Earlier this August, a traffic stop left a beloved police officer shot to death and another partially paralyzed, sending shockwaves throughout Chicago.

The following morning, Mayor Lori Lightfoot gave a speech pushing a narrative that’s dominated city news conferences and court hearings for decades. “We have a common enemy: It’s the guns and the gangs,” she said. “Eradicating both is complex, but we cannot let the size of the challenge deter us. We have to continue striking hard blows, every day. No gang member, no drug dealer, no gun dealer can ever have a moment of peace on any block, any neighborhood, not in our city.”

The mayor’s words frustrated residents and former gang members who say it oversimplifies the problem. “How could you say somebody needs to be eradicated? They need help. They need to heal inside,” says Sylvester Henderson, 36, who grew up on the city’s West Side. “If you really want to change the problem then you got to help the community grow, to build.”

Although Lightfoot spoke to the public with certainty, her own Police Department’s records can’t verify the narrative. The Trace analyzed incident data for nearly 34,000 shootings and found that in the past decade, detectives labeled fewer than three in 10 of them gang-related. Police categorized the cases this way even in instances when they didn’t have enough information to make an arrest. Data shows that police did not identify a cause or motive in the majority of incidents.

The Trace spoke with nearly 30 researchers, city officials, and community members about what, exactly, is known about the impact gangs have on Chicago. More than a dozen were current and former gang or clique-affiliated residents. These interviews, in addition to gang intelligence records and shooting data, reveal that assessing the scope of gang violence in Chicago is difficult, in part because of inconsistent police data and the changing nature of gangs, which have fractured. It’s not just a technical issue. People distrust the police after decades of misconduct, so they don’t talk to them all that much, leading to fewer shootings being solved.

“If in the course of the investigation of these shootings, CPD is looking in its own data for information about whether the people involved were gang affiliated,” says Deborah Witzburg, Chicago’s Inspector General for Public Safety, “it’s looking at the very same data that we identified as profoundly problematic and which the department acknowledged to be problematic.”

Witzburg, who previously worked as a Cook County prosecutor, believes that gangs do contribute to much of Chicago’s violence, but she says it’s a problem that the data can’t back it up.

CPD declined to be interviewed for this story, despite receiving a dozen requests. The Mayor’s Office did not comment on the findings, either, but said Lightfoot was referring to eradicating the root causes of gang violence, not gang members themselves.

Chicago isn’t the only city pointing fingers. Across the country, gangs have once again become a scapegoat for politicians and police navigating a violent crime resurgence during the pandemic. New York City is promoting gang takedowns as a cure, despite research showing their ineffectiveness. A county councilmember in Washington State called to reestablish a local gang unit. And city officials in Virginia are spending thousands on gang identification and intervention.

“Saying the word ‘gang’ makes the victim less sympathetic, it makes the situation less sympathetic, it creates an ‘other,’” says Andrew Papachristos, a professor and researcher at Northwestern University who’s spent years studying the city’s gang networks. “The reality is, gang members are also neighbors, brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, [and] employees.”

The narrative vs. the numbers

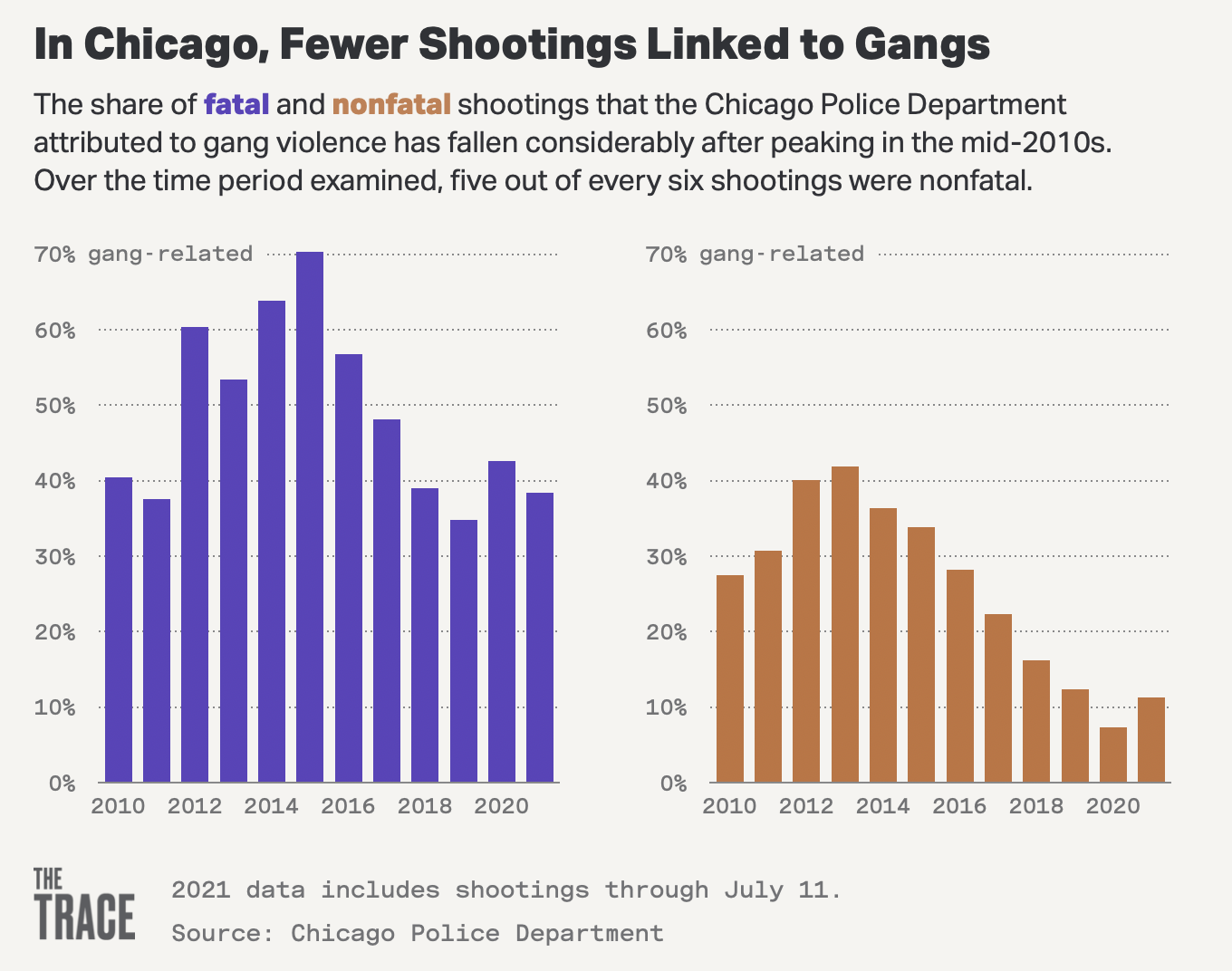

Since the mid-2010s, the Chicago Police Department has attributed a steadily decreasing share of shootings to gangs, The Trace found. Last year, CPD designated 43 percent of fatal shootings as gang-related, down from 70 percent five years earlier.

Over the same time period, the share of nonfatal shootings officially linked to gangs fell from 34 percent to 7 percent. It’s unclear what accounts for this decline. A few possibilities might explain it: Gang-related shootings are actually decreasing, detectives are unable to connect shootings to gangs because of their more fluid nature — or, simply, the information the police are able to gather is too limited.

Veteran researcher Roseanna Ander is the founding executive director of the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab, a research center that often analyzes Chicago police data. She isn’t surprised that CPD has only tied a small share of shootings to gangs. Ander says focusing on gangs distracts from the sheer number of guns available in the city.

“I think we would eradicate gun violence long before we could eradicate young people joining gangs, or cliques, or crews,” she said.

Still, it’s hard to say how reliable CPD’s numbers are. The shooting incident data The Trace analyzed was obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. It contains information on each shooting CPD responds to, and includes the date, time, location, and weapon involved in each incident. The Police Department also lists the motive and causal factors for shootings, which are often marked with descriptors like “narcotics,” “street gangs,” and “retaliation.”

CPD was more than twice as likely to label a shooting gang-related if the victim was Latinx, the analysis showed. Detectives were also more likely to attribute a shooting to gangs if it resulted in a homicide. These shootings were largely concentrated in predominantly low-income communities. Even in cases where detectives knew enough to make an arrest — less than 3,000 in the past decade — they labeled only a third as gang-related. The motive and cause for 75 percent of nonfatal shootings and a quarter of fatal ones is either left blank or marked as “undetermined.”

One police officer knowledgeable of CPD’s gang operations and homicide investigations believes the data undercounts the role gangs play in the city’s violence. “I do not think that the data accurately reflects the truth of what the situation is, by far,” said the officer, who asked not to be named out of concern for professional backlash. “If we don’t get that cooperation [from victims] we really can’t put that information in the system like that. Surviving victims, the level of cooperation we get [from them] is usually minimum to nothing. It’s very frustrating.”

The officer said the changing dynamics of gangs make it difficult to capture the underlying cause of a shooting. “It’s gotten so convoluted, how do you accurately report that? That decline is not surprising to me. This is gang related, it’s gangs — but it’s taken a different form.”

A 2019 review by a police association found that the department does not have comprehensive guidance for investigating homicides, which led to inconsistencies in the way they’re done. An Inspector General report that year also found that the department’s gang databases were inaccurate and out of date, and showed that CPD disproportionately targeted Black and Latinx residents.

It’s unclear how much of CPD’s nearly $2 billion dollar budget goes toward these types of anti-gang operations, which include publishing annual territory maps and audit reports on suspected gangs. The efforts come even though every level of government struggles to define what gangs actually are; sometimes, the same agency — like the Chicago Police Department — provides conflicting information about who they are and what they do. In general, the Chicago Police seem to define a gang as a group of two or more people with recognized leadership, who come together to commit crimes. CPD’s website claims that gangs have “become more violent,” despite its own data showing otherwise.

Chico Tillmon is a research fellow with the University of Chicago’s Crime and Education Labs. He says the Police Department’s data is reliable, but has limitations because of the department’s low clearance rate. “The challenge is with the qualitative data,” he said. “With a clearance rate at 20 percent, that means 80 percent of the data is missing. They don’t fully understand what’s happening.”

Tillmon, 50, grew up in the city’s Austin neighborhood on the West Side, and spent most of his youth in gangs. He says these groups reflect the poverty and desperation that communities face.

Chicago remains one of America’s most economically and racially segregated cities. Amid the skyscrapers on The Magnificent Mile, wealthy tourists and residents shop at pricey retailers where a pair of sandals can easily cost $200. Just four miles west, in the shadow of that storied skyline, some of the city’s young people live in poverty and surrounded by a pervasive sense of danger, where even a walk to school can feel perilous. These experiences can lead them to join cliques, which provide a sense of safety and community.

“Take a ride down Chicago Avenue. Start from Western, go all the way to Pulaski, and you’ll see why it’s so violent. It’s destitute, it’s broken,” Tillmon said of his neighborhood. “All those things are a perfect storm for violence.”

From gangs to cliques

Gangs have existed in Chicago for more than 100 years, transforming from predominantly white immigrant groups to Black and Latinx ones. The Trace analyzed annual reports published by CPD from 1965 to 2019, and found that the department rarely attributed murders to gangs or organized crime until the mid-’90s, the height of the “superpredator” era.

Over the past 30 years, most of Chicago’s historic gangs have deteriorated because of federal racketeering and drug prosecutions. The breakdown in leadership structures — and the city’s destruction of public housing projects — resulted in gangs splintering.

Many current and former gang and clique-affiliated residents reiterated a common refrain: They said gangs don’t exist anymore. Many of the small groups and cliques in their place don’t fit the definition that law enforcement bestowed on them: They often lack central leadership and not everyone who joins does so to commit crime. The reason for joining can be as simple as a desire to hang out with neighbors.

On a recent heat-stricken August day, a group of teenagers and young men shared their experiences with Chicago’s cliques — and their opinions on how connected the groups are to gun violence. The Trace is identifying the men by the initials of their last names only, out of concern for potential legal consequences.

Cliques are often named after their neighborhood, street, or a friend who was shot and killed, they said. Some members might focus on activities that aren’t based on a specific clique, like social media clout or making drill music, notable for its diss tracks against opposing groups, real or imagined. Some have lost their lives because of it.

If drugs are involved, it’s often individuals, and not cliques selling; and it’s mostly marijuana. Guns are more likely to be hand-me-downs than trafficked, one man said. Despite the changing landscape, the incentives for joining these groups have remained largely the same: safety and status.

“We don’t live differently than anybody else. We got dreams, goals, aspirations just like everybody else do,” said D. “The things that we do in our teenage years that are clique-related — it’s [a] phase you go through.”

Gangs, they said, have become a catch-all term. “They tend to blame everything on gangs and the music we listening to. I don’t really think it’s that,” said B., one of the young men. “I got homies that don’t gangbang. They in [a clique], but they go to college.”

Members said it’s rare for someone to act solely on behalf of their clique, or because its leader told them to do so. “There are no more gangs,” said D. “It’s Chicago, [the violence] is personal.”

They say conflicts, often called wars, can sometimes start over relationships with women — a reason that they don’t often discuss because they don’t want to be humiliated by friends.

Like people across the city, they’re horrified by the constant shootings and readily available supply of firearms. Though they feel the weight of the city’s violence is often pinned on them, most of the young men aren’t bothered by what officials say causes gun violence. They say they know the real reasons, and they’re just focused on surviving.

Two shootings on Wood Street

Kenneth Davis Jr.’s experience offers another perspective on a story that’s often one-sided. Before being released from prison earlier this year, he spent more than two decades reflecting on the incident that changed his life.

In 1995, Davis shot and killed a man in a small park on Wood Street in Englewood. Davis was just 18 at the time, and says he shot the man because he was chasing a friend with a machete. Although they were all in gangs at the time, Davis doesn’t consider his shooting to be gang-related. “This was not a matter of the Mickey Cobras and the Black P. Stones feuding — this had nothing to do with it,” he said. “It was me coming to the defense of my friend. … It wasn’t about the gangs. It was about the same sort of thing that these kids find themselves in today.”

Police didn’t buy it and neither did prosecutors, who won their case after they argued that the shooting was gang retaliation.

Davis says tales of gang-driven crime are so powerful because government and media amplify them. “It forces society to lose any sense of empathy for — in many cases — kids who simply have no interpersonal problem solving skills,” he said.

More than a decade after Davis fired the bullet that night in the park, another tragedy unfolded about a mile south on Wood Street, where Michelle Rashad grew up.

In 2011, a family friend named Corneilius Jordan, was shot and killed. “To this day it just angers me because I remember it was a case of mistaken identity, [the shooter] thought he was somebody else,” she said. “He died in the hands of our neighbor.”

Rashad, 29, directs Imagine Englewood If, an organization that provides youth development programs in the neighborhood. Her voice gets louder when she recalls reading the news article about Jordan’s death, which she says wrongly associated him with gangs.

“It was such a short article. It didn’t talk about him being a working man, it didn’t talk about his son, or how he would always put on a great fireworks show,” she said. “The story didn’t care about him being a human being. The story ended with him being gang-related, and that’s where it ends for a lot of people.”

A glamorous life

While officials have consistently blamed gangs, many people interviewed said they haven’t done much to change the reason a young person in Chicago might join one. They sometimes miss it entirely.

Just over a week after the two police officers were shot in early August, Mayor Lightfoot held an event celebrating her INVEST South/West initiative, a multimillion dollar plan to expand commercial and residential real estate in some neighborhoods. During the news conference afterward, Lightfoot attributed “dangerous gang members” to the city’s uptick in highway shootings.

“The biggest thing is, we’ve got to be united in our focus on rooting out this gang activity and going after the gangs — because that’s really what the heart of the problem is,” she said. “These are not random shootings.”

The Mayor’s Office said in its statement that Lightfoot believes the only way to improve safety is by partnering with residents, and that public safety is the city’s No. 1 priority.

Like many veterans who came up through Chicago’s historic gangs, Guillermo Gutierrez bristles at the sweeping statements people in power often make.

He grew up in the heart of Little Village, a predominantly Mexican neighborhood on Chicago’s Southwest Side. “My dad worked 50-60 hours a week. He was always tired, but unfortunately he was always broke, too,” Gutierrez said. “Right outside my door was that glamor life — these young guys hanging out had money, girls, and cars — so of course that was more attractive.”

He became so immersed in the lifestyle that he was surprised to realize he was still alive by the time he turned 21. He slowly began to redirect his time. Now 47, he leads the street outreach team for Enlace, focused on violence prevention and mediation. Gutierrez says violence is often caused by interpersonal disagreements or domestic violence. Recently, he said, it’s felt more and more random.

“Violence comes from frustration, from anger, from not having the rent, or not having food, or not having a good job,” he said. “Until we address those issues, I think sometimes it’s easier just to say it is a gang problem.”

Chip Brownlee contributed reporting and conducted interviews for this story. Daniel Nass contributed to the data analysis.