All eyes are on the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), after Director James Comey admitted that a “cascade of errors” allowed alleged Charleston church shooter Dylann Roof to purchase a firearm. But as details continue to emerge about how Roof was able to buy a gun he should have been barred from purchasing, one crucial question remains unanswered: What happened to the still-incomplete background check after the sale went through?

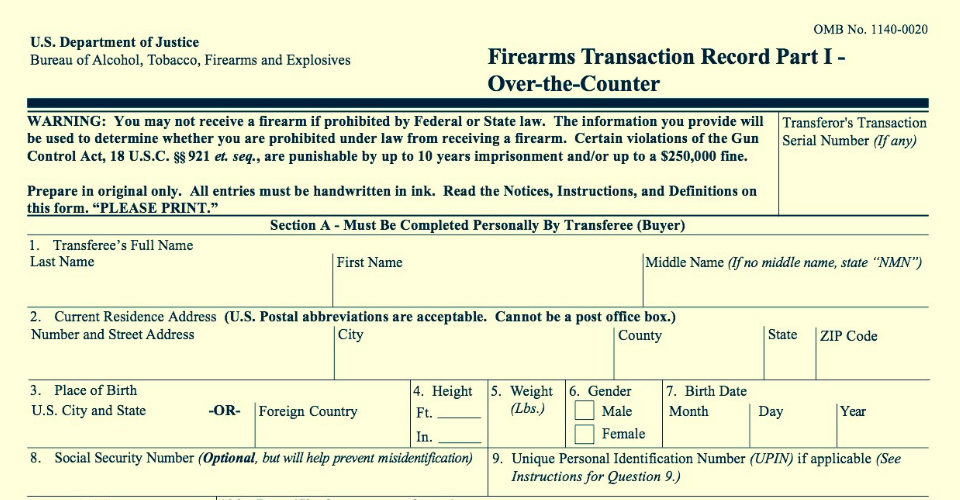

Under federal law, when the NICS takes more than three business days to process a background check, a gun seller can legally complete a purchase without FBI approval. This is called a default proceed. Due to compounding clerical errors, a NICS examiner was unable to access Roof’s arrest record in the allotted time, and the West Columbia, South Carolina, gun shop lawfully went ahead with the sale.

When a background check runs past the three-business-day deadline, the NICS examiner tasked with the case will still attempt to make the final determination on the purchaser and has up to 90 days to reach a conclusion. The FBI declined to answer questions from The Trace about the ultimate outcome of Roof’s background check.

Why does all this matter? Because if a NICS examiner did eventually gain access to Roof’s arrest record — which included a disqualifying confession to drug possession — the agency’s next step should have been to alert Shooter’s Choice gun store of his prohibited status. After confirming that the purchase had gone ahead on a default proceed, the FBI would have then sent a “retrieval referral” to the ATF. The agency, in tandem with local law enforcement, is then supposed to confiscate the weapon. Reports peg the day Roof got his gun as April 16 (he’d first tried to buy it on April 11, a Saturday). The Emanuel AME shooting was on June 17 — well within the 90-day window for reaching resolution on his background check. But again, what we don’t know is what was happening with the case during that time.

Retrieval orders issued by the FBI after default proceeds are a relatively rare occurrence. A NICS operations report from 2000 noted that of more than 45,000 default proceeds issued that year, approximately 5,000 had to be rescinded with a retrieval referral (that year, NICS’s second full year in operation, saw the highest number of retrieval referrals on record). Agency data from 2001 to 2014 places the average number of retrieval orders issued to the ATF at around 3,000 per year. The FBI has not posted the number of default proceeds for those same years, so it’s not possible to tell what share of sales to prohibited purchasers result in efforts to track down those guns.

Even when we know retrieval referrals were issued, it’s not clear how often the ATF manages to follow through on collecting the ill-gotten firearm. The process can be complicated by local staffing issues and rivalries between different levels of law enforcement, as was the case at the ATF’s Northern Nevada office. In November 2012, the Reno Gazette-Journal reported that a dispute between the local ATF branch and the federal prosecutor’s office was followed by the abrupt transfer of the agents who would have performed the retrievals of the 36 weapons sold to individuals in the area who ultimately failed a state background check. Officials knew the guns were out there, but no one was sent to get ahold of them.

As of this writing, the ATF had not provided the Trace with information on how many retrievals the agency successfully completes each year.

[Photo: atf.gov]