turned to a makeshift support network of older kids.

That interaction demonstrated Peace During War’s approach: peers trying to get others from their communities to turn away from gun culture.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

“Both of us have extensive felony records. We have been to prison multiple times. We are career criminals according to the state of Michigan,” Wilder said in an interview sitting on the stoop of his house, where he was recovering from a quadruple-bypass heart surgery. “We’re using our negative past to help these young people’s future.”

In a city the size of Kalamazoo, with 76,000 residents, gun violence has hit record highs with numbers still small enough to feel personal: 13 people died by homicide in 2020 and 2021 respectively, up from four in 2018 and seven in 2019. Assaults with a firearm doubled from 211 in 2018 to 401 in 2021; there were already more than 92 through April this year. Public officials are ringing the alarm to quickly fix a problem decades in the making. Kalamazoo city and county governments have each pledged $1 million toward ending gun violence, and are currently putting spending plans together. Last month, the city allocated an additional $1 million of pandemic stimulus funds to youth programs aimed at keeping kids too busy and engaged to pick up a gun, including an estimated half million on a sports league.

Public safety officials know that they can’t solve the problem alone. In a written statement on the crucial value of partnerships, Chief Vernon Coakley said that “community members with moral authority over group members deliver a credible moral message against violence.”

This approach is neither new nor hypothetical for Harris and Wilder. But it costs time and money. They’ve taken on relevant jobs with other organizations to pay the bills associated with Peace During War. Small expenses, like taking kids out for meals or entertainment or new clothes, and dropping them off with a bag full of groceries to a home with a bare refrigerator, can add up. They also invest their time in being ready to answer a call and show up to keep someone from picking up a gun. They could do more, both Harris and Wilder say, if they had other tangible support, like money, from community leaders.

The Founders

In many ways, Peace During War is the reason Harris and Wilder, who first came to know each other as mortal enemies, are still alive.

Wilder was a street runner and drug dealer pledged against Harris in a cycle of retaliation for a murder: Wilder is blamed for one of his friends killing Harris’s cousin.

“I am not gonna stop until Michael is dead,” Harris says he told himself at the time.

After a stint at Jackson State Prison, Harris ran into Wilder at Kalamazoo Valley Community College, where they were both students. It was more than a year since they had seen each other. Separately, they’d each made a choice during their last incarceration to give themselves a chance, but on campus Wilder didn’t recognize Harris and Harris wasn’t sure if Wilder’s inspirational talk in class — or his new Gospel-focused life — was an act.

Misjudging an enemy can be a fatal mistake. So Harris kept up a front for a month, until he realized Wilder was sincere. “The past was in the past,” Harris said. “What happened had to be set aside to move forward.”

Harris eventually persuaded Wilder to join him at a longstanding pool establishment, where they started dreaming up Peace During War. (The venue was shut down following a deadly shooting shortly after.) The professor of their class put them in touch with a nationally syndicated show on NPR to tell their story. Then, in 2014, a local foundation and a professor at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo helped them make a minidocumentary. After many attempts to bring their story to teens, a local alternative high school invited them to an event. Peace During War was by far the most popular presentation, commanding the attention of the most difficult to reach kids at the school, and sparking Harris and Wilder’s public speaking careers.

The two men have since developed their own support network. To pay their own bills, they continue to work for other local organizations doing similar work. Wilder is employed as the local coordinator of GVI, the national framework for supplanting a traditional police-first approach to gun violence with one that recognizes the social context of a shooting. This can make for an awkward alliance between police and the street at times, though it allows Wilder, Harris, and their colleagues access to — and an exit ramp for — young people who are just entering the criminal justice system.

Harris works for Urban Alliance, a community organization that houses Peace During War, as a “connections coordinator,” leveraging his experience to ensure impact in a town where funding priorities are often top-down decisions. Harris and Wilder direct people to the Urban Alliance’s group counseling and job training programs. With its help, they are working toward designating Peace During War a formal 501c3 nonprofit so they can apply for grant funding and eventually earn a direct paycheck for their work.

The Work

The shape of a single day for Peace During War is determined by who comes or calls in for help. There’s a constant flow in and out of the “war room” and the newly painted offices in the basement of the Urban Alliance building, like a bee hive where everyone has their own purpose within the common mission. If the bees are not there seeking help, they volunteer or work for any of the other half dozen organizations with some sort of a presence in Urban Alliance.

Twenty minutes after the private meeting between the 11-year-old and Harris, Harris strode into the meeting room where everyone else had relocated, his phone on speaker. A friend who was locked up in federal prison was on the line, and told Harris that he had been up all night consoling his cellmate, whose brother had been in a car accident in Kalamazoo’s Northside neighborhood that morning. The man declined Big B’s offer to put some funds in his commissary, but thanked him for being there.

“I’m never too busy for you, man,” Harris told his friend.

He hung up and turned to a woman facing nearly a dozen federal charges, and who needed better legal help. She said she felt trapped: she can walk away if she snitches, the prosecutor told her. In her mind, that means she’s not a threat to society. So why, she wondered out loud, would she face a life sentence if she declined?

“I can’t—“ she starts to say, dark thoughts creeping in, trailing off just as those around her jumped in with support. “Don’t even go there,” Harris says, “remember what we talked about on your porch the other day.”

While a colleague processed receipts for reimbursement, Harris checked on the son of his barber who’s taking his GED practice exam in a nearby room.

Harris then stepped outside for a smoke break, holding the door open for a woman whom he introduced as having spent 15 years in prison and who now helped other young women avoid that route.

He pulled on his convenience store cigar and exhaled as he mulled over his experience alone in the room with the 11-year-old boy and his mom, the smoke disappearing in a wet spring snowfall.

The City and Its Disparities

Wealth inequality is particularly concentrated in Kalamazoo’s Northside, Eastside, and Edison neighborhoods, a stratification linked to racist housing and banking policies, according to the county mental health services provider Integrated Services of Kalamazoo (ISK). Those disparities have lasting impacts on residents’ health, well-being, and sense of overall safety.

So it’s not a coincidence that the vast majority of gun violence takes place in the city’s poorer neighborhoods, says Estevan “Esto” Juarez, a former gang member who is now a pastor and an ally of Peace During War. Last November, he was elected to the Kalamazoo City Commission.

There’s a causal — and harmfully logical —relationship between a lack of economic opportunities, generational poverty, and the choice of some to pick up a gun, he says.

“No one wakes up one day and says, ‘I’m going to pick up a gun and I’m going to be violent,’” Juarez said. “It’s a combination of different things that that individual had to go through to see for himself or herself that, well, at the end of the day, it really doesn’t matter because everything else has failed me.”

Recent national studies agree. In an August 2021 study published in The Lancet, researchers from Boston University and the University of Alabama at Birmingham traced the through lines — likely starting at redlining and segregation — which end with increased incidents of gun violence in poorer neighborhoods.

No one wakes up one day and says, ‘I’m going to pick up a gun and I’m going to be violent’”

Estevan Juarez, Pastor

“Racist housing policies have had direct consequences on the socioeconomic and demographic makeup of urban neighborhoods. These, in turn, have led to the disproportionate firearm victimization of, particularly, young Black men in these communities,” the study concluded.

Researchers from medical schools at Harvard and Northwestern University, the Albert Einstein School of Medicine, and children’s hospitals in New York, Chicago, and Boston found that people 24 and younger were at higher risk of exposure to gun violence if they were living in poor communities. The study was published last November in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Meanwhile, low-wage jobs, a lack of affordable housing, and inadequate economic development create a dangerous atmosphere where stress is compounded and leads to violence.

Peace During War tries to address all these issues. Instead of running armed crews, positioning young men as lookouts for police intent on busting the drug stash, they now get calls from police to mediate a street dispute.

“I get pushback from my community because they may see me with a police officer. Nobody likes to call the police,” Harris said. “My police buddy might get pushback from their police buddy saying, ‘Hey, why are you hanging with those criminals? They’re gonna bite you in the ass.'”

Now, the police and the community members are working together to help prevent gun violence before it starts.

Still, Harris said, it often feels like they aren’t getting the support they need from the criminal justice system and community leaders who wield the power. They don’t see enough action when they talk about reducing the negative pressure of the criminal justice system’s inflexibility and historic discrimination. “What are we gaining from stirring up all that hope? And then to get it crushed,” Harris said. “Then what? You know what we risk for that?”

The Results

In the nonprofit space, funding — and sustainability — often depend on measurable wins. There’s no way to calculate how many kids ultimately decided not to pick up a gun because of Peace During War, no “key performance indicators” to track how many kids decided to play basketball with other kids at the Urban Alliance instead of doing something else, instead of doing violence.

Instead of inventing new programs from the outside, Juarez says, city funds and efforts should provide opportunities and spaces for communitywide discussions to find solutions that will have impact.

But Wilder and Harris feel a sense of success when a kid opens up to them about food insecurity, and lets the duo spend $100 on groceries. And when students and parents come back to them, years later, to share how the group improved their lives, or when community members make sure someone recovering from heart surgery is never alone.

And then there are the bigger markers. One of the most basic but impactful indicators of the success of Peace During War and the community’s anti-gun violence initiatives is that, after two years of record gun deaths, no one has been killed so far in 2022, Wilder said during the interview on his front porch.

The next morning, police announced a 35-year-old had been found shot dead. “There is a war brewing as we speak,” Wilder said in a text message. “My team is getting ready to go talk to known shooters tomorrow to calm things down.”