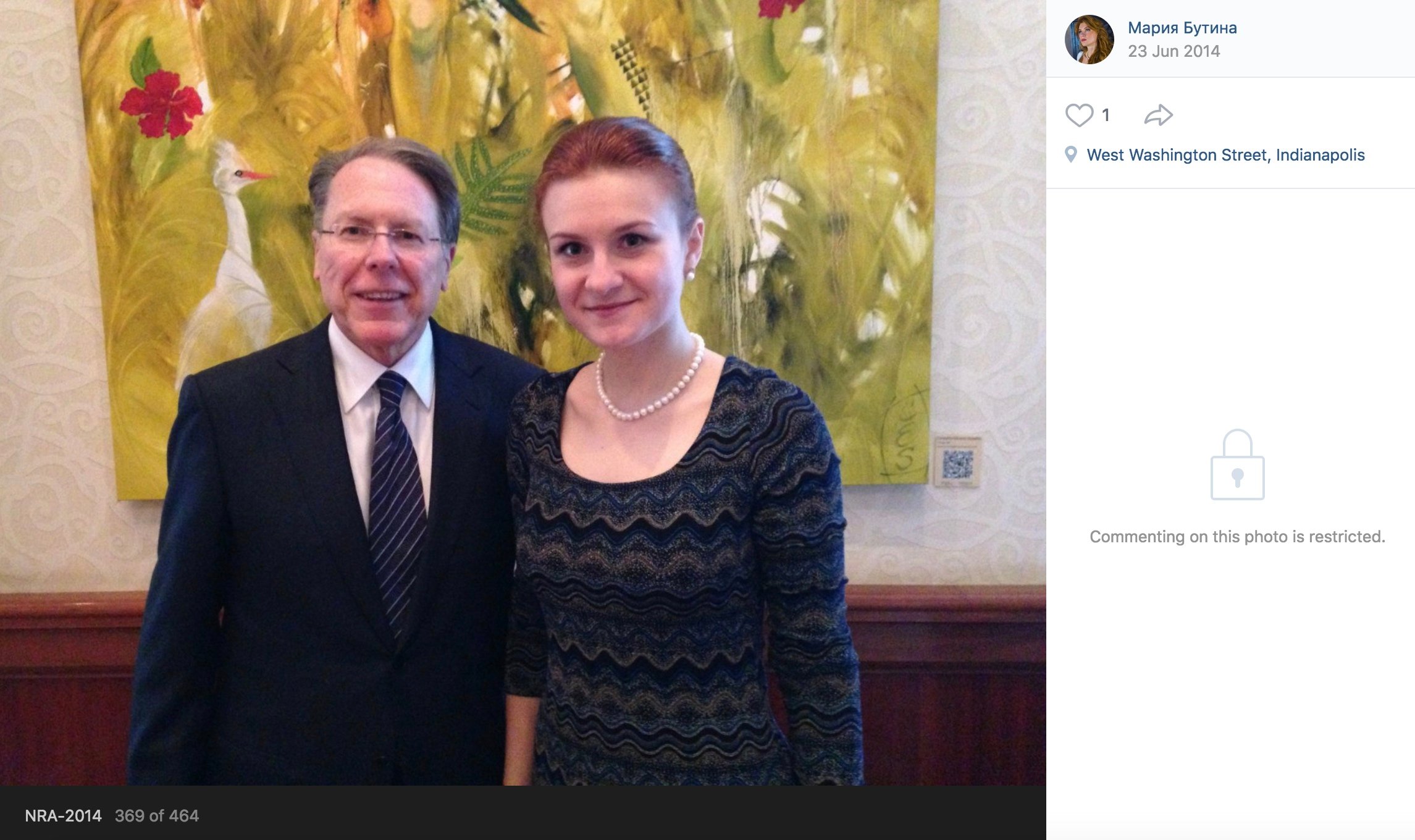

The federal indictment of the accused Kremlin spy Maria Butina lays out how the 29-year-old operative infiltrated groups like the National Rifle Association in an attempt to push U.S. politics in a more Russia-friendly direction. American conservatives and Republicans, she told an American associate in an exchange recounted in an FBI affidavit, have been “traditionally associated with negative and aggressive foreign policy, especially with regards to Russia.” Her mission was to change that attitude.

We don’t yet know exactly what Butina said to the many prominent Republican politicians and NRA leaders she is known to have met. But there are some clues that gun politics were central to her approach. The Washington Post reported that she brought up gun rights before asking to exchange business cards and contact information.

In a handful of appearances in conservative media, Butina spun a common cause between American and Russian right-wingers, one based on shared ideas of gun rights. At the core of her influence campaign was the ideology of armed self-defense.

Butina touted her work as the founder of Right to Bear Arms, a Russian gun rights group, which she launched in 2011. Speaking with the conservative writer Eric Metaxas in 2015, Butina traced her embrace of gun rights to her rural upbringing:

I was born in Siberia, and my father was a hunter. In Siberia, lots of people own guns. It’s a question of survival. It’s not just hunting — there are wild animals … wolves.

With Right to Bear Arms, as she shared with longtime right-wing activist Grover Norquist in a 2016 podcast interview, when Norquist was still on the NRA’s board of directors, her goal was to ultimately create a Russian legal right to lethal self-defense. That right does not exist in that country’s legal code:

In Russia, very few people have guns and it’s a very hard procedure [to get one]. Mostly it’s shotguns for hunting, a few rifles, and so it’s very hard to get. You have to go to the police to get special permission. … We don’t have pistols, we don’t have revolvers. This is one of the points of our organization to fight. We do have special guns for concealed carry, believe it or not, with rubber bullets. This cannot kill the criminal … It’s ineffective. Our police use real pistols. Why do you give to the citizens different guns? Do they meet different criminals?

But as Butina explained, many of her fellow Russians weren’t yet ready to be “good guys with guns.”

Russians, especially those over 55 years, don’t want to defend themselves at all. They believe that if they become a pure victim and do nothing the criminal will feel sorry about this. No! Please watch all movies, thrillers and so on. It never works. If you give up and tell all the truth, you will be killed.

Butina added that in her homeland she had some early success working with her longtime boss and associate, Alexander Torshin, who had served in the Russian legislature and became a life member of the NRA. With their encouragement, she said, the legislature had passed a law that would create a Russian version of “castle doctrine,” codifying the idea that people can respond to threats with deadly force in their own home. President Vladimir Putin did not ultimately sign the measure into law, yet she declared the effort a victory:

For our group it was a huge success. A couple of years before, it was thought only crazy people wanted guns. [After the proposal was introduced] It became one of the most discussed questions in Russia.

Finally, borrowing another theme from American gun proponents, she also connected armed self-defense to a deeper national heritage.

[Designer of the AK-47 rifle] Mikhail Kalashnikov told young Russian people, if you use a gun, the number one purpose is self-defense. He was NRA life member. He visited America several times, and his dream was that we will have in Russia an organization like the NRA…he promotes gun rights inside Russian government, telling them, ‘Look guys, this is not dangerous. You can give people the right to defend themselves, they feel more happier…when they are waiting for police, they try to make the government responsible for them to defend them, but the government cannot.’

In reality, Russians had few individual rights. But Butina argued that their national heroes wanted them to own and use firearms freely.

Butina’s approach struck American conservative figures as novel and interesting. As Norquist said when he introduced the interview with her, “I’m a little bit surprised to learn people have any guns in Russia or that there’s a group that’s allowed to campaign for what we would call Second Amendment rights. I guess it’s probably not called Second Amendment rights in Russia.”