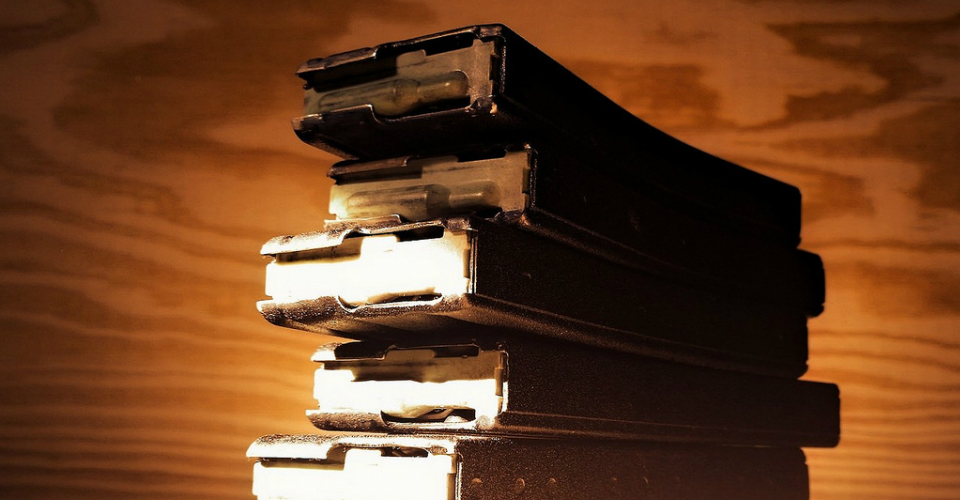

Los Angeles is considering a slate of new gun laws following a spate of mass shootings and federal inaction. The city’s main target: High-capacity magazines.

Mayor Eric Garcetti says he is eager to sign the proposal put forth this week by the City Council, which would ban gun magazines capable of holding more than 10 rounds within L.A. city limits. Anybody who already owns such a magazine would be forced to remove them from the city or surrender them to the LAPD to be destroyed.

It’s an unusually strict law, but not a new idea. The argument over high-capacity magazines is among the most contentious flash points in the gun control debate: While gun rights advocates say the restrictions only punish lawful gun owners, gun violence prevention experts argue that more bullets between reloads can result in greater body counts.

In a recent Newsweek cover story, Kurt Eichenwald writes, “Why would any gun enthusiast need 100 rounds? James Holmes can tell you.” Holmes used a 100-round magazine to kill 12 people and injure 70 others in his rampage in an Aurora, Colorado, movie theater. In Tuscon, Arizona, Jared Loughner killed six people with bullets fed from a 33-round magazine. According to a tally by the Violence Policy Center, high-capacity magazines have been involved in at least 45 mass shootings since 1994.

Measures to restrict magazine sizes, consequently, often follow high-profile gun massacres. Colorado banned magazines larger than 15 rounds following Holmes’s Aurora massacre, prompting a quick backlash. Sheriffs sued the state, and a new Republican majority in the state legislature has pushed hard for repeal.

To better understand the debate over magazine capacity limits, it’s helpful to go back to basics:

Who came up with the idea for gun magazine capacity limits?

The answer might not be what you’d expect. Credit for first leading the charge against high-capacity magazines is often given to gun company executive William Ruger.

Following a series of high-profile incidents during the ’80s — a firefight in Miami, Florida, where criminals outgunned FBI agents; a Stockton, California, schoolyard shooting committed with an AK-47; the rise of well-armed urban gangs in the wake of the crack epidemic — Ruger sent model legislation to members of Congress urging a ban on magazines holding more than 10 rifle or shotgun rounds or 15 pistol rounds. The proposal was seen as an alternative to outright bans on certain classes of guns and found support with several gun-industry trade groups.

The model legislation helped inform language that would find its way into the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994. The law prohibited “large capacity” magazines, which it defined as those capable of holding more than 10 rounds, though the possession or sale of magazines manufactured before the bill’s passage were not not made illegal.

That national ban expired through a sunset provision in 2004, but various states and municipalities keep laws banning the possession, sale, or manufacture of such magazines on the books.

What’s the argument in favor of the policies?

Gun violence prevention advocates claim high-capacity magazines increase mass lethality without clear hunting or self-defense applications.

In contrast to bans on so-called military-style assault weapons in states like New York, bans on the components go after more than just firearm aesthetics: Jared Loughner’s rampage was only stopped when a civilian tackled him as he was reloading after exhausting his pistol’s extended magazine, and many wondered if fewer people would have been killed or injured if he’d been forced to pause earlier.

The bans also stand up better in court. Even after the Supreme Court struck down bans on handguns, it has thus far allowed bans on high capacity magazines.

What’s the opposition?

Like most gun policy debates, the one over magazine sizes inspires some amount of Second Amendment absolutism. More nuanced opposition focuses on just how the law defines “high capacity”: It’s usually only the most rigid gun-rights advocates who defend 100-round drums, but most bans preclude far smaller capacities.

New York’s SAFE Act banned magazines carrying more than seven rounds. But few companies manufacture magazines that small. Soon after the act’s passage, Governor Andrew Cuomo called for a fix that would allow more common 10-round magazines, so long as they were only loaded with seven bullets. Critics of the restrictions are not mollified by such work-arounds. They argue that even police trained in how to handle shooting situations require many shots to defend themselves, so magazines that small could negate a gun’s self-defense purpose, which was enshrined by the Supreme Court in its decision striking down handgun bans.

Are bans on high-capacity magazines effective?

At the time of the 1994 ban, a central question was whether the many high-capacity magazines already in circulation might constrain the law’s effectiveness. Glock notoriously took advantage of the provision in the law that only restricted large magazines manufactured after the ban went into effect, stockpiling its existing high-capacity magazines in order to sell them for a premium once the law took effect.

Another complication: Certain magazines designed to hold small numbers of high-caliber rounds can be loaded with more bullets of smaller caliber and evade laws in the process.

The Alexander Arms’s Beowulf magazine feeds four .50 rounds into an AR-15 rifle, but it can also hold more than twice that number of of slimmer .223 or 5.56 ammunition. In Canada, which has a five-round limit for rifle magazines, the fact that the Beowulf magazine was intended for a smaller number of large rounds has kept it legal. More recently, 3-D printed high-capacity magazines have provided a new way to evade restrictions.

But despite those challenges, a Washington Post analysis suggests that the federal ban was effective at limiting criminals’ access to these components. It took time, though: Data provided by the Virginia State Police showed that the size of magazines recovered from criminals steadily dwindled, falling from 944 in 1997 to 452 in 2004 — an all-time low. After the ban expired that year, magazine sizes in Virginia crime guns started climbing back up, jumping to 986 by 2009.

[Photo: Flickr user Cerebralzero]