For decades, weapons manufacturing has been the domain of arms industry heavyweights: Glock, Sig Sauer, Remington, Sturm, Ruger & Co. Making a gun from scratch at home required thousands of dollars of machining equipment and years of engineering expertise.

But in recent years, that has begun to change. Advancements in 3D-printing technology have yielded increasingly reliable 3D-printed firearms, many of which require no federally regulated components to function. Below, we break down the basics of plastic, 3D-printed firearms, and the controversy generated by the swelling movement to deliver them to the masses.

What is a 3D-printed gun?

In the simplest terms, it’s any firearm that includes components manufactured with a 3D printer.

But 3D-printed guns vary a lot. Some models — like the 3D-printed gun company Defense Distributed’s “Liberator” — can be made almost entirely on a 3D printer. Others require many additional parts, which are often metal. For example, many 3D-printed gun blueprints focus on a weapon’s lower receiver, which is basically the chassis of a firearm. Under federal law, it’s the only gun part that requires a federal background check to purchase from a licensed dealer. To subvert regulators, some people print lower receivers at home and finish their guns using parts that can be purchased without a background check — metal barrels, for example, or factory buttstocks. Many gun retailers sell kits, which include all the components necessary to assemble a gun at home.

Advances in printing technology have driven the price of 3D printers down — they’re now around $200 on Amazon — and gun groups offer guides for getting started. These developments have lowered the barriers to entry for those in search of untraceable guns, which have turned up at crime scenes with increasing frequency over the past few years.

The process still remains more involved than most methods of obtaining a firearm, though. For instance, 3D printers require meticulous setup — the component that extrudes plastic must be calibrated, software must be downloaded to convert designs into 3D-printable slices, and the printer must undergo a slew of upgrades to reliably print weapons parts, which themselves require precise construction to ensure they can contain the explosion from a gunshot.

Why are they a big deal?

Because 3D-printed guns are made outside traditional supply chains, and don’t require background checks, they’re effectively invisible to law enforcement agencies. They are a form of ghost gun: unserialized, and unable to be traced if recovered by law enforcement.

There isn’t good data on the number of 3D-printed firearms that have turned up at crime scenes, though state attorneys general opposed to the technology insist that some have been recovered. On a few occasions, crimes involving the guns have made headlines. In February 2019, police arrested a Texas man after he was found test-firing a 3D-printed gun in the woods. He was prohibited from purchasing firearms and had a hit list of lawmakers on him.

Of particular concern to many law enforcement agencies are guns that can be completely 3D-printed at home without metal components. Politicians and law enforcement professionals fear that such guns would be able to evade metal detectors, and thus slip into places where firearms are prohibited, like airports or government buildings. At present, these fears are largely unfounded — 3D-printed gun designers have yet to develop an alternative to metal bullets, and security officials say that X-ray detection in place alongside most metal detectors can identify the outline of 3D-printed firearms with ease. Indeed, Transportation Security Administration officers have seized 3D-printed firearms at airports on several occasions.

Still, the weapons’ lack of traceability has already caught the attention of terror groups, according to Mary McCord, a former U.S. attorney and prosecutor in the Department of Justice’s National Security Division. “We know from a counterterrorism perspective that there’s great interest among terrorist organizations in being able to have workable, usable, efficient, functioning 3D-printed weapons.”

Is it legal to make a gun using a 3D printer?

In most cases, yes. Federal law permits the unlicensed manufacture of firearms, including those made using a 3D printer, as long as they include metal components.

In the absence of federal regulation, a handful of states have taken their own steps to clamp down on the creation of homemade guns. In California, anybody manufacturing a firearm is legally required to obtain a serial number for the gun from the state, regardless of how it’s made. In New Jersey, you are supposed to obtain a federal manufacturing license before 3D-printing a gun. The state also criminalizes the manufacture, sale, or possession of undetectable firearms, and made it illegal to purchase parts to make an unserialized gun. Several states — including New Mexico and Virginia — are considering bills that would enact similar restrictions.

What about sharing the blueprints online?

The legality of sharing the files required to print guns and gun components is murkier territory. No federal legislation bans the practice. But in 2013, the State Department ruled that releasing blueprints online violated arms export laws. In 2018, after a lengthy court battle with Defense Distributed over the guidance, the State Department settled, and agreed to permit the files’ release. But before the prohibition was lifted, a coalition of states sued to keep it in place — and won. Now, gun groups intent on sharing the files online have exploited a loophole in the State Department’s policy, which allows for the distribution of blueprints exclusively to U.S. residents. Defense Distributed maintains it has established a vetting procedure to ensure only U.S. residents are able to download them.

In 2019, the Trump administration transferred oversight of gun exports from the State Department to the Commerce Department, which would have rolled back restrictions on releasing 3D-printed gun blueprints. But a second suit filed by the coalition of state attorneys general has kept oversight of the files with the State Department, pending future litigation.

New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal is a plaintiff in the case. “If a company like Defense Distributed can simply sell printable [gun blueprints] to their customers without running the usual required background checks to make sure someone’s not a criminal, it would blow up the entire regime of firearm laws that we have in this country,” he said.

In 2019, after Grewal sought an injunction to block Defense Distributed from releasing files to New Jersey residents, the company countersued. It alleges that the blueprint files are a form of speech, and that Grewal’s effort to block their release violates the First Amendment. The case has yet to go to trial.

Who is printing guns — and why?

The first 3D-printed firearm to make a splash in the popular consciousness was the “Liberator” — a near fully plastic gun designed by a self-described anarchist and ghost-gun advocate named Cody Wilson. (Designs for the Liberator call for a small steel block to be sealed inside the plastic in order to comply with federal law.) Wilson founded Defense Distributed to advance and share the technology, and has initiated many of the group’s highest profile legal battles. In 2019, Wilson was sentenced to probation and ordered to register as a sex offender after soliciting sex from a minor.

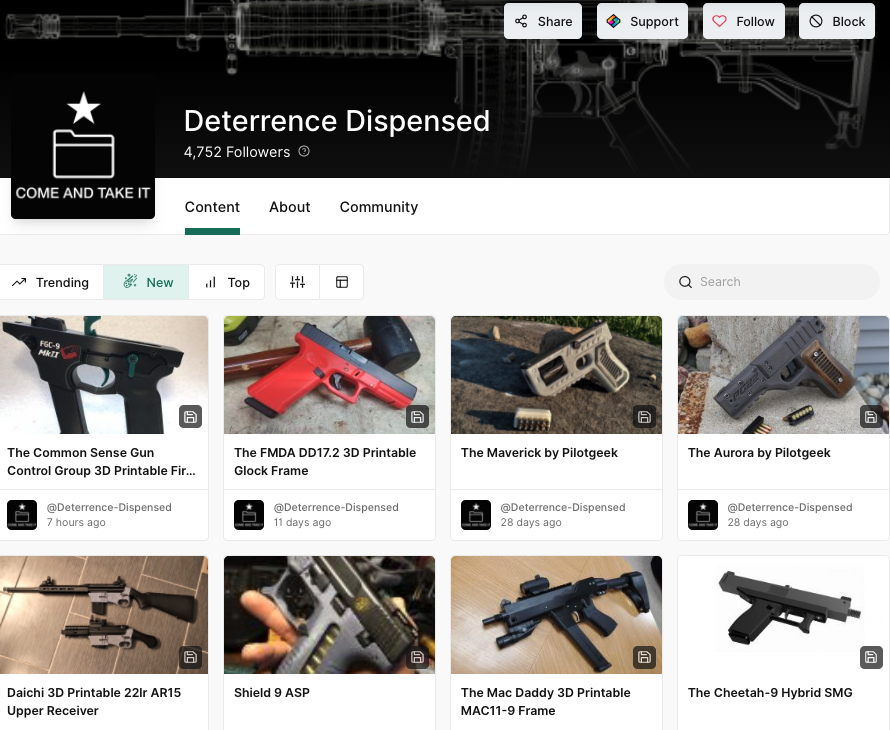

Though Wilson’s is the best-known and formally recognized gun printing “company,” the practice is mostly advanced by informal collectives across the internet. These groups, like Deterrence Dispensed and Fosscad, gather anonymously in chat rooms and on social media platforms to crowdsource the development of new gun designs and spread them across the web. They have thousands of members, but remain mostly decentralized, making it difficult for technology companies or law enforcement agencies to police them.

Over the past two years, however, the groups have run up against censorship policies at major tech platforms, many of which prohibit weapons content. As a result, they’ve been forced to increasingly obscure corners of the internet. Most recently, the operations hub for most of the 3D-printed gun groups — an encrypted chat and file-sharing platform called Keybase — pledged to remove all weapons-related content, and told the groups they would be banned.

Proponents of the technology fall into several different camps. Some, like Mustafa Kamil, a creator of 3D-printable guns based in Romania, and a member of the Deterrence Dispensed team on Keybase, think that concerns over homemade weapons are overblown. Gun printing, he says, is mostly the domain of hobbyists like himself: technical experts interested in tinkering and engineering. To 3D-print a gun: “you need to have enough money to buy a printer. Then you need enough expertise and experience to know how to use the printer. If your axis is off by 0.15 millimeters the gun isn’t going to work,” he said. “To buy a black market firearm would be much easier.” Kamil said he’s owned 32 printers and completed two apprenticeships with gun manufacturers.

Others see the potential for armed conflict with the government as the driving force behind their creations. Members of Deterrence Dispensed and Defense Distributed have fashioned a brand out of this perceived threat, adopting popular Second Amendment slogans like “Come and Take It,” “Live Free or Die,” and “Free Men Don’t Ask.” Leaders of the groups share a deep conviction that gun ownership is the only way to ensure freedom: In an interview with Popular Front, a conflict journalism outfit, the founder of Deterrence Dispensed — a man who goes by the username jstark — continuously pointed to the threat of government tyranny as a justification for creating 3D-printed guns and distributing their blueprints. “Just look at the Uighurs in China,” he said, referring to the ongoing genocide of the ethnic minority. “Just look what’s happening to them. No one’s helping them. Nobody does shit. You know what would help them? If they were armed. That would be a deterrence.”

To jstark, identical threats exist anywhere where civilians are largely unarmed, including in Europe, where he lives. When asked if he would fight police who tried to confiscate his guns, he was frank: “Basically, yes. Live free, or die. These are not empty words.”

Are these groups aligned with extremists?

While politicians and law enforcement agencies have dubbed the advocates of 3D-printed firearms extremists, the movement has no unifying political ideology. Jstark, for his part, said in the Popular Front interview that Deterrence Dispensed has no tolerance for people who wish to harm others: “If they do show through [their actions] that they’re extremists, racists, islamic terrorists — then we would kick them out immediately,” he said. He did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The alarmism about about looming government tyranny has attracted groups eager to ignite government conflict, particularly in the U.S. Members of groups connected to the boogaloo, a loose-knit coalition of anti-government extremists that advocates a violent civil war, have seen 3D-printed gun advocates as allies in an overlapping struggle. Last summer, Megan Squire, a professor at Elon University, tracked online boogaloo-connected groups as they navigated crackdowns from social media platforms. Many ended up on Keybase, drawn by the large and growing 3D-printed gun community.

In early April, Deterrence Dispensed released blueprints for a printable auto sear — a component that can be used to turn a semiautomatic rifle into an illegal, fully automatic firearm — called the “Yankee Boogle,” an apparent boogaloo reference. In September, two boogaloo adherents were charged for allegedly attempting to sell auto sears to representatives of Hamas, the Islamist extremist group. In court documents, prosecutors alleged that one of the defendants in that case said he obtained the auto sears from a supplier who 3D-printed them. In a separate case, federal prosecutors charged a man from West Virginia with 3D-printing auto sears and selling more than 600 of them online, including to several boogaloo adherents. One man who bought the 3D-printed auto sears is accused of killing a police officer and a security guard in California. It is unclear if any of the auto sears used in these crimes were designed by Deterrence Dispensed.

Correction: An earlier version of this article highlighted a case in which police in Rhode Island said a suspect used a 3D-printed gun in a murder. While police initially made that claim, an analysis by the state crime lab later ruled the method of manufacture “undetermined.” The story has also been updated to include that Defense Distributed’s “Liberator” gun model includes a small metal component for federal compliance.