Throughout the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump has made the case for fearfulness, from violence of both foreign and domestic origin. At his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention on Thursday, Trump declared that “decades of progress made in bringing down crime are now being reversed.”

Earlier in the week, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani described an America under siege, from terrorists, from criminals, and even from protesters. “The vast majority of Americans today do not feel safe,” he said.

Yet despite a torrent of horrific, high-profile events, including a rampage at a gay nightclub and deadly ambushes of police officers in two cities, crime stats clearly show that the “vast majority” of Americans are, in fact, far safer than two decades ago. In 2014, the most recent year for which full data is available, one third as many people reported being a victim of a violent crime as did in 1994, according to a Justice Department crime survey. Less than half as many were murdered.

National rates, however, are also not the best way to understand the risk of crime to typical Americans — partly because they imply that there is such a thing as a “typical American.” In the U.S. in 2016, the relative level of public safety very much depends on where you live, how much money you make, and the color of your skin. A proper understanding of violent crime requires looking at neighborhood rates, which reveal a terrible murder inequality.

As Trump noted in his speech, in many major U.S. cities, violent crime increased last year. The candidate’s rhetoric omitted the fact that rates were down in other cities, and criminologists caution against drawing broad conclusions from single year movements. But the increases in places like Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Houston have been dramatic enough to spark urgent civic conversations and draw the interest of national publications (including this one) seeking answers behind the violence.

Chicago, where I live, is another one of those cities where violent crime, especially gun violence, is sharply up over the last year. While there are mixed feelings here about the attention our violent crime wave has received — and questions about whether that attention helps or just sensationalizes — the attention may represent a welcome shift from coverage that too often focuses on the sensational.

Pushing the spotlight on gun violence in the direction of the cities where most shootings take place is a positive step. Even so, we won’t really understand the issue until we go one step further.

America has an urban gun violence problem only inasmuch as some of its urban neighborhoods are beset by persistent, truly epidemic shooting rates. Those local shooting rates, in turn, yield a disparity in mortality risks that should shock the national conscience.

To understand why all that is true, let’s start with a seemingly straightforward question:

Are you more likely to be shot in Chicago or New York?

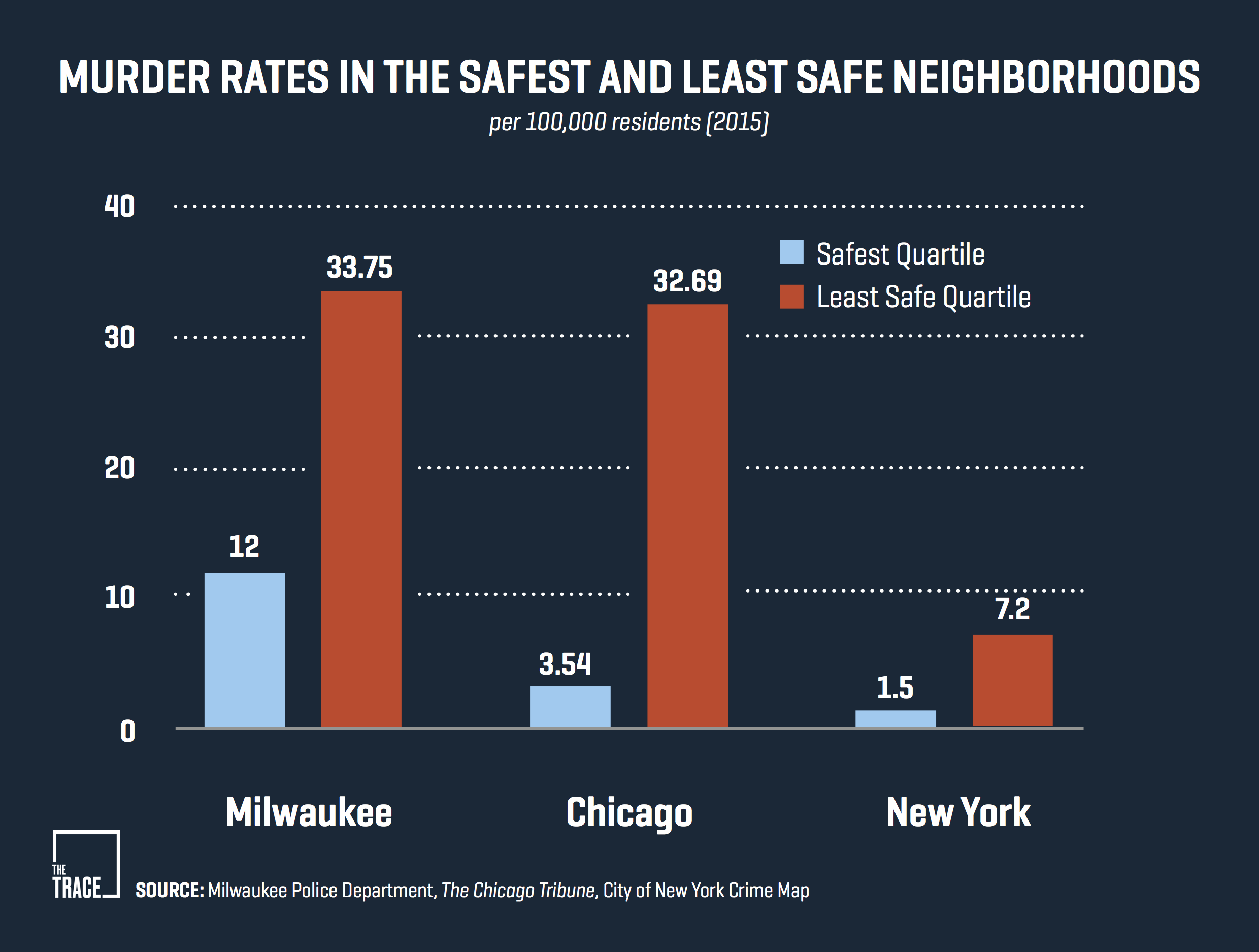

At a city level, there’s an easy answer. New York has fought back from a violent recent past to become among the safest big cities in the Western world; Chicago, as previously discussed, has made national and even international headlines for persistently high levels of gun crime. The difference can be boiled down to stark numbers: In 2015, there were 4.1 homicides per 100,000 New Yorkers, and 17.3 per 100,000 Chicagoans.

But those averages obscure a crucial fact: Just like income, education, and other metrics of social advantage, violent gun crime varies even more within American cities than between them.

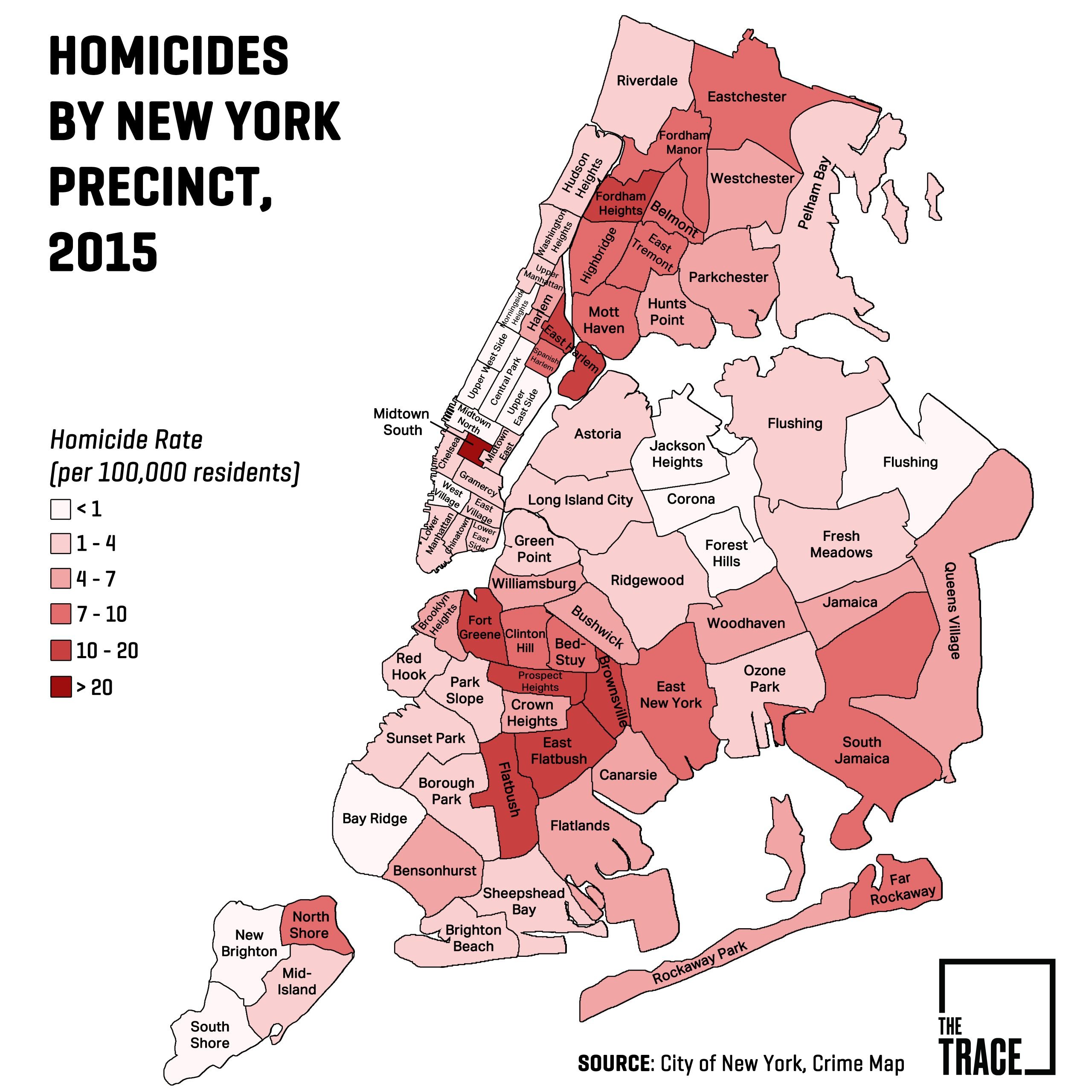

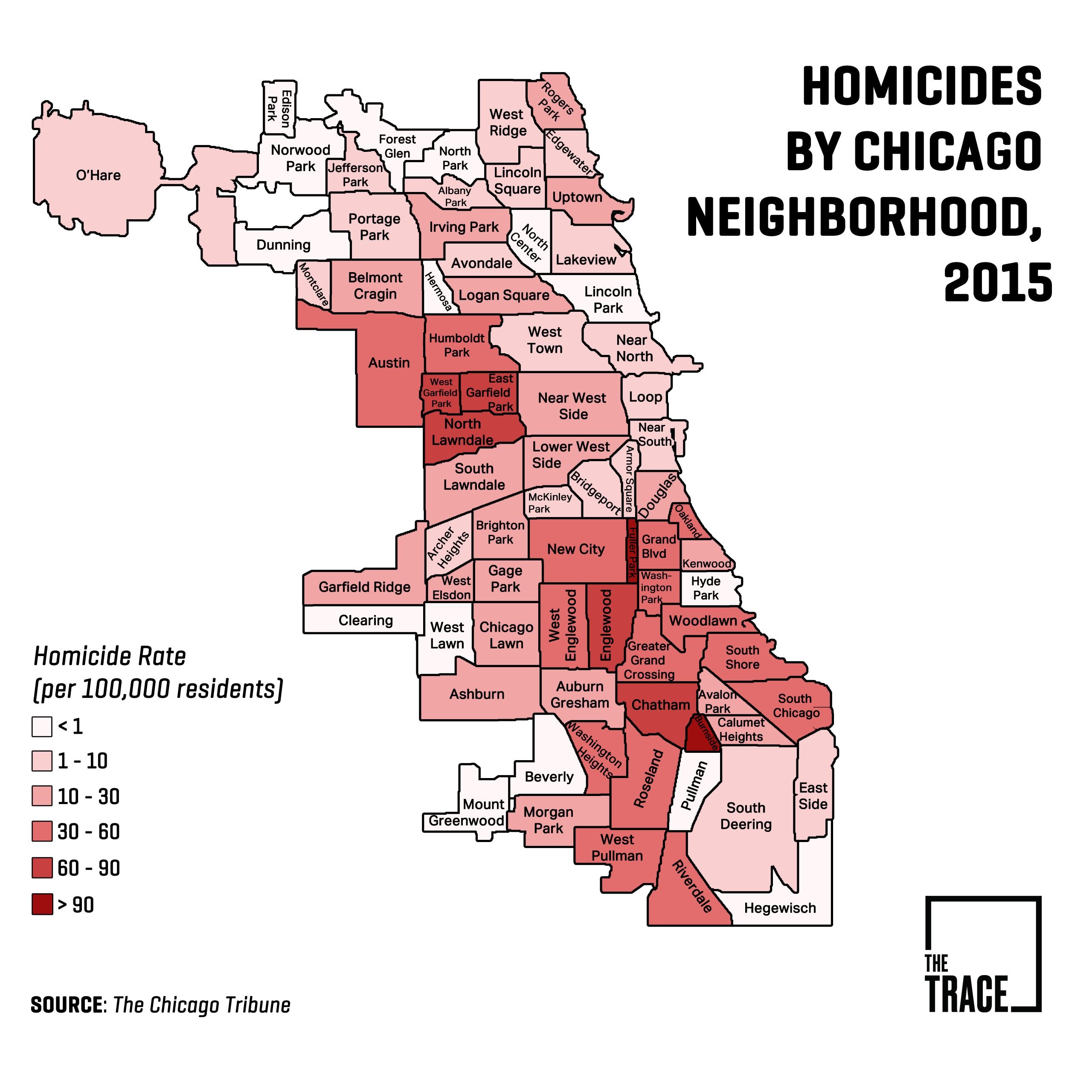

There are dozens of neighborhoods in both New York and Chicago where the homicide rate is near zero. There are also neighborhoods (many more in Chicago than in New York) where the homicide rate is much higher than the average.

In Brownsville, Brooklyn, the murder rate in 2015 was 16 per 100,000, or about four times the New York rate. That rate is similar to a bevy of Chicago neighborhoods, including Douglas, South Lawndale, and West Elsdon.

But in Chicago a murder rate of 16 is just below average.

Both New York and Chicago have safe and not-as-safe neighborhoods. Chicago’s homicide rate is so much higher than New York’s not simply because there are more high-crime neighborhoods in Chicago, but because Chicago’s high-crime neighborhoods are many times more violent than not-safe neighborhoods in New York. In two Chicago neighborhoods, Burnside and Fuller Park, the homicide rate eclipsed 100 per 100,000 residents last year, more than five times the Chicago average, and more than 25 times the typical New York neighborhood.

As with income and access to education, vast inequality is one of the most important features of American violent crime. That’s especially true because, again following the pattern of other kinds of advantage, relatively safe neighborhoods tend to cluster with other safe neighborhoods, and more violent neighborhoods with other violent neighborhoods, making it more likely that people spend much of their time in places that experience either far less, or far more, violent gun crime than their city’s overall numbers would suggest.

In Chicago, as in other cities where homicides are rising, one side of the divide is represented by communities that can nonetheless go a year, or years, without a fatal shooting. The other is comprised of neighborhoods that suffer violent crime at several times the pace of their city’s average rate — even where the city’s average is already alarmingly high. If East Garfield Park were an “average” neighborhood in Chicago, for instance, it would have had about three homicides last year among its 20,000 residents. Instead, it had 15.

Such disparities also belie the impression given by city rates that make a place, like New York, seem safer than others. Let’s look at Brownsville again: If the police precinct that includes the neighborhood were typical of New York, it also might have seen about three murders among its 86,000 residents; instead there were 14.

Turn to other cities, and the pattern holds. In 2014 (the most recent year available), Washington, D.C.’s homicide rate was nearly identical to Chicago’s, at 17.4 per 100,000 residents. But few of the city’s seven police districts look anything like that average: Their murder rates range from 1.1 in the Northeast’s First District, to 41.5 in Anacostia’s Seventh District.

The homicide rate in Milwaukee in 2015 was 23 per 100,000. But like with other cities, the average doesn’t say much about the relative risk of murder for most residents of the city. In the police district that includes downtown, the homicide rate was just two. In the bordering district to the north of downtown, the murder rate was 55, or 22.5 times as high.

From this perspective, America’s gun violence problem belongs to an archipelago of neighborhoods found in most metropolitan areas in the country, from New Orleans to Minneapolis, and from Los Angeles to Philadelphia.

Here it’s crucial to note that research strongly suggests that the likelihood of victimization by violent crime isn’t evenly distributed within violent neighborhoods, either: Yale professor Andrew Papachristos has found that being part of particular social networks can increase your chance of being the victim of a homicide by up to 900 percent above an already-high neighborhood average.

High levels of gun crime profoundly affect neighborhood residents whether or not they are a direct victim. Witnessing a shooting, or having a friend or loved one become a victim, can be deeply traumatic, leading to depression, anxiety, difficulty concentrating at school or work, and other issues. High crime rates can affect whether businesses are willing to locate near your home, reducing your access to important services like banking, and contributing to depopulation and abandonment. (In at least one case, violent crime convinced an urgent care clinic in North St. Louis to remain closed during on weekends.)

Nor are neighborhoods facing these issues randomly distributed: They are much more likely to be home to disproportionate numbers of people with low incomes and people who are black or brown. That racial and economic segregation play an important role in perpetuating deep social inequalities has been well-established. Directly and indirectly, violent crime is itself a crucial part of the basket of disadvantages that make living in a segregated neighborhood so costly.

A paradox of teasing out neighborhood-level crime numbers is that they make the differences between high- and low-crime cities more meaningful. High-crime neighborhoods in New York, Washington, D.C., and especially Chicago are significantly more dangerous than their surrounding cities.

Understanding this nuance perhaps could allow the public debate over crime policy and gun control to progress in a more constructive way. Polls show that even as the vast majority of Americans support basic measures like universal background checks, they don’t believe they will be effective in reducing shootings. With a better handle on the geographic contours of the problem, perhaps strategies oriented towards fixing the public safety crisis in these particular neighborhoods — like hot-spot policing — can take a more prominent place.

[Photo: Ralf-Finn Hestoft/Getty Images]