News cameras filmed Martinez Smith-Payne as he lay recovering in a bed at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. He was 10 years old, and had discovered a firework in a barren field in the northern part of the city. After he lit the fuse, it exploded in his left hand, blowing off all of his fingers except the thumb. When he later appeared on television, his destroyed hand was wrapped in a ball of gauze, and his eyes were covered with a mask, partially concealing his delicate face. Martinez was a small, frightened boy, but for his mother, Frances Smith-Woods, he made a show of bravery. “He was telling me it’s ok,” she said at the time. “I guess he didn’t know the severity of it.”

Three years later, on November 28, 2015, Martinez and two of his friends — Ernest Williams, 14, and another boy, who was 11 — climbed onto their bicycles and set off under a full moon from the St. Louis neighborhood of Walnut Park East, one of the most dangerous areas of a city with the highest homicide rate in the United States. Martinez, Ernest’s little cousin, was then 13. He had small ears and sharp cheekbones. He liked Hot Wheels cars, Nick Cannon, and The Polar Express. He weighed 89 pounds. His earlier accident had not raised his threshold for pain. When he received shots at the doctor, multiple family members had to hold him down.

Like almost everyone in Walnut Park East, the three boys were African-American. They rode their bikes past rows of dilapidated, single-story structures with broken gutters and broken windows, sagging porches and peeling paint. Some homes appeared to list heavily, as if about to topple over. Others were boarded up and empty, with signs posted by the city that said “No Loitering.”

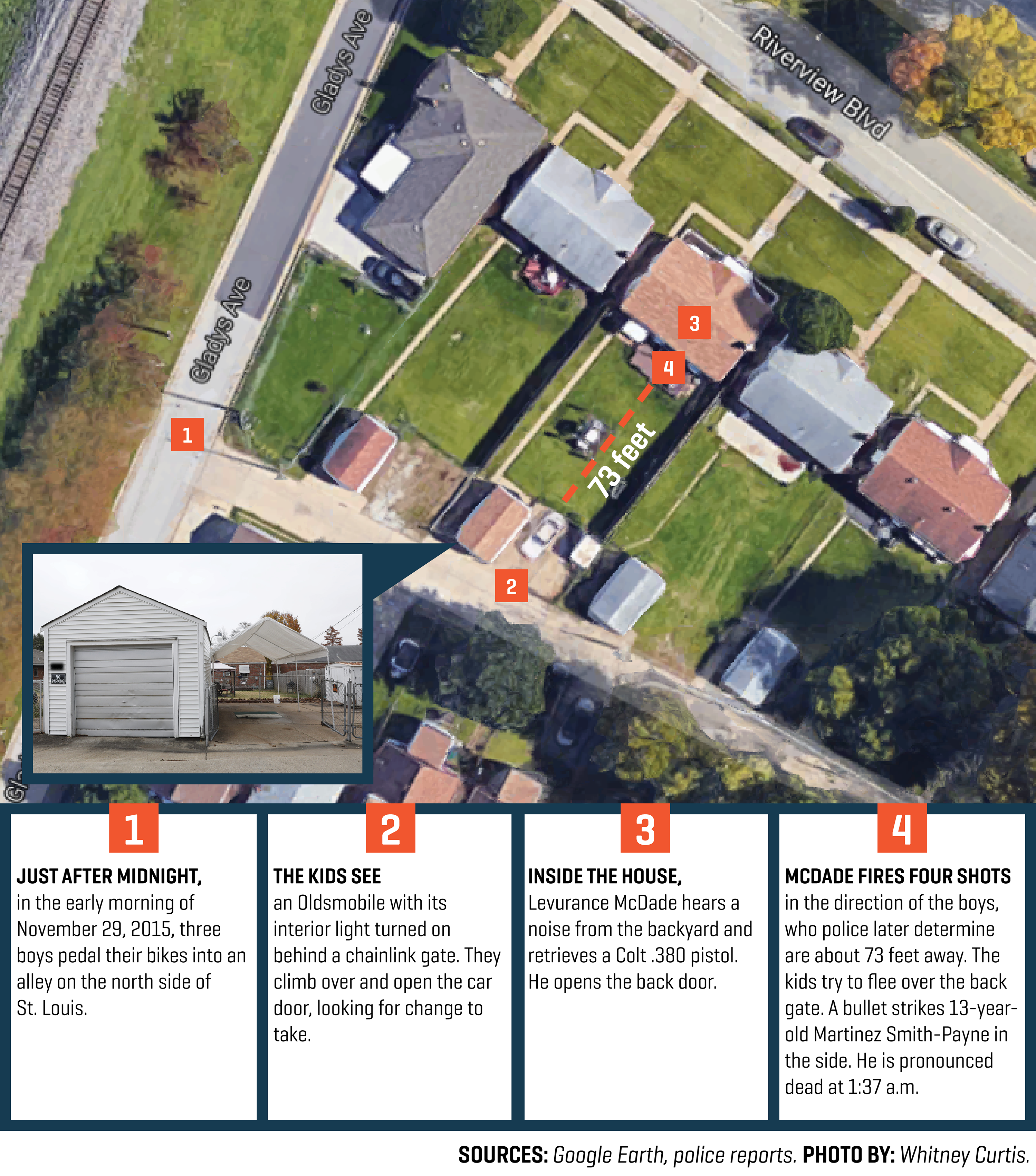

As the night wore on, the boys reached Riverview Boulevard, a main thoroughfare where the homes are made of red brick and are in better condition than those in Walnut Park East. They pedaled into a concrete alley that ran behind the houses, softly illuminated by overhead lights.

Shortly before 12:45 a.m., the boys came upon a blue 1991 Oldsmobile sedan, parked in a carport behind a closed chain link gate, next to a white garage. The interior light had been left on, and it caught their attention. They were children with little access to spending money, and thought there might be some in the vehicle. They set down their bicycles and hopped over the gate.

The owner of the car, Lervurance McDade, was a 60-year-old black man who worked at Taco Bell. He was in his bathroom when he heard a rattling sound and looked out a window. There was movement. He retrieved a Colt Hammerless .380 semiautomatic pistol he had purchased from a friend, switched on a light attached to the garage, and opened the back door.

Outside, Ernest, the 14-year-old, stood watch by the driver’s door while Martinez and the other boy, whose name has not been released, poked around in the car. They spotted a container in the center console. Inside were four dimes and 15 nickels.

McDade peered into the night. From where he stood, the boys were more than 70 feet away. Another chain link fence, this one separating the carport from the backyard, stood between McDade and the unarmed children.

Seeing the boys, McDade yelled, according to an account he gave to police. Then, as they fled back over the gate and into the alley, he fired four shots in their direction.

Two of the boys landed safely. Martinez collapsed onto the concrete and called out for help. He had been shot in his side.

Ernest came over to Martinez as blood pooled onto the ground. He called 911 and police and paramedics arrived at the scene. Martinez told one of the responding officers that he’d gone into McDade’s yard to recover a basketball. Ernest said no, that wasn’t true; they’d been rifling around in the car.

An ambulance transported Martinez to St. Louis Children’s Hospital, his second visit there for an emergency. This time, he would not get the chance to speak to his mother and assure her everything was fine. He was pronounced dead at 1:37 a.m.

When police did their first interview with McDade, he told them that he was legally barred from owning a firearm because of a felony conviction two decades earlier. After handing over the weapon, he was arrested and taken to homicide headquarters, downtown. Gun violence had gotten so out of control in St. Louis that nearly half of the city’s 40 trial prosecutors were now dedicated full time to covering the epidemic.

It was now hours into the morning of November 29. Don Tyson, a veteran city prosecutor, had made his way over to the department. A stout, gray-haired man whose glasses tend to rest on the edge of his nose, Tyson is a member of the National Rifle Association and has taken part in well over 200 trials. The city’s homicide crisis — 188 people were killed in St. Louis in 2015, 178 of them with guns — was constantly on his mind, and he felt there was nothing worse than when the victim was a child. He watched from another room as detectives questioned McDade.

McDade said he had left his car unlocked as a precaution: In St. Louis, thieves were known to smash windows to steal change and other items, so it was common to put a club on the steering wheel and leave doors unsecured. He claimed he had never intended to shoot anyone, and only wanted to protect himself and his property. The intruders, McDade remarked, seemed to be headed in his direction. He admitted that he did not see any of the boys produce a weapon, but, as the police report stated, he “thought the males might be armed.”

McDade had used an illegal gun to shoot at three unarmed kids some 70 feet away from his home, killing one of them. In other places, and at other times, this would be the kind of reckless behavior that could at minimum lead to a charge of manslaughter. But Missouri’s legislature, along with those in many other states, had adopted a statute known as the “castle doctrine,” which says people can use deadly force to defend themselves on their property, so long as the individual “reasonably believes” he or she is about to be attacked. The principle is rooted in an incident from 1604, when an officer of the crown forced his way into the house of an Englishman named Semayne. According to Stand Your Ground, a forthcoming book by the Harvard historian Caroline Light, the British attorney general overseeing the case declared that “the house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress.”

In the last decade, gun rights groups — especially the NRA — have pushed to expand legal protections for people who shoot in self-defense. In 2005, Florida enacted a castle doctrine statute, crafted by the NRA, that permits people to not only kill home intruders, but also anyone they believe will do them “imminent” harm in any location they have a right to be. Soon after, the American Legislative Exchange Council, a powerful conservative coalition of legislators and corporations, used the Florida statute to craft a model bill, which it called the “Castle Doctrine Act.” ALEC worked with the NRA on the initiative, and advocated for it around the country. In 2006, 13 states adopted a version of the statute. By 2012, the number had grown to 22.

After the killing of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, in 2012, the provision of the new laws that applied to public spaces became widely known as “stand your ground,” after a phrase that appears in the statute. Martin’s death brought national scrutiny to the provision’s effects. In 2012, a Tampa Bay Times investigation found that, since the law was enacted in Florida, almost 70 percent of those using “stand your ground” as a defense had gone free. The newspaper also found that it was much easier to mount a successful defense if the victim was black. After studying the issue, the American Bar Association recommended that legislatures repeal broad self-defense statutes “because empirical evidence shows that states with statutory stand your ground laws have increased homicide rates.”

Don Tyson’s challenge, as he picked up his new case in St. Louis, was to determine whether the fear that led McDade to pull the trigger was reasonable and if it would be possible to prove otherwise.

Missouri’s first version of the castle doctrine, passed in 2007, provides heightened legal protections for people who shoot in self-defense if they are in their home or vehicle. Passing the law was a top priority for the NRA. Kevin Jamison, a weapons and self-defense attorney in Gladstone, a suburb of Kansas City, says a law was needed to protect people who acted to protect themselves or their families from harm.

“Basically, you could only shoot someone if you caught him in the act of crawling through your window,” he said.

Three years later, the Missouri legislature expanded the castle doctrine to include all of a person’s property. It was the updated statute that might protect Lervurance McDade.

“We have one of the most expansive castle doctrine laws in the country,” said Anders Walker, a constitutional law professor at St. Louis University. “Any prosecutor is going to think twice before prosecuting someone who shot an intruder on his property.”

Two weeks after watching McDade’s interview with the detectives, Tyson visited the crime scene. He was accompanied by Jennifer Joyce, the St. Louis Circuit Attorney, an elected official in her 15th year on the job.

A courtroom veteran with a plucky persona belied by weary blue eyes, she had lived in St. Louis all her life, and was publicly planning on stepping down when her term ended in 2016. It was ultimately up to her to decide what, if any, charges McDade would face. As the head of the 150-person office, it was unusual for Joyce to make excursions to crime scenes, but this case compelled her to take a more direct role.

“I wanted to see for myself the physical layout of everything, be in it, understand how this transpired,” she said.

As the attorneys examined McDade’s property, Tyson focused on the space around the car. The Oldsmobile was parked parallel to the garage, with its front facing the alley. The rear bumper, which bore damage from a bullet, faced where McDade had stood at the back of his house, holding his gun.

Martinez was on the passenger side as he rummaged for change, and Tyson observed that there was hardly any space between the side-view mirror and the garage wall. For Martinez to get away, Tyson reasoned, the boy may have had to first dash around the rear fender — and in the direction of McDade and his house — before turning back toward the alley. If that was the route Martinez had taken through the shadows of the carport, it might have given McDade the impression that he was being charged.

After they inspected the crime scene, the prosecutors interviewed McDade’s neighbors along Riverview Boulevard. “What we found was that the neighborhood was having a great deal of problems,” Tyson said. “Especially late at night. People breaking into cars, houses, and garages. The entire neighborhood was on edge.”

Rachel Smith, another veteran prosecutor assigned to the case, said she spoke to an alderman from the area after the shooting.

“He said, ‘I want you to know that everyone in the area knows that kids are carrying guns. That guy was scared,’” she said, adding, “If everyone believes everyone else is armed, it doesn’t make the city safer; it makes people more willing to shoot.”

About a week before Christmas, Joyce convened a meeting in her office with the attorneys who had participated in the investigation. A framed picture of a black St. Louis teenager brandishing a firearm sat on a table. The photograph had made the rounds on social media. Joyce saw in the photo the hungry vortex of the city’s gun culture, swallowing up everyone it touched.

Tyson characterized the discussion as “very collegial.” Everyone agreed on the course of action. They would bring against McDade a single charge of wrongfully possessing a firearm.

“The layout seemed to corroborate his story,” Tyson said. “All Mr. McDade knows is that he has three guys in his locked yard, breaking into his car. And the first move he sees is towards him.

“What’s reasonable comes down to a calculus by us. We’re not going to require someone to be shot or shot at before he clears the hurdle of reasonable fear.”

Last month, the terms of McDade’s probation were set after he agreed to plead guilty to the gun charge. He won’t spend any time in prison. After the case was closed, he told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that he just wanted to put the episode behind him.

“All of us are very concerned about gun violence in St. Louis,” Joyce said. “Particularly when a young person is killed like that — if there was a way to prosecute that case, we would do it. We’re not afraid of tough cases.”

McDade did not respond to requests for an interview. On a recent visit to his home, there was a sign on his front lawn seen frequently around St. Louis. “We must stop killing each other,” it says.

Prosecutors don’t like to hypothesize about what they might do differently if a statute didn’t exist. The lawyers in the St. Louis office who handled the McDade case say they are confident they made the right decision, given the specific facts presented to them.

Still, Joyce makes little secret of her dislike for the castle doctrine and disgust with Missouri lawmakers, who over the last decade have radically rewritten the state’s firearms laws.

“I’m generally troubled by the steady stream of legislation that has eased restrictions on guns,” she said.

In September, politicians in the state House and Senate overrode the governor’s veto of a sweeping new gun bill. One plank of the legislation removed the requirement to obtain a permit before carrying a concealed weapon. Another added yet more protections for gun owners who injure or kill for putative protection, making Missouri the first state to pass a “stand your ground” law since Trayvon Martin’s death. As of October 14, the ambiguous standard governing the use of deadly force now applies anywhere a person has a right to be, not just within certain boundaries, such as the fencing around McDade’s property.

The NRA fought for these laws. Its influence over the heavily Republican legislature is hard to overstate. Seventy percent of Missouri state lawmakers have received a grade of A- or better from the group.

Earlier this month, I met with Joyce and some of her team members in their downtown office, just blocks from the Gateway Arch that greets visitors traveling through the city from the east.

“Soon we’ll have guns at birth,” Joyce said. “I don’t know where we go from here. It doesn’t look good.”

She sighed and added: “Who the hell is the NRA that they’re grading our politicians? Who’s the NRA that they’re holding such sway? Why are they running my state? I gotta hand it to them—they’re masterful, like Lex Luthor.”

Joyce was angry that the rural and suburban areas of the state were not only unwilling to address the city’s gun violence problem, but, as she sees it, actively making it worse. Aside from the immense challenges posed by Missouri’s broad self-defense laws, measures that make it easier for people to carry guns mean that more of them will show up in her city.

“But when we go to the legislature to talk about the loss of life we’re seeing, we sound like the teacher in Charlie Brown,” she said. “They really don’t care.”

Before I left the prosecutor’s office, I was shown some of the images that Joyce’s office had collected during her tenure. Like the framed picture she kept on her table of the boy holding a gun, these other photos were culled from social media. Like that photo, they showed St. Louis children —teenagers, or younger — standing, posing, dancing with powerful semi-automatic weapons.

St. Louis’s police chief, Sam Dotson, fears “stand your ground” legislation could have dire implications for his city’s public safety.

“Suddenly it’s, I’m skeptical of everybody, and if you cut me off on the road, I’m going to assume you have a gun and you’re going to shoot me, so I’m going to shoot you,” he said.

“We’ve created an environment that is ripe for more situations like the one that resulted in that 13-year-old boy’s death. There are going to be more situations where shootings are going to be questionable. The decisions we’ve made regarding gun laws are now starting to impact us.”

Research supports his concern. Studies have found that states that implement “stand your ground” have experienced rising gun homicide rates. One paper, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in November, determined that in the nine years after Florida instituted its “stand your ground” law, the state’s gun homicide rate had soared 31.6 percent.

On a frigid, blustery December day I visited Frances Smith-Woods, the mother of Martinez Smith-Payne. She was staying at the home of Demetria Evans, the boy’s stepmother, who lived in the southern part of St. Louis. The two had grown close over the years. Martinez’s father died in 2014, and they relied on each other for emotional support.

Evans’ cheerful home is covered wall-to-wall in framed photos of family members. Wrapped Christmas gifts were neatly piled on the floor, and Christmas music played on a stereo. Smith-Woods is a shy woman of 41. She told me that after the shooting, she could no longer tolerate staying in her own home, so she and her 12-year-old son, Jahiem, left it behind.

“Martinez wanted to be a chef,” she said, sitting beside me on a couch. “The morning before he died, he cooked fried chicken, waffles, and eggs. Then he went to his friend’s, where he’d gone many times. He was having a sleepover.” Smith looked at her knees. “He went out the door. I didn’t see him alive after that.”

Evans stepped into the room. A sturdy woman of 49, she had tattoos along her collarbone and a gold tooth that glimmered as she spoke. She took a seat on an arm of the couch and began to cry.

“Martinez is irreplaceable,” she said. “He was a wonderful little boy. He loved to dance. If he caught a beat, he would stop, drop, and shake a tailfeather.”

She wiped her eyes with the back of her hand.

“Don’t remember Martinez for what they said about him. Remember him with a smile on his face. Remember he was a kid, not an adult.”

Evans composed herself.

“We understand what he did was wrong,” she said. “But to take his life for going through a car?”