Gun-rights advocates are seeking to win new support for their agenda by promoting, with increasingly strident rhetoric, the notion that women are safest when they are armed.

“All of America’s women, you aren’t free if you aren’t free to defend yourself,” National Rifle Association Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre declared in a fiery speech in March. Marion Hammer, a former NRA president who wields tremendous political influence in Florida, accused opponents of a guns-on-campus bill of “engaging in a war on women” last August.

Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz has brought the notion into the 2016 campaign. “If you’re a single mom living in a tough neighborhood,” he said on “Good Morning America” recently, “the Second Amendment protects your right, that if someone comes through the window trying to harm your kids … You have a right to be armed to protect your family.”

Gun marketers, too, have pushed women to arm themselves. There are now whole stores set up to sell pink-hued firearms and accessories.

By at least one measure, the message seems to be persuasive: 56 percent of female gun owners believe that having a gun makes the home a safer place, according to a recent survey conducted by Marie Claire. (Among women in general, 20 percent hold that view.)

But the available evidence does not support the conclusion that guns offer women increased protection. Myriad studies show that the NRA and its allies grossly misrepresent the actual dangers women face. It is people they know, not strangers, who pose the greatest threat. There is also strong, data-based evidence that shows owning a gun, rather than making women safer, actually puts them at significantly greater risk of violent injury and death.

In some places and in some instances, women have, in fact, used guns to successfully defend themselves. But the case that gun rights advocates make when pitching guns as essential to women’s personal and family security goes beyond the anecdotal, leaning heavily on an oft-cited 1995 study by the Florida State University criminologist Gary Kleck — a study built on faulty research.

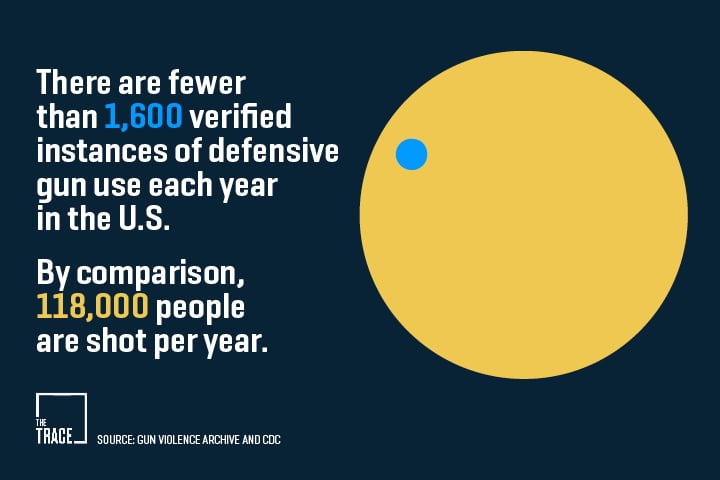

In his findings, Kleck estimated that women use guns to defend themselves 1.2 million times per year, and that 200,000 such defensive gun uses stopped sexual assaults. Those estimates have proved to be wildly inflated. Successful defensive gun use is, in fact, extremely rare among all people: There are fewer than 1,600 verified instances in the U.S. each year, according to the Gun Violence Archive. By comparison, annually, 118,000 people are injured, killed, or kill themselves with a gun.

Women who were victims of attempted or completed crimes used guns to defend themselves just 0.4 percent of the time, according to the National Crime Victimization Survey. (The survey uses a representative sample of 90,000 households in order to estimate national crime rates.) A Harvard study found that, of the more than 300 cases of sexual assault reported in the sample of NCVS data between 2007 and 2011, none were stopped by a firearm. Of the 1,119 sexual assaults reported in the NCVS from 1992 to 2001, a different study revealed that only a single case was stopped by defensive gun use. And, as we have shown in previous articles, even these numbers from the NCVS likely overestimate the true rate at which women protect themselves with firearms.

The evidence is clear: Women simply aren’t defending themselves with guns at a significant rate.

It’s possible that gun activists could use that fact as reason for getting more firearms into the hands and homes of more women. But here their argument hits its critical flaw: Every credible scientific study of women and guns in the last two decades strongly indicates that a firearm in a woman’s home is far more likely to be used against her or her family than to defend against an outside attacker. Increasing gun ownership by women would only heighten that risk.

The bottom-line statistic that most broadly assesses the relationship between women and firearms was determined by research conducted by the Department of Preventive Medicine at the University of Tennessee. That study, from 1997, concluded that the presence of a firearm in a woman’s home triples the odds that she will be killed.

Usually, the person using a gun against a woman — contrary to Ted Cruz’s assertions — is not a stranger, but someone she knows, frequently an intimate partner. As The Trace previously noted, an average of 554 American women are fatally shot by romantic partners every year. That works out to a domestic violence gun homicide with a female victim once every 16 hours.

According to another, older University of Tennessee study, the rate of women killed with a gun by their husband or an intimate partner is more than double the rate of women killed by strangers using guns, knives, or any other method. (Newer gun violence studies are scarce, at least partially due to resource shortfalls that researchers have faced since Congress curtailed federal funding for the subject in 1996.)

Domestic abuse is five times more likely to turn deadly if firearms are present in a home. A case-control study comparing women killed by an intimate partner to women who had been battered but not killed revealed that more than half of the homicide victims lived with a firearm in the home, while that was true for only 16 percent of women who were abused but survived.

Yet another study found that family and intimate assaults involving firearms were 12 times more likely to result in death than those using other weapons or bodily force.

Despite all the evidence, when given the opportunity to endorse gun violence prevention measures that would make women safer, the NRA consistently does the opposite, fighting to defeat legislation, for example, that would require people served with a restraining order — whether temporary or permanent — to surrender their firearms.

Such laws, which have been put in place in a handful of states, including California and Massachusetts, seek to remove guns from abusers at an especially volatile time: immediately after a restraining order is issued. A 2009 study published in the journal Injury Prevention found that domestic violence restraining orders that block access to firearms decreased intimate-partner homicide by 19 percent.

The NRA has also sought to keep open the “boyfriend loophole.” Under federal law, a person convicted on a misdemeanor domestic violence count of abusing a dating partner is not required to surrender his or her guns. (Some state laws have sought to eliminate this exception.)

The maintenance of this loophole means an estimated 50 percent of victims have no legal recourse to prevent their abuser from possessing a firearm. Convicted stalkers are also exempt from laws barring abusers from buying and keeping firearms — despite the fact that 76 percent of domestic homicide victims are stalked before they are killed.

But the NRA often has little use for empirical evidence that does not match its world view. Last year in Louisiana, the NRA argued that extending the definition of domestic abuse to women who were not married to their abusers would incentivize false claims of abuse. An NRA spokesperson claimed that the bill was “so overly broad that it could make a felon out of a girlfriend who pulls a cell phone from her boyfriend’s hand against his will.”

[Photo: Press Association via AP Images]