Despite the downward trend in violent death rates across the United States, suicide rates for men and women have steadily increased for the past 15 years.

Find Support

Help is Available 24 Hours a Day

Crisis Text Line

Text 741741

The Veterans Crisis Line

988, press 1, or text 838255

Help Someone Else

Understand warning signs.

The statistics are bleak. Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in America. From ages 10 to 34, it is the second leading cause, claiming more lives than homicide or heart disease. In 2017, the most recent federal data shows, 47,173 people in America took their own lives. Between 1999 and 2017, the suicide rate jumped 33 percent.

Our country’s suicide problem is also a gun violence problem. Firearms are involved in about half of all suicide deaths, yet this connection is often overlooked. Gun advocates have been slow to acknowledge the extra risks posed to suicidal people who have easy access to a firearm. Some insist that gun suicides should not be counted as gun violence, even though they account for 60 percent of gun deaths.

“Suicide is almost entirely ignored within the discussion of guns in the United States,” wrote researcher Michael Anestis, in his book Guns and Suicide: An American Epidemic. He noted that when discussing gun deaths, most news media stories and politicians fixate on homicides or accidental shootings. “With the national suicide rate climbing annually, I would argue that continuing to ignore suicide when discussing guns is costing thousands of American lives every year.”

The Trace has prepared this statistical guide to illuminate the links between guns and suicide and to identify some solutions that could save lives.

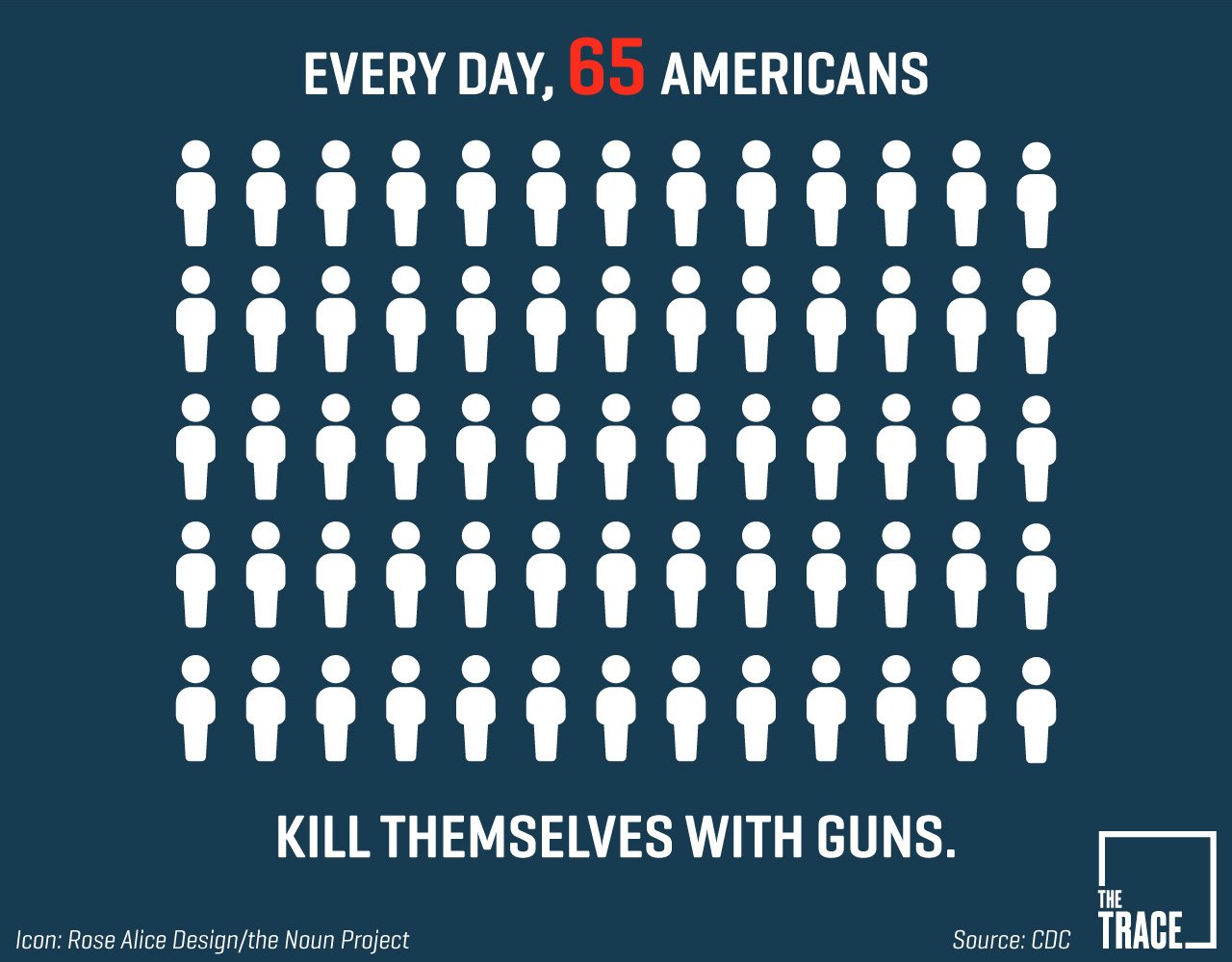

1. 65 people kill themselves with a gun every day.

In 2017, more than half of suicides (23,854, to be precise) were carried out with a gun, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Though the typical victim of a gun homicide is a young, black male, the typical suicide victim is a middle-aged white man living in a rural area. In 2017, white males accounted for 78 percent of suicides; overhwelmingly, they used a gun.

No group is immune from the risks of suicide. About 2,000 people aged 75 to 84 killed themselves with a gun in 2017 — averaging more than five deaths per day. Teenagers are also at risk: Among those aged 15 to 19, 1,110 people killed themselves with a gun that year — averaging three such deaths per day.

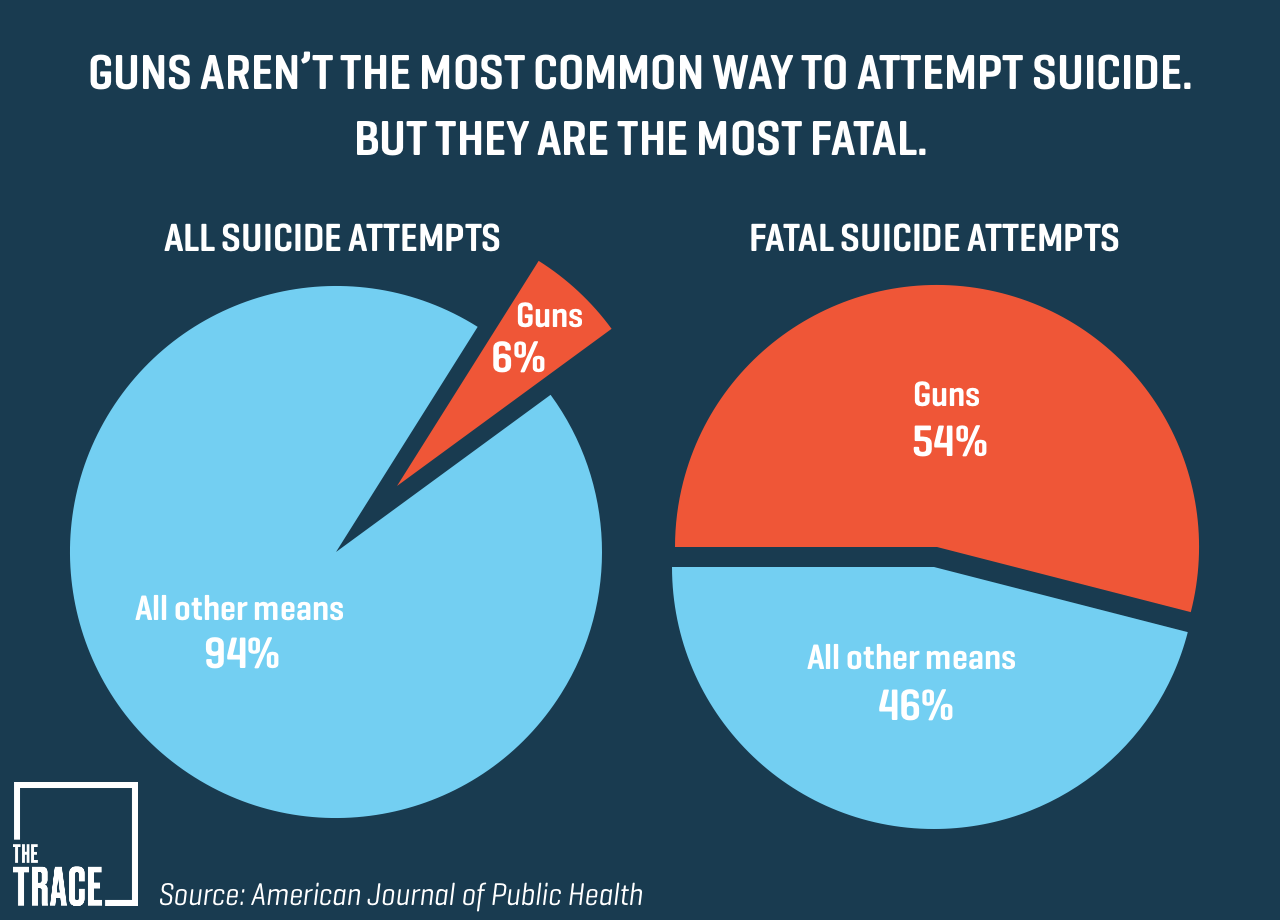

2. Suicide attempts with a firearm are lethal about 85 percent of the time.

One explanation for why men die by suicide at such high rates is that they are less likely than women to seek mental health treatment. Another is that men are more likely to use a gun. Women attempt suicide more often than men do, but they typically opt for pills or poison, which are substantially less lethal.

Guns are a devastatingly effective means of ending one’s own life: Suicides attempted with a firearm are lethal about 85 percent of the time. Firearms suicide accounted for only 1 percent of nonfatal attempts, but 54 percent of fatal attempts in one study that examined hospital data from eight states. For comparison, drug or poison overdosing accounted for 71 percent of attempts but only 12 percent of fatalities.

3. About 90 percent of people who survive suicide attempts don’t go on to kill themselves.

One of the biggest myths about suicide prevention is that people who survive a suicide attempt will simply find another means, said Dr. Matthew Miller, the co-director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center.

“You’ve got people saying, ‘Oh, if he didn’t shoot himself, he would have jumped off a tall building or found another way to kill himself.’ It’s not illogical, it’s just wrong — wrong in the face of facts that strongly say otherwise,” he said.

According to Catherine Barber, a suicide expert and Miller’s Harvard colleague, research shows that between just 5 and 11 percent of people who attempt suicide will go on to kill themselves. Barber cited one study that followed people who attempted suicide by jumping in front of a London underground train and survived. “Even among these very serious attempters, 90 percent did not go on to take their lives in later years.”

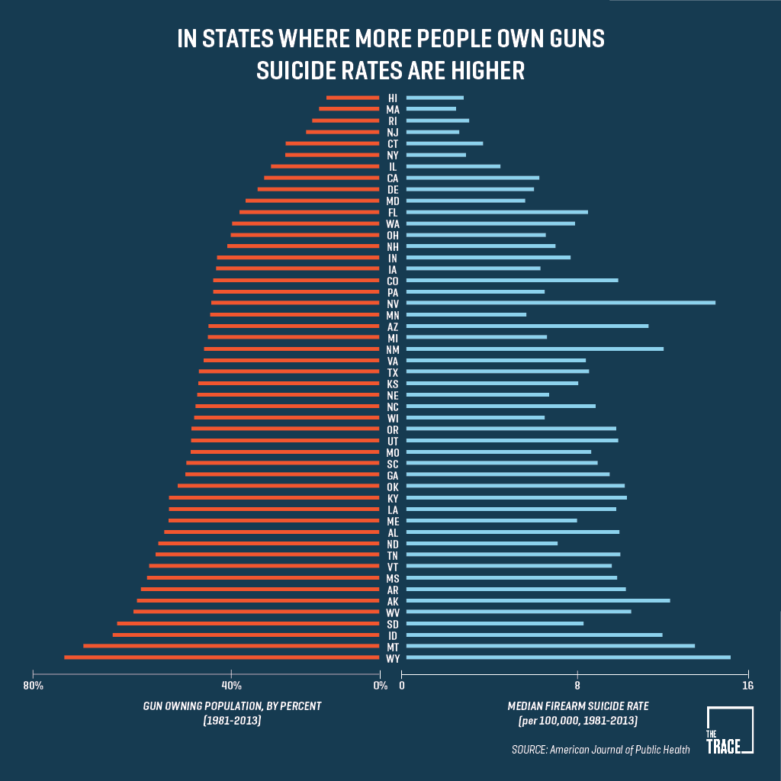

4. States with the highest gun ownership rates have the highest suicide rates.

A sweeping study published in July 2016 in the American Journal of Public Health, found that for every 10 percentage point increase in a state’s gun ownership rate, there was an associated increase of 3.3 firearm suicide deaths per 100,000 among men, and a .5 increase in firearm suicide rates among women.

Dr. Michael Siegel, a professor at Boston University School of Public Health, and his colleague, Emily Rothman, examined 33 years of data from all 50 states to reach their conclusions. For men, average gun suicide rates were as low 4.2 per 100,000 in Massachusetts, and as high as 26.1 in Wyoming, a six-fold difference. The study controlled for other factors that could be used to explain a state’s suicide rates, such as unemployment or alcohol abuse. Over the 33-year study period, Wyoming averaged both the highest gun ownership rate and the highest gun suicide rate in the country.

Wyoming is part of a cluster of Western states including Nevada, Colorado, and Idaho that have so consistently had higher-than-average suicide rates that some researchers refer to this region as the Suicide Belt. The nine states with the lowest rates of gun ownership — including California, Rhode Island, and New Jersey — have the lowest rates.

5. A gun in the home increases the risk of suicide.

Research shows that the presence of guns in a home correlates with higher suicide rates.

One explanation: Suicide is often an impulsive act, with the person in distress opting for what seems like the easiest obtainable means. Guns are more lethal than any other instrument; if kept close at hand, a firearm is the method most likely to be used.

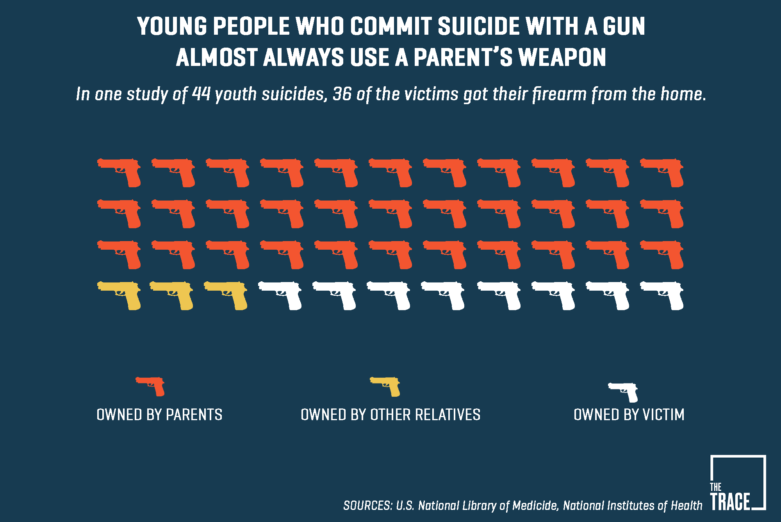

Two studies of youth access by researchers at Harvard are instructive. One found that at least 82 percent of teens who ended their lives with a gun had used a weapon belonging to someone in their home. Another, using data from a 22-year period, determined that a 10 percent drop in the percentage of households owning guns was associated with an 8.3 percent decline in overall suicide rates for young people.

Barber, the Harvard researcher, explained that the studies show the vital role that the safe storage of firearms can play in preventing suicide, especially among young people. “Many parents are careful about keeping their guns locked when their children are small and are less careful when they are teenagers — precisely the time when youths’ risk of gun misuse actually goes up, not down,” she said.

6. Keeping guns away from suicidal people can save lives.

One intervention that can have a profound effect on saving lives is blocking suicidal individuals from accessing guns during a time of crisis, by removing them, storing them out of reach, or convincing gun owners to voluntarily surrender their weapons.

“Suicide is really hard, and if you make it harder, logistically, it’s much less likely to happen,” said Anestis, the suicide researcher.

Many public health efforts, including several spearheaded by Harvard’s Means Matter Campaign, are focused on convincing suicidal people to store their guns away from home, or to ask a trusted friend or family member to hold onto their weapons when they or a family member are in crisis.

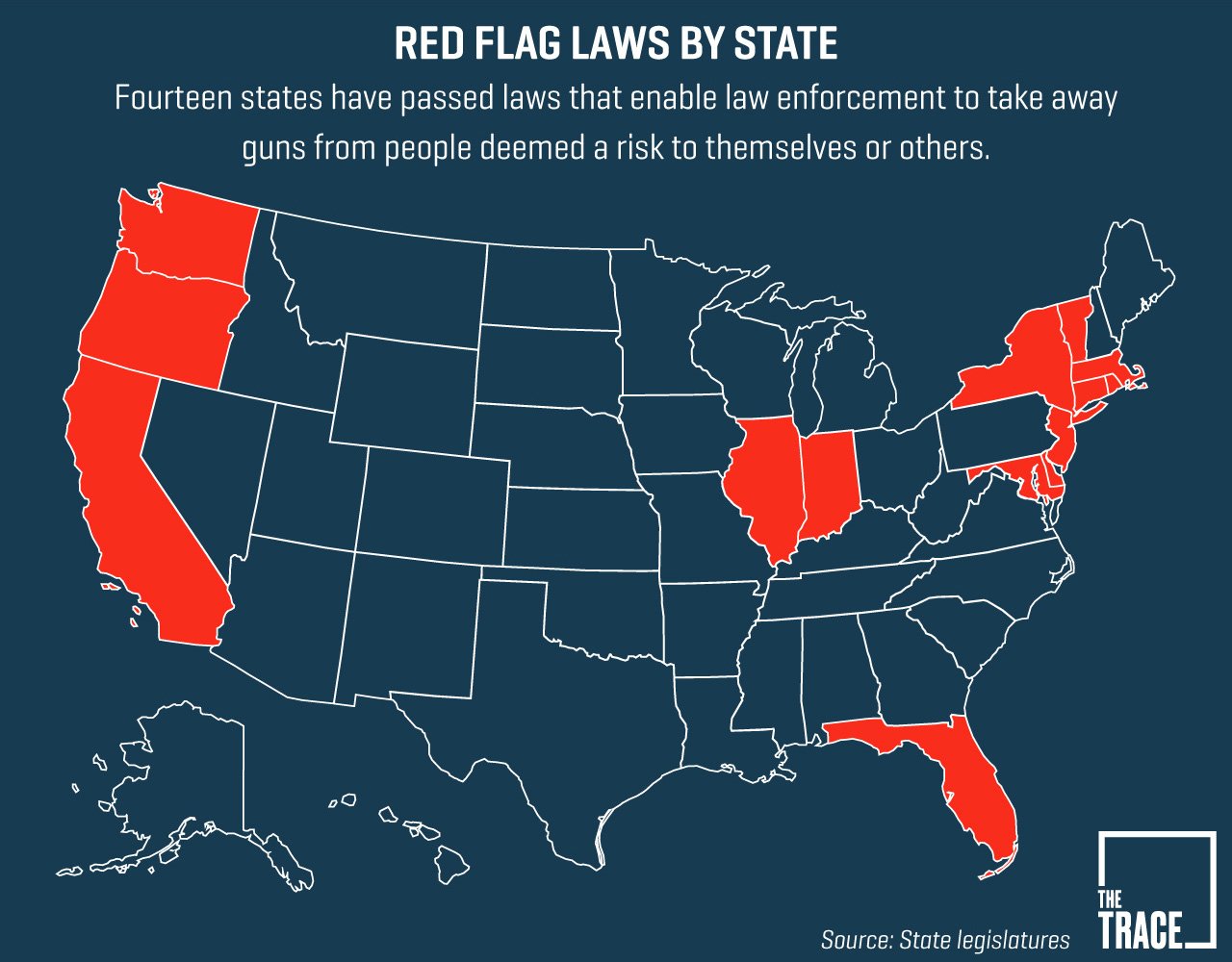

At least 14 states and the District of Columbia have so-called red flag laws, which allow family members or law enforcement officials to petition a judge to take guns away from people who pose a threat to themselves or others. In Connecticut, where such a law has been in effect since 1998, police seized more than 2,000 guns between 1999 and 2009. A concern about suicide was the most common reason for seeking a warrant, cited in 46 percent of the cases.

7. The gun-owning community can help to reduce suicides.

Some people buy guns for the explicit purpose of ending their own lives. An examination published in The New England Journal of Medicine looked at suicide rates among California handgun purchasers. It found that the firearm suicide rate increased dramatically in the first week after purchase: to 57 times higher than the statewide rate. Researchers posited that some people bought handguns “with the intention of killing themselves.”

To address this phenomenon, a nationwide program called the Gun Shop Project asks gun store owners and firing ranges to distribute materials about suicide prevention to their clients. One goal is to help gun dealers spot potentially suicidal customers. Another is to reframe the idea of keeping guns away from suicidal people as a firearms safety tenet by making the practice as basic as keeping a gun unloaded when it’s not in use.

While it’s too early to proclaim the program a success, Barber, who helped develop the program, said that early results are promising. In New Hampshire, 48 percent of gun stores opted to display the suicide prevention materials. Most importantly, some gun store owners have credited the program with saving lives. Another initiative from Means Matter helps firearms instructors include a short module on suicide in their firearms training classes.

In August 2016, the National Shooting Sports Foundation, the gun industry’s trade group, partnered with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention on a similar initiative. The program distributed materials to shooting range operators and gun safety instructors across the country, with the goal of preventing nearly 10,000 suicides by 2025.

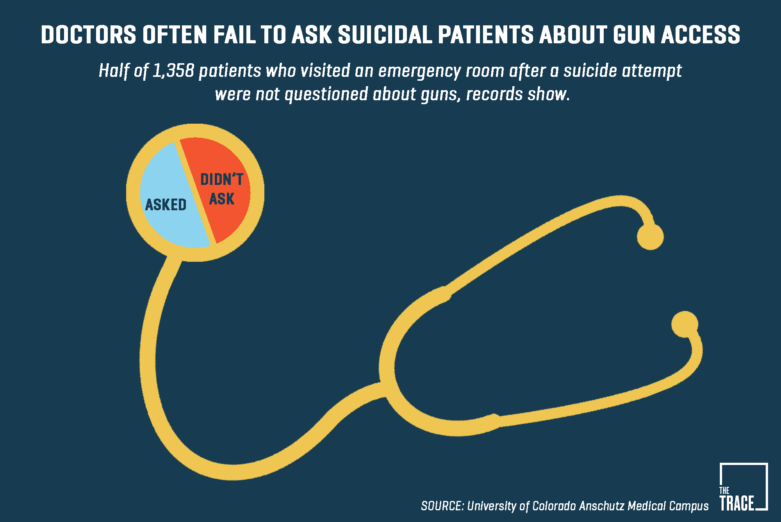

8. Doctors often don’t talk to suicidal patients about guns.

Many health professionals shy away from speaking to their patients about firearms — because they don’t know how to broach the topic, because they don’t want to alienate gun owners, or because they’ve been explicitly discouraged from doing so. In Florida, for example, a 2011 law restricted what doctors could say to their patients about guns, until it was struck down in 2017.

One study from Dr. Emmy Betz, a medical professor at the University of Colorado, found that only 18 percent of patients who visited an emergency room and had been identified as at risk for suicide were asked if they had access to guns, according to their charts.

However, after a series of high-profile mass shootings in the past two years — including in Las Vegas and Parkland, Florida— the medical community has become increasingly vocal about the need for physicians to discuss guns.

Several papers published recently in the Annals of Internal Medicine have urged doctors to talk about guns with their patients, including those who are considered more at-risk for suicide. One encouraged doctors to pledge to discuss guns. Since December 2017, more than 2,200 health care providers have taken the pledge.

“We’re making slow progress,” said Dr. Betz. “There’s a growing discussion and awareness that we should do this, along with the appropriate questions of how to do it best.”

Most Americans, it seems, are open to discussing firearms with their physician. One survey published in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that 66 percent of Americans thought it was appropriate for doctors to talk to patients about gun ownership; 62 percent of gun owners thought the topic was appropriate if children were in the home.

9. Waiting periods for gun purchases have been associated with lower suicide rates.

Several studies have found that laws imposing a delay between the moments when someone buys a gun and when they can bring it home are associated with reductions in suicides.

Federal law doesn’t require gun dealers to impose a waiting period when customers seek to purchase a firearm, so states are left to pass their own requirements, which typically range from 3 to 14 days. Hawaii, which has one of the lowest suicide rates in the country, has a 14-day waiting period.

South Dakota had a two-day waiting period before its law was repealed in 2009. The next year, the state saw a 7.6 percent uptick in its suicide rate, according to research from Anestis. And in the first four years after the law changed, the state saw an 8.9 percent increase in suicide rates.

Anestis also observed a similar trend in Washington, D.C. One year after the implementation of a law extending the waiting period to buy a handgun, the suicide rate decreased 2.2 percent.

10. Personal outreach can make a big difference.

Some experts avoid using the word “impulsive” when discussing suicide.“It makes people think that the suicide came out of the blue, which is rarely the case,” said Barber.

“For a hefty proportion of people who attempt suicide, the movement from thinking about suicide to actually attempting is often rapid,” she said, but noted that the underlying factors are often chronic. Typically, she said, the person has been struggling with a mental health issue or a substance abuse problem.

Some signs that a person is suicidal may be evident to friends and family members. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center hosts a list of warning signs. It includes talking about wanting to kill oneself, obtaining a gun, or changing one’s sleep habits.

Barber advises paying close attention to external circumstances, such as a breakup, a return to prison, or job troubles. “You don’t want to overreact to these things,” she said, noting that many people could be perceived as exhibiting warning signs. “But you do want to reach out and ask how the person is doing, and if they seem to be in a lot of distress, help them find counseling or care if they’re open to it, and help them get their guns, if they have any, out of the picture until things have settled down.”

A moving article published in HuffPost last year, “The Best Way to Save People from Suicide,” underscored how life-saving it can be for suicidal people to feel cared about. The piece noted that in cities all over the world, studies have found that short, regular check-ins — by text, email, or letter — were associated with reductions in suicide attempts.