The woman’s partner had never threatened her with a gun before.

But when she told him she had to go to work during the COVID-19 outbreak, he refused to let her, according to Katie Ray-Jones, CEO of the National Domestic Violence Hotline, to which the woman placed a call in mid-March. The woman told her partner that she had to go if she wanted to keep her job. Then he took out his gun and began to clean it.

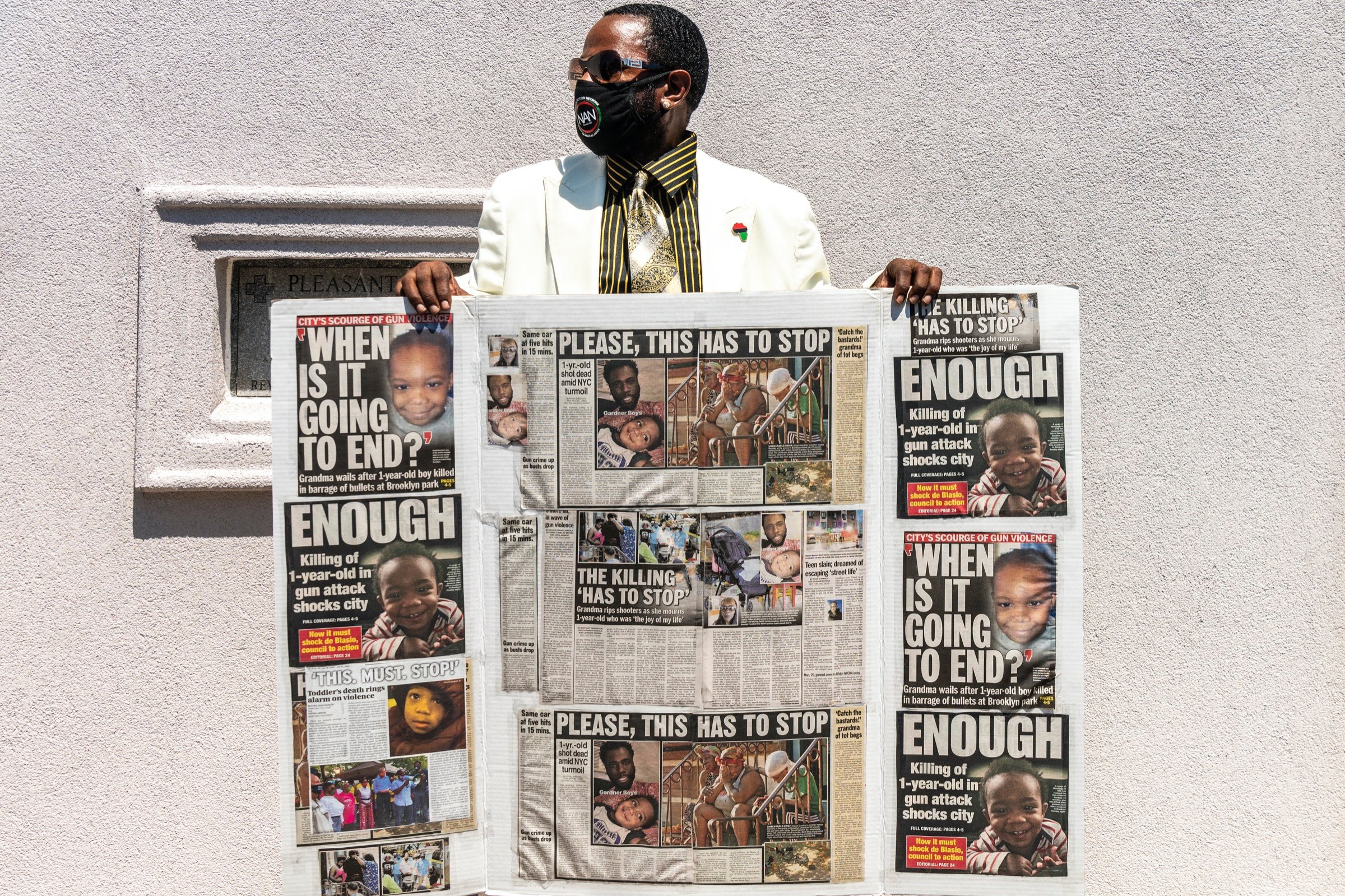

As people across the country are asked to curtail their social interactions, Ray-Jones and other advocates fear that abusers might become more violent and coercive. Financial anxieties, close quarters, and health concerns all bring extra stress into the home, and are associated with a higher risk of abuse. Add skyrocketing gun sales to the mix, and Ray-Jones says she has serious reason to worry about abuse victims’ safety.

“Abusive partners don’t cope well when they feel like they’re losing control,” Ray-Jones said. “And it often causes them to reassert their control over their partners.”

One concern, Ray-Jones said, is that survivors trapped at home with an abuser might be less able to reach out for help. Typically, domestic violence survivors seek help when they’re outside the home, at work or visiting with friends. Cooped up, they may no longer be able to call the hotline without fear of being discovered. Ray-Jones said the hotline saw a slight dip in the number of calls during the week of March 16, but that calls have since gone back to a more normal rate. She’s not sure whether the dip occurred because victims could not get away from their abusers to reach out, or because they were busy dealing with other crises and tasks, like a lost job or the need to stock up on food.

Calls to child abuse hotlines are also down, according to ProPublica, and experts say that is almost certainly due to abuse occurring out of sight, rather than an actual decline. Meanwhile, advocates in Cincinnati reported a 30 percent increase in hotline calls and some Arizona help lines have reported a 10 percent increase since social distancing began. Advocates had noted a similar phenomenon in China.

Many of the people who called the hotline in March reported that their abusers were making threats related to the pandemic. Some said their abusers threatened to kick them out of their homes amid the outbreak, even though they don’t have any place to go, Ray-Jones said. Others reported that their partners said they wouldn’t pay for medical care. Some callers said their abusers claimed to be infected with the virus, and threatened to infect them, too. One woman said her partner is controlling how many squares of toilet paper she is allowed to use per day.

David Keck, director of the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence and Firearms, said he’s been alarmed by reports of people buying guns because they fear the pandemic will lead to lawlessness. Research shows that an abuser with access to a gun is five times more likely to kill his victim than one without. Even when abusers do not shoot or kill their victims, Ray-Jones said, they often use the threat of gun violence to rape, terrorize, or to hold them hostage. Ray-Jones said reports that many people buying guns now are first-time gun owners with no training or experience are also troubling, since novice owners are more likely to store a gun unsafely or fire one accidentally. She said the hotline plans to track calls related to newly purchased guns, in order to better understand to what degree they are being used to threaten victims.

Keck also stressed that victims should suppress the urge to arm themselves, because there is no evidence that having a gun will protect them from a dangerous partner. “If you are a victim of domestic violence, don’t think arming yourself is going to make you safer,” he said. “It’s not, especially when anxiety levels in your home are high.”

Not all advocates agree that the pandemic is likely to exacerbate domestic violence. Ruth Glenn, president of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence said the fact that many abusers will be shut in with their victims may actually make them feel more secure, and less likely to lash out. “They may think, ‘I have proximity to you, you don’t have access to anybody else,’” Glenn said.

Her organization has been helping its members, which include shelters and advocacy organizations across the country, come up with plans to serve survivors through the pandemic. In shelters, that may mean creating more physical distance between residents while they eat and sleep, or sending home nonessential employees so they will be ready to report to work if others get sick. For abuse victims not living in shelters, it means finding safe ways for them to keep in touch with advocates using text, phone, or video conferencing.

Data released by the hotline on March 25 shows that roughly 6 percent of the 951 callers who mentioned the COVID-19 crisis between March 10 and March 25 also said that they had been threatened or harmed with a gun. Callers who mentioned COVID were more likely to mention guns than callers who did not. Still, there wasn’t an overall increase in the percentage of callers who mentioned guns compared to those who called in 2019. A spokeswoman for the organization said it’s too soon to draw any conclusions about these numbers, but said they are continuing to watch for trends.

Julie Bankroft, a spokeswoman for the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence, said her staff has been helping some survivors come up with safety plans that involve staying in the same home with their abuser for now. That might mean finding a door they can lock themselves behind in an emergency, or a way to lock away guns or remove them from the home before an incident occurs, she said.

One person who called the National Domestic Violence Hotline in the past few days said that their spouse had threatened them with a gun. The abuser, who is an alcoholic, has been going to work every day but will be home for the next month because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The caller was particularly worried about the safety of their five children. The hotline advocate helped the caller make a plan to get rid of the gun, and provided a list of local resources.

Beth Oswald, executive director of Christine Ann Domestic Abuse Services in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, runs a 37-bed shelter for women fleeing domestic violence. The shelter is remaining open, in spite of the health risks. “We are assuming that someone here, a staff member or a client, will have it,” she said of the coronavirus. She has a plan to isolate sick people within the shelter, giving them their own rooms and delivering food to their doors rather than having them share the kitchen as they typically do. Right now only 10 of her 30 employees are working inside the building; the rest are at home. If one worker gets sick, a healthy person in self-quarantine will come in to relieve them. That said, Oswald is concerned about basic supplies like face masks and cleaning products, and worries that an economic crisis will disrupt the shelter’s future funding.