On Wednesday afternoon, a disgruntled employee armed with two handguns stormed the Molson Coors Brewing Company in Milwaukee. The man, a 51-year-old electrician, killed five coworkers before killing himself.

The shooting triggered the usual spasms of national grief: The president offered condolences, Democratic legislators promised gun reforms, and reporters descended on the Miller Valley neighborhood on the city’s west side to chronicle the tragedy and its aftermath.

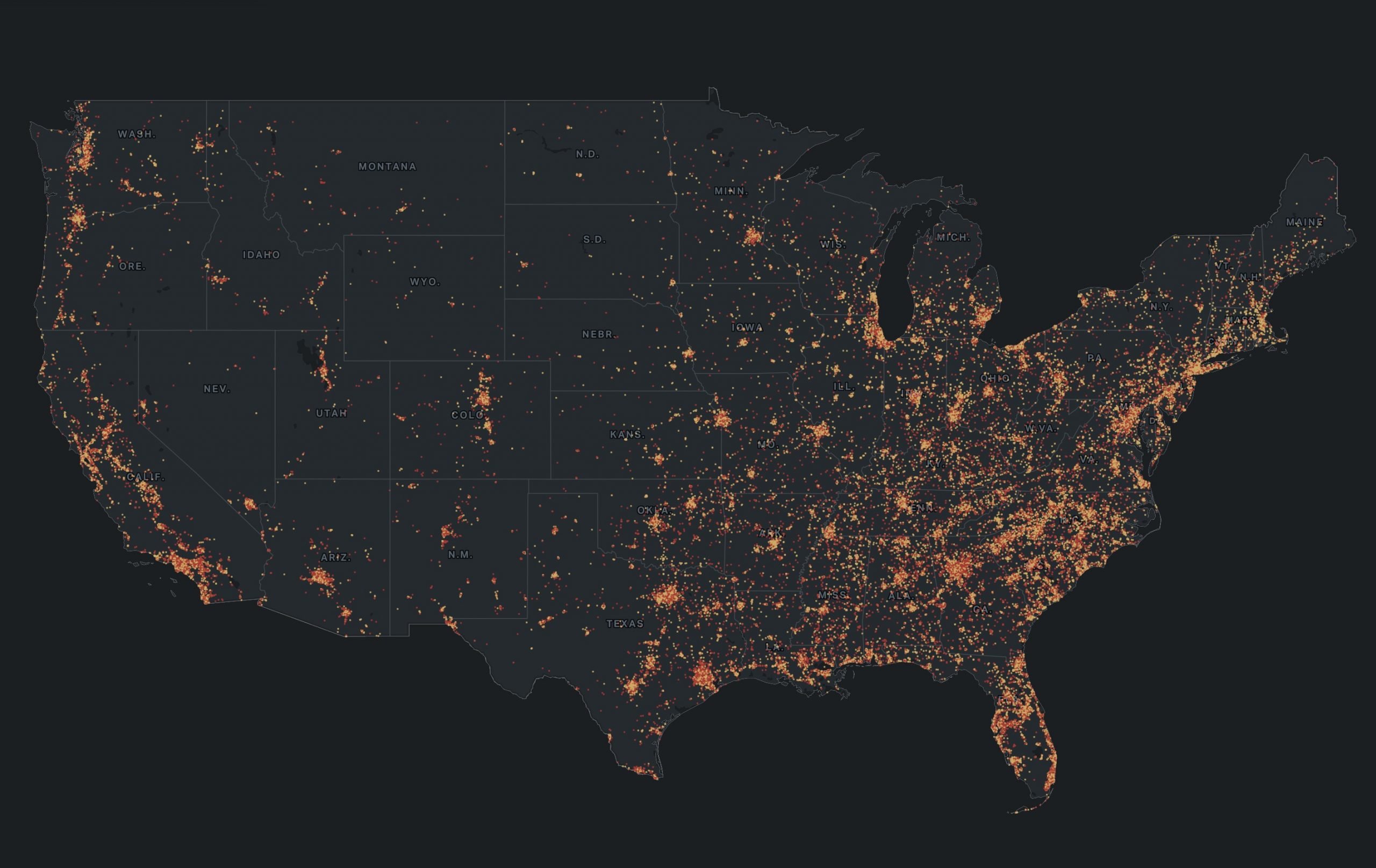

But for many local activists and organizers, the reactions, while wholly justified, glossed over the reality of gun violence in Milwaukee: a chronic problem that affects hundreds of lives each year. The city’s murder rate consistently ranks in the nation’s top 25, reaching a 20-year peak in 2015, when 145 people were killed. Within a one-mile radius of the Molson Coors campus alone, there have been at least 165 shootings since 2014.

“I don’t think [the attention from the Molson Coors shooting] is taking anything away from the issue of gun violence,” said Vaun Mayes, the founder of Community Task Force MKE, a grassroots organization of residents, advocates, and legislators trying to reduce violence in the city. “But I do think it’s diverting us from the actual issues and root causes.”

Those causes, he says, are starting to be addressed — but need more public investment. Indeed, in each of the last four years, homicides in the city have declined. According to Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, the success owes in part to an ambitious, collaborative approach to violence prevention that advocates like Mayes have worked to create. The city has dubbed it the Blueprint for Peace.

According to its 96-page guide, the Blueprint aims to put forward “a unifying vision and overarching plan” for violence prevention that will “address the underlying factors that contribute to violence, build on community assets and culture, and systematically apply data and science to ensure effective solutions.” In other words, it combines a variety of well-tested violence reduction strategies — among them focused deterrence, violence interruption, cognitive behavioral therapy, and hospital-based intervention — to tailor a response specific to Milwaukee’s cultural and political moment. The program is coordinated by the city’s Office of Violence Prevention, and involves community groups from all over Milwaukee.

The relative success of the program has earned it some national recognition. In September, Reggie Moore, the office’s director, sat on a panel for a rare congressional hearing on community gun violence, where he shared the Blueprint with the House Judiciary Committee as a model on which they might build a nationwide violence reduction program.

But despite the federal endorsement, Moore has struggled to convince Wisconsin’s GOP-controlled Legislature to buy in — literally. At present, the program is funded exclusively by city grants, which, despite doubling to roughly $400,000 for the 2020 fiscal year, still only pay for a staff of 10 outreach workers for the Blueprint’s central engine, 414LIFE — not nearly enough to service all of Milwaukee’s afflicted communities.

In response, Moore has partnered with State Representative David Bowen, a Democrat from Milwaukee, to draft a proposal for a statewide violence intervention and prevention fund. The fund would mirror similar programs in place in California and Maryland, and provide grants to city governments and other municipalities to fund violence intervention work. Just this week, Moore gave a briefing to the state Legislature on the types of programs such a fund could make possible. But on Wednesday, just an hour before the Molson Coors shooting, Republican Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald doubled down on his party’s unwillingness to consider new measures to address gun violence. “A lot of the provisions that are in place already, people are satisfied with,” he said.

The statement confused Moore and other Milwaukee violence prevention workers interviewed for this story. City residents would welcome a bigger investment in community outreach work, he said. “Violence prevention work is smart on crime, public safety, economic development, mental health,” Moore said. “We know what works.”

Bowen echoed this sentiment, questioning why Republican state legislators, who were so quick to express their profound grief for Wednesday’s tragedies, have been relatively silent on the more regular daily killings his constituents face every day. His proposal for a violence intervention fund, he said, is “an opportunity not just for Milwaukee, but also statewide to partner with folks on the local level and say, If we gave you resources, what would you do with [them]?” To ignore such a proposal, he added, would fly in the face of basic conservative principles about shifting responsibility to the local level and reducing costs.

Bowen plans to introduce the legislation at the start of Wisconsin’s next legislative session, in January 2021, but will make it public next week. He and Moore expect that the Molson Coors shooting will inspire a new wave of enthusiasm for gun reform at the state Capitol. They say they will fight to ensure solutions to community violence are included in the push.

“We definitely support extreme risk protection orders and universal background checks, but at the same time we have to have funding on the menu as well,” said Moore. “The Blueprint has the solutions — now what we need is champions at the state level [to support them].”