This post has been updated with data from the FBI's 2020 Crime in the United States report.

The U.S. murder rate is often regarded as one of our country’s vital signs: Are Americans more or less safe than last year, when it comes to their odds of meeting a violent end?

But misinformation abounds. Is the murder rate really “the highest it’s been in 45 years,” as claimed by then-presidential candidate Donald Trump? (No.) Is Chicago America’s murder capital? (Also no.)

Because the vast majority of American homicides are committed with guns, both the national murder rate and the more relevant citywide and neighborhood murder rates — about which, more below — frequently figure into our reporting at The Trace. In this guide, we’ve collected the most up-to-date statistics on murders in America, as well as the critical context that often gets missed.

A surge in violence during the pandemic reversed decades of progress

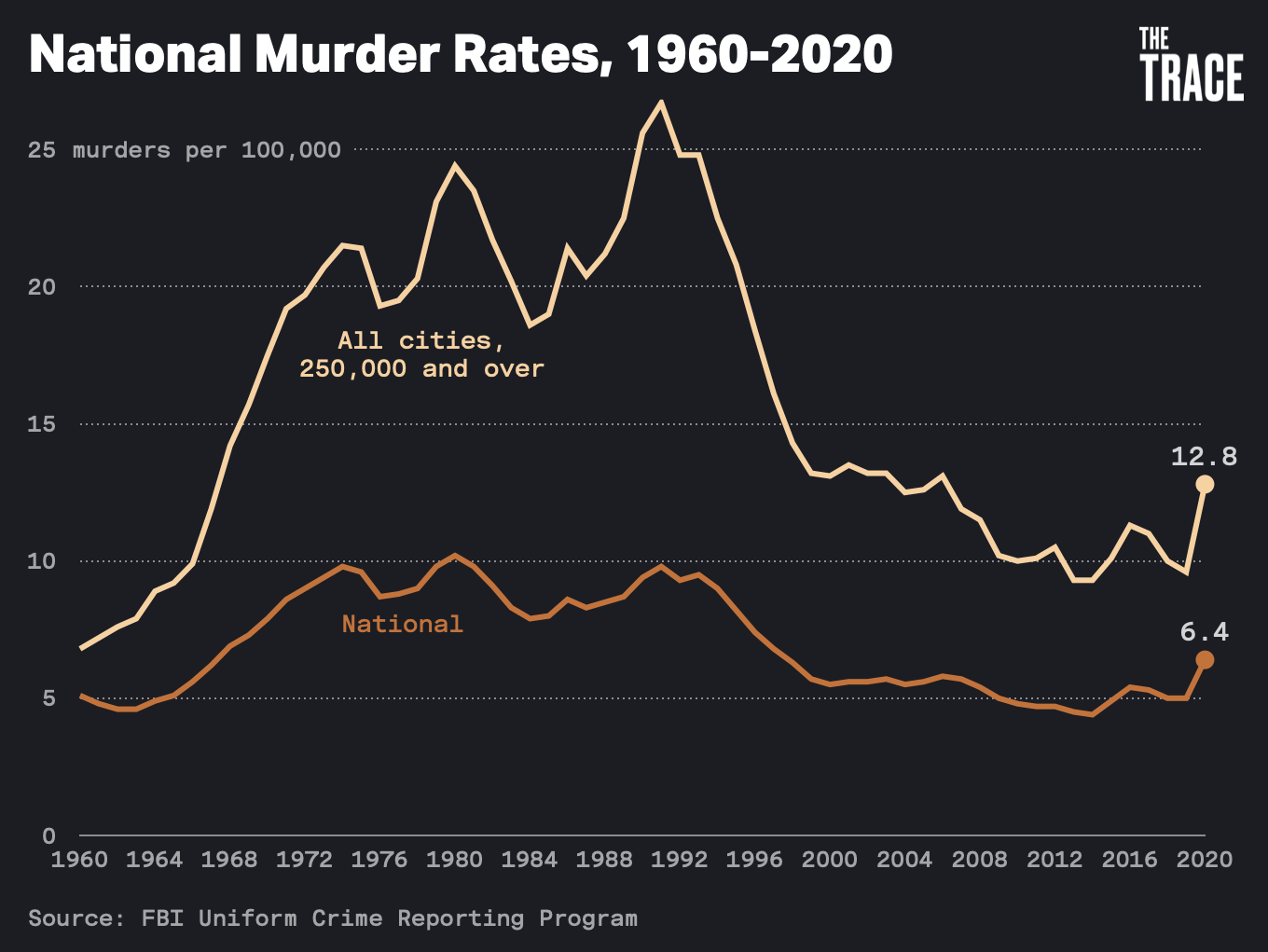

The long-term trend is clear: America is a much less murderous place than it once was. But it didn’t seem that way in 2020, when a wave of gun violence began in tandem with the coronavirus pandemic. Cities across the United States reported a rise in murders last year, and newly released FBI data has clarified the national picture: the murder rate rose by 29 percent in 2020, the largest relative increase since national data collection began in 1960. It now stands at 6.4 murders per 100,000 people, the highest rate since 1998. In cities with more than 250,000 residents, the rate rose by 33 percent, to 12.8 — a level not seen since 2006. The data also reveals that guns were used in 77 percent of murders, the largest share ever.

In many cities, the 2020 spike was even more dramatic. The murder rate increased by 98 percent in Milwaukee, 75 percent in Cleveland, and 52 percent in Memphis, with each city recording its highest level since at least 1990.

Despite this acute and ongoing surge, long-term data shows that murders are still well below the peak rates in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. But the pandemic violence surge marks an alarming reversal of 25 years of relatively steady improvement in the nation’s murder rate.

How U.S. cities stack up

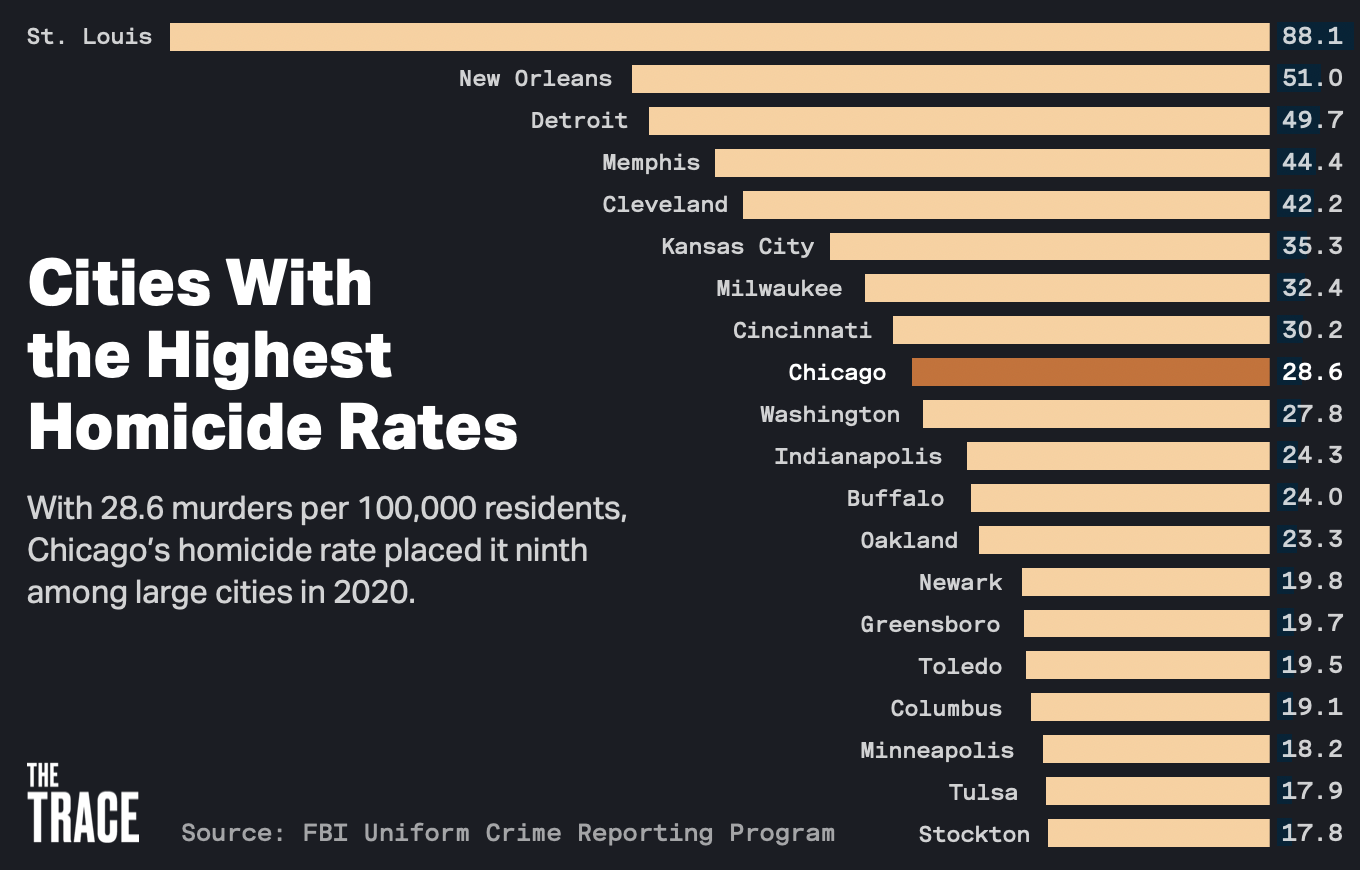

There is no city more synonymous with violence in the United States than Chicago. The Reverend Michael Pfleger, a prominent anti-violence activist and pastor on the city’s South Side, has described his city to reporters as “the poster boy of violence in America.”

To be sure, Chicago has a high number of murders: the city often records the highest absolute total killings each year. But as The Trace has noted, the data tells us that Chicago’s murder rate is nowhere near the nation’s worst. On a per capita basis — murders per 100,000 residents — the city regularly experiences fewer killings than places whose murder rates get far less national attention, like Kansas City, Missouri, or Cleveland.

“Because Chicago has so many people, it can get a murder every day, and that gets people’s attention,” John Pfaff, a professor of law at Fordham Law School, told The Trace. “When you focus on numbers, not rates, Chicago ends up looking worse because you forget just how big a city it is.”

If some scholars of crime had their way, discussions of murder rates would focus not on cities, but on the few urban neighborhoods battling vastly disparate murder levels: Travel a few city blocks, and rates of violence can fluctuate dramatically.

The phenomenon is captured by the term “murder inequality,” a coinage of the young urbanologist Daniel Kay Hertz. Writing for The Trace, Hertz stressed that looking at smaller geographical areas paints a more accurate picture of the relative threat of violence that individual Americans face and can make prevention strategies more effective.

In 2016, five police districts overseeing only 8 percent of Chicago’s population recorded around 32 percent of its murders. Two Chicago neighborhoods, Burnside and Fuller Park, counted a rate of more than 100 killings per 100,000 people. People living in them were nine times more likely to be shot in their neighborhood than in the city’s safest quarters.

“Just like income, education and other metrics of social advantage, violent gun crime varies even more within American cities than between them,” Hertz wrote.

The problem of murder inequality is not unique to Chicago. In St. Louis, most killings are concentrated in neighborhoods like Greater Ville and the adjacent JeffVanderLou, which sit just a few miles from the city’s downtown. The same disparities exist for gun violence overall. Forty percent of non-fatal shooting incidents in 2017 occurred in only 10 of St. Louis’s 88 neighborhoods, according to police data.

The effects of city geography

A city’s borders can have a dramatic effect on its murder rate. St. Louis, which has topped the ranking of major city murder rates since 2014, consists of just a tight urban core, with a population of around 300,000. As crime analyst Jeff Asher notes in The New York Times, only 11 percent of the St. Louis metro area’s overall population resides within city lines, which yields a population-adjusted murder rate that is higher than it would be if the city’s borders included more of its surrounding suburbs. In contrast, many other American cities encompass parts of the less dense and less violent areas outside their centers, lowering their murder rates.

If you compare 2018’s murder rates of major metro areas, rather than cities, St. Louis falls from first to fifth, behind Memphis, New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Baltimore. It’s an important caveat to keep in mind when looking at the data in this article, which only ranks cities themselves.

An ignored crime metric: murder inequality

If some scholars of crime had their way, discussions of murder rates would focus not on cities, but on the few urban neighborhoods battling vastly disparate murder levels: Travel a few city blocks, and rates of violence can fluctuate dramatically.

The phenomenon is captured by the term “murder inequality,” a coinage of the young urbanologist Daniel Kay Hertz. Writing for The Trace, Hertz stressed that looking at smaller geographical areas paints a more accurate picture of the relative threat of violence that individual Americans face and can make prevention strategies more effective.

In 2016, five police districts overseeing only 8 percent of Chicago’s population recorded around 32 percent of its murders. Two Chicago neighborhoods, Burnside and Fuller Park, counted a rate of more than 100 killings per 100,000 people. People living in them were nine times more likely to be shot in their neighborhood than in the city’s safest quarters.

“Just like income, education and other metrics of social advantage, violent gun crime varies even more within American cities than between them,” Hertz wrote.

The problem of murder inequality is not unique to Chicago. Last year in St. Louis, most killings were concentrated in neighborhoods like Greater Ville and the adjacent JeffVanderLou, which sit just a few miles from the city’s downtown, and each recorded a murder rate of 162. The same disparities exist for gun violence overall. Forty percent of non-fatal shooting incidents in 2017 occurred in only 10 of St. Louis’s 88 neighborhoods, according to police data.

See how your city stacks up

Below, we’ve compiled historical murder rates for major American cities, using figures they provided to the FBI. You can sort the rankings by year, and search for your own city to see where it ranks.

Murder rates of major U.S. cities

Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports. Interactive: Daniel Nass.

Murder rates — and especially the neighborhood-level rates that yield murder inequality — are one metric for understanding America’s gun violence crisis. But because homicides comprise only roughly a third of all gun deaths, it is important to know the data on gun suicides, which account for the other two-thirds firearms fatalities, and are rising in 20 states. It’s also valuable to look at how gun violence harms specific populations, like domestic abuse victims and children. For a single overview of the most salient statistics about gun violence — and potential interventions — please see this guide.