In 13 states, a single judge is entrusted to decide whether the subject of a temporary order of protection is allowed to have firearms. The Trace wanted to understand how those decisions are made and whether they are aligned with evidence that the person who got the order is in danger of being harmed with a gun.

We looked at domestic protection orders in four states: Michigan, Arizona, New Hampshire, and South Dakota. We found that a person’s chances of getting a firearms restriction placed on their abuser are seldom tied to whether that person has threatened them with a gun. The decision is more likely to depend on which county they live in and which judge hears their case. Most states give judges wide leeway to make these decisions, offering little guidance about when gun restrictions should be granted or denied.

“So much is determined by judges’ biases,” said Tucson City Magistrate Wendy Million, who presides over the domestic violence court there. “When you have judges who think it’s a right to have a firearm, that’s a hard sell.”

The Trace found numerous examples of people who presented terrifying details and were still denied restrictions. A New Hampshire man who sent a woman a photo of a gun with bullets and said, “I want to commit homicide and suicide,” and, “I want people dead,” was allowed to keep his guns. In South Dakota, a woman who threatened to shoot her children’s grandmother in the head in front of them was also allowed to keep her gun. Conversely, we found some judges who granted gun restrictions to nearly everyone, even people who reported that their abusers didn’t have access to guns.

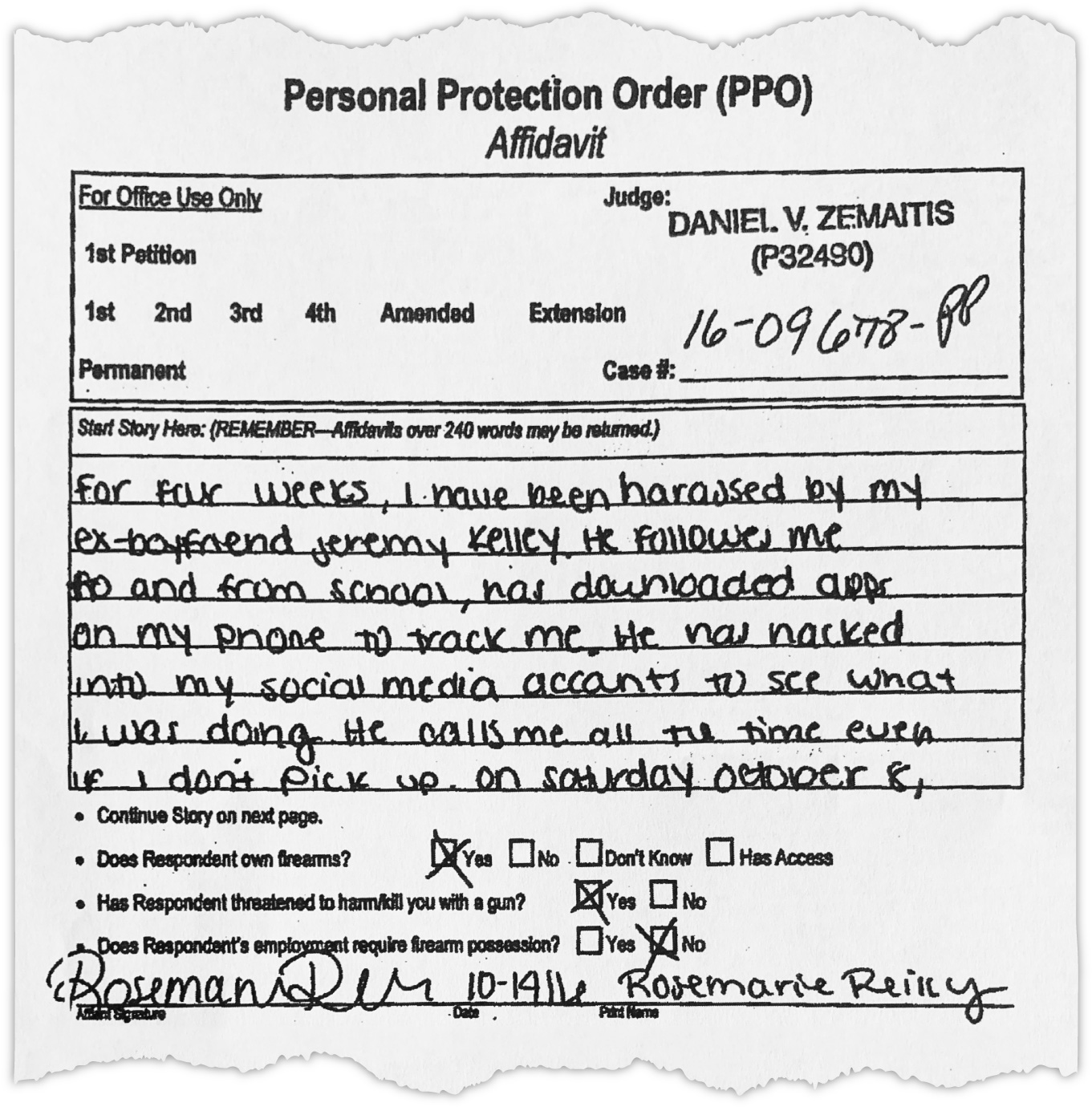

In Michigan, where Rosemarie Reilly lived, we found wide variation in the way firearms restrictions are handled from county to county. In rural Allegan County, just about everyone got a firearms restriction, whether or not they asked for one. Of 57 orders, 52 were granted with gun restrictions, including in 23 cases in which they weren’t requested. In Ingham County, home of the state capital of Lansing, there seemed to be little correlation between whether a person asked for a firearms restriction and whether they received one. About half the people who asked for a restriction got it. But about 1 in 4 people who didn’t request a firearms restriction got one anyway.

In Kent County, fewer than a third of the petitioners in October 2016 who said the subject of the order had threatened them with a gun were granted firearms restrictions on their order. By 2018, 94 percent of the people who asked for a restriction got one. Kent County court officials did not respond to questions about the change and whether it was connected to Reilly’s death.

The other states The Trace looked at seemed to grant gun restrictions on temporary protective orders arbitrarily. In South Dakota, about half of all petitioners were denied restrictions, even in a case in which a man threatened the petitioner with a gun and threatened to kill both her and her coworkers, and another in which a man had pointed a gun both at himself and at the petitioner and then shot into the air.

Krista Heeren-Graber, executive director at South Dakota Network Against Family Violence and Sexual Assault, said guidelines on when to remove a gun from the subject of a temporary protective order are fairly clear in her state, but filling out the paperwork is complicated. “It’s very concerning,” she said. “We know that when a victim is in the process of leaving [their] abuser, it’s the most dangerous time.”

In New Hampshire and Arizona, whether you get a gun restriction seems to depend on what courthouse you go to. In Tucson City Court, fewer than 50 percent of petitioners who asked for gun restrictions during the time period we checked got them. But petitioners who went to Pima County Superior Court, less than a mile away, had better odds — about 66 percent of them got gun restrictions.

In Manchester District Court in New Hampshire, 98 percent of petitioners received firearms restrictions. In Goffstown District Court, in the same state, none of the 10 petitioners were granted a firearms restriction, including a woman who said the defendant had promised to come over and shoot up her house.

Amanda Grady Sexton, a spokeswoman for the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence, said protective orders are only granted in truly serious cases in New Hampshire. Because there is already a high bar to get an order, she said it would make sense to include a gun restriction automatically. Petitioners need to prove that they have been the victim of a crime, that the abuse is current, and that they are in immediate danger of further abuse. “In light of all that, I’m not sure why a judge wouldn’t check that box to have firearms relinquished,” Grady Sexton said.

Grady Sexton said The Trace’s research makes it clear, above all, that data about firearms restrictions on temporary protective orders should be made publicly available.

“It’s problematic that we don’t have this data in a really transparent way,” she said. “Shouldn’t we know when there are huge inconsistencies from court to court and judge to judge?”

Additional reporting by Melanie Plenda, Claude Akins, and Jared Kaltwasser.