On March 22, Pennsylvania’s highest court dismissed a challenge to Governor Tom Wolf’s order closing gun stores as part of a broader curtailment of business activity meant to stunt the coronavirus’ spread. Wolf had presented the closure as crucial, so it came as something of a surprise when, two days later, the Democrat backtracked and allowed gun shops to reopen on a limited basis. Firearms retailers are now categorized alongside grocery stores, pharmacies, and other services deemed essential to sustaining human life.

Wolf has largely remained mum about his motives, but some observers saw the reversal as an attempt at sidestepping an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. “I think Governor Wolf recognized there was a chance the Supreme Court would rule against him,” Josh Blackman, a constitutional law professor at South Texas College in Houston who blogged about the case, said in an email. “He perhaps was unwilling to set a precedent that can weaken gun control laws.” Wolf’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

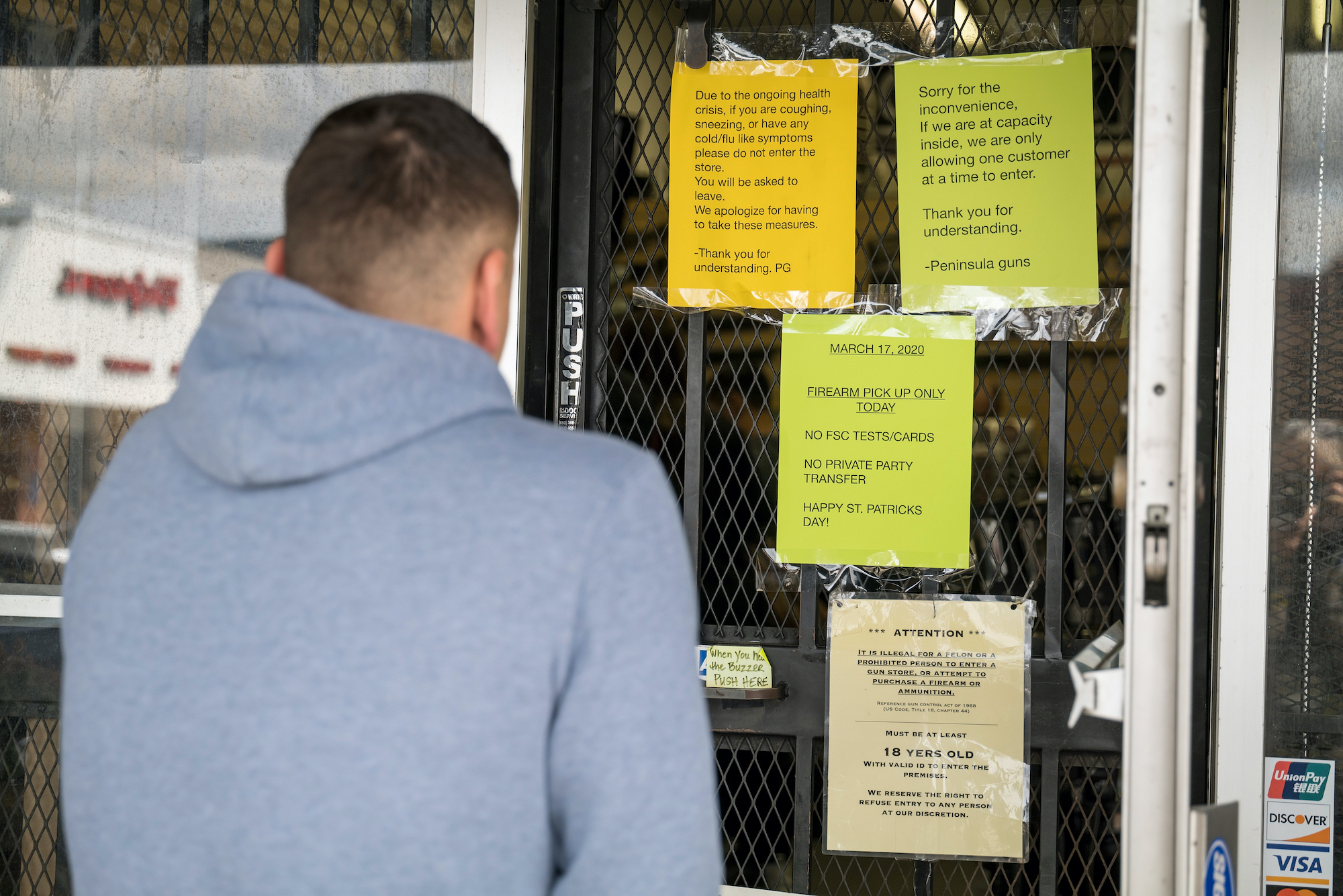

Stay-at-home orders have brought daily life in dozens of states to a virtual standstill, restricting people’s ability to assemble, exercise religion, and a number of other constitutional freedoms that Americans pride themselves on. But limits on gun rights have proven particularly contentious as states and cities force thousands of businesses to close but split on whether to extend the shutdowns to gun stores. The pandemic has spurred a record surge in gun buying. But some governors have waffled, deferred, or shied away from deciding whether retail firearm sales are too integral to jettison.

The controversy has pumped up the already charged atmosphere surrounding the Second Amendment, leading to new debates about the constitutionality of limiting gun rights during an unprecedented public health emergency. In addition to Pennsylvania, gun rights advocates have challenged state and local shutdown orders in California, Colorado, New Jersey, and New York. Additional cases could emerge as states tinker with their strategies in the face of the widening outbreak. But in recent days legal scholars have told The Trace that such lawsuits raise a mountain of thorny legal issues that courts have seldom debated — and there is little telling how they might rule.

“We’re in uncharted legal territory,” said Joseph Blocher, a Duke University law professor who has written extensively about the Second Amendment. “The questions coming up here are hard and novel,” he added. “There are some doctrinal guideposts, but not a whole lot of precedent that is directly on point.”

Gun rights groups have contended that closing gun stores is patently unconstitutional. The National Rifle Association accused “anti-gun lawmakers” of exploiting the pandemic to “eradicate” Second Amendment rights during a time when people are increasingly concerned about self-defense. But many experts say that constraining the ability of Americans to stock up on guns during a national crisis is a more complicated question than many public commentators have made it seem.

Still, the federal judiciary has shifted to the right in recent years, giving gun rights groups a leg up in their efforts to overturn the recent spate of gun store closures, and if one of their challenges makes it to the Supreme Court, conservative justices could swing a ruling further expanding the scope of Second Amendment protections.

The Supreme Court has not made a major Second Amendment ruling in 10 years, but with the addition of two Trump appointees, the court has signaled a greater appetite for such cases. Justices could use the gun store shutdowns to build on the landmark 2008 Heller decision recognizing the individual right to keep guns for self-defense, as well as the 2010 McDonald case, in which the court decided that Second Amendment protections limited the power of state and local governments. (Notably, however, the Heller ruling explicitly left room for laws regulating firearm sales.)

Courts weighing the lawfulness of recent gun store closures are bound to consider a host of factors, including the extent to which officials limited access to firearms and for how long. “The issue becomes how long is too long and how broad is too broad,” said Blocher, who recently penned a piece analyzing the relevant constitutional questions. “But I think it’s too easy to call the orders categorically unconstitutional because that depends on facts we don’t even know yet.”

What does seem clear, Blocher said, is that the closures do not amount to a ban on armed self-defense, since anybody with access to one of the hundreds of millions of guns circulating in the United States can still use it to protect themselves.

Gregory Magarian, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis, said judges would also examine whether the store closures were a byproduct of broader government efforts targeted principally at combating the coronavirus. This should be easy to argue, considering that the orders closed not only gun stores but myriad types of businesses. If gun stores were shut with the aim of limiting access to firearms to preserve law and order or prevent violence, governments might have a harder time making their case — though they could still have a compelling argument, given the depth of the health crisis.

Magarian said he had difficulty imagining the Supreme Court ruling that the Second Amendment precluded a state from including gun stores in a sweeping order closing businesses to fend off a pandemic. “But again, it’s still conjecture,” he cautioned. “I can’t think of another Second Amendment challenge to a regulation that restricts guns along with many other things as part of a broader regulatory scheme.”

Another question is whether gun sellers enjoy the same protections as gun owners. In 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco distinguished between the two, saying the Second Amendment did not “confer a freestanding right on commercial proprietors to sell firearms.”

To be clear, no one is arguing that gun store closures don’t encroach on the Second Amendment, but Adam Skaggs, chief counsel at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, said governments are generally given more latitude when a crisis calls for it. “The Second Amendment is not a super right that’s more important than the First Amendment or the right to travel,” both of which have been restricted under stay-at-home orders, Skaggs said. “In an emergency, the government is able to temporarily suspend activities that would be protected during ordinary times.”

Decisions to let gun sales continue uninterrupted during the coronavirus have cut across the political spectrum. Vermont’s Republican governor, Phil Scott, lumped gun stores in with other “miscellaneous store retailers” and required them to close. However, Democratic governors J.B. Pritzker of Illinois and Ned Lamont of Connecticut, both longstanding supporters of stronger gun control, let gun stores stay open as essential businesses.

Of the more than 30 states with shelter-at-home orders in place as of March 31, five required gun stores to close. A few states — including Pennsylvania and Delaware — have walked back orders and allowed gun stores to reopen with certain conditions. New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy, a Democrat whose administration had effectively banned all legal gun sales, including private transactions, reversed course after the Trump administration released updated critical infrastructure guidelines following lobbying by the National Shooting Sports Foundation, the gun industry’s leading trade group. The guidelines, which are meant to advise states about which operations to maintain throughout the pandemic, now include gun retailers and shooting ranges in the same section as law enforcement, 911 call centers, and emergency medical services.

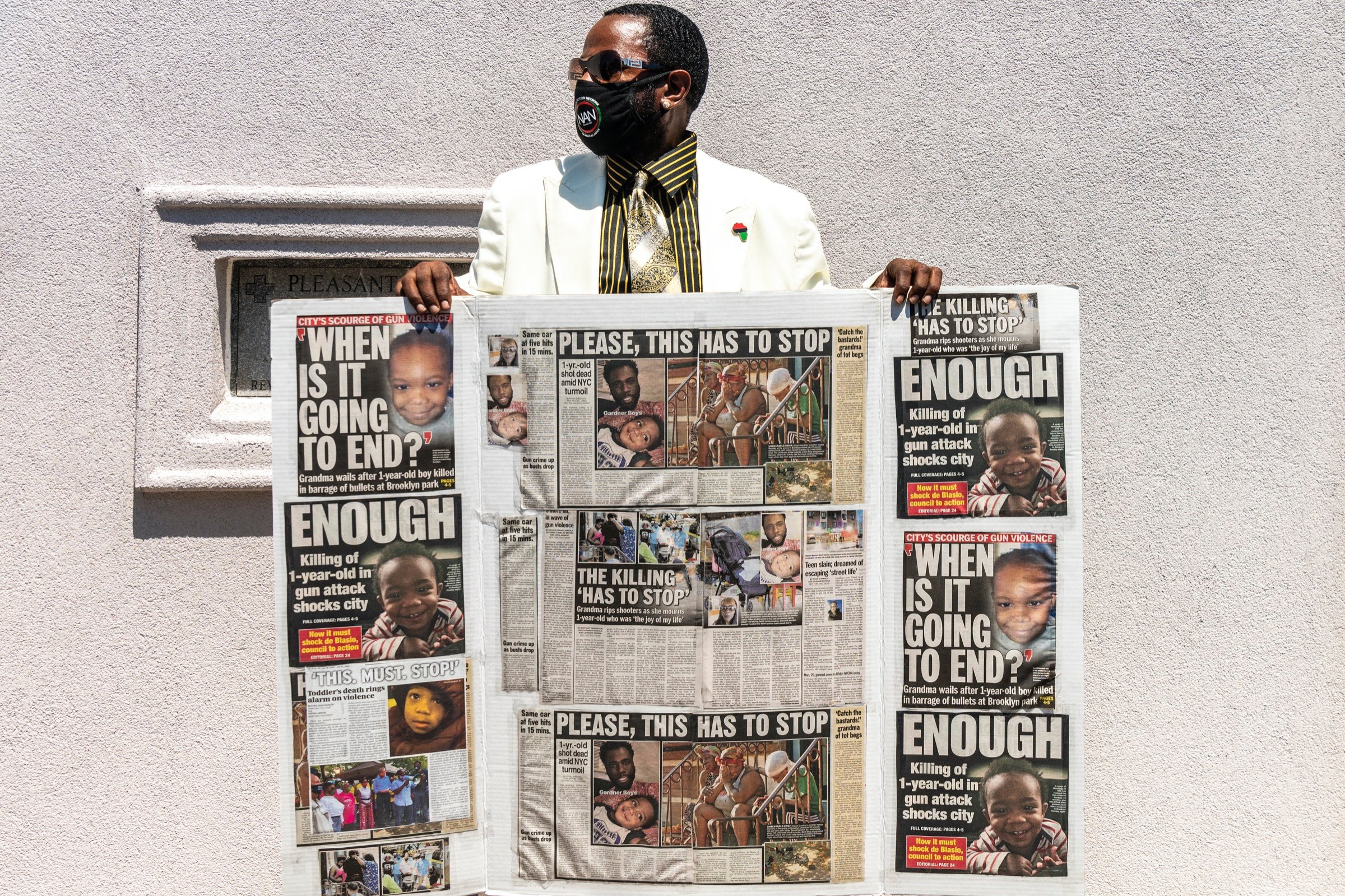

Gun safety advocates were quick to denounce the Trump administration, but they have also staked out some middle ground in the debate over what to do about gun stores during the pandemic. Shutting them down could drive buyers into the black market or unregulated private transactions. On the other hand, more guns in more places raises the risk of suicides and domestic violence shootings while large swaths of the country are under virus-inspired lockdowns.

“There are a lot of people bringing guns into their homes at a time when there is unprecedented economic pressure and social isolation,” Skaggs said. “It’s a recipe for disaster.”

In Pennsylvania, gun shop owners were pleased by Wolf’s reversal, but the back-and-forth amplified uncertainties during an already unpredictable time. At least some stores remained closed, either out of an abundance of caution or because they needed to restock inventory and figure out how to operate under the state’s new guidance.

Tracy Fornwalt, the owner of Morr Range in Lancaster, said her shop had cut its business hours in half and installed barriers between employees and customers. Now, she is just waiting for the crisis to subside.

“We wake up to something new every day it seems,” Fornwalt said. “It’s been a rollercoaster.”